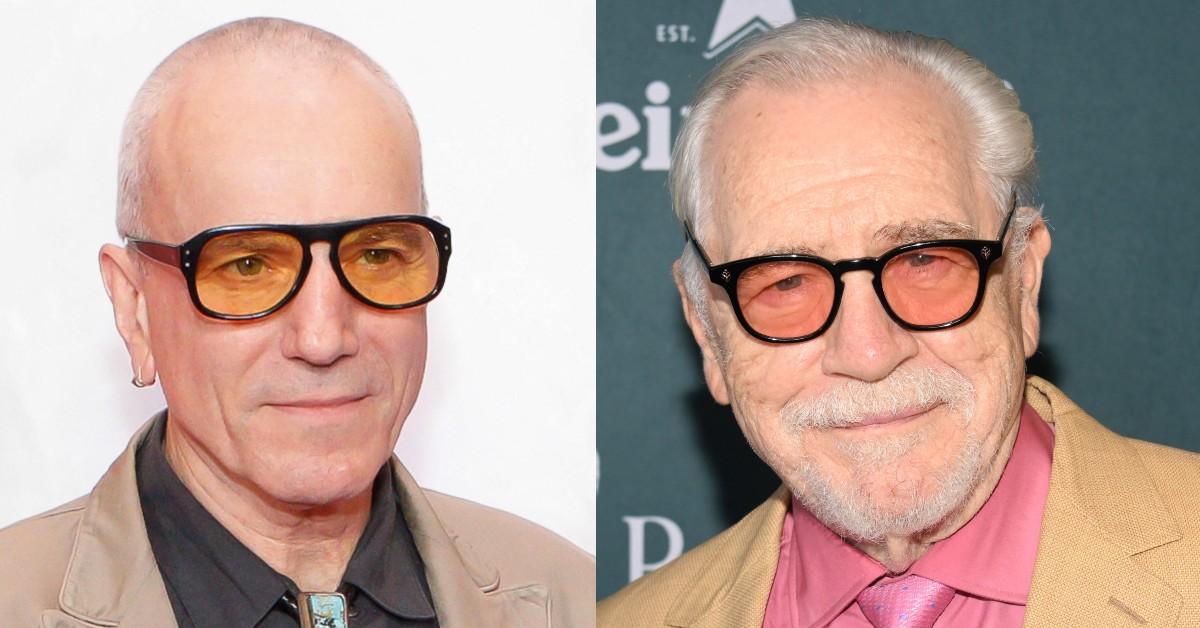

Daniel Day-Lewis has reignited Hollywood’s fiercest acting debate – method or madness – after clashing with Brian Cox over what the veteran actor called the “lunacy” of method acting.

But RadarOnline.com can reveal that for Day-Lewis, 68, it’s not insanity but devotion – while for Cox, it represents self-indulgence.

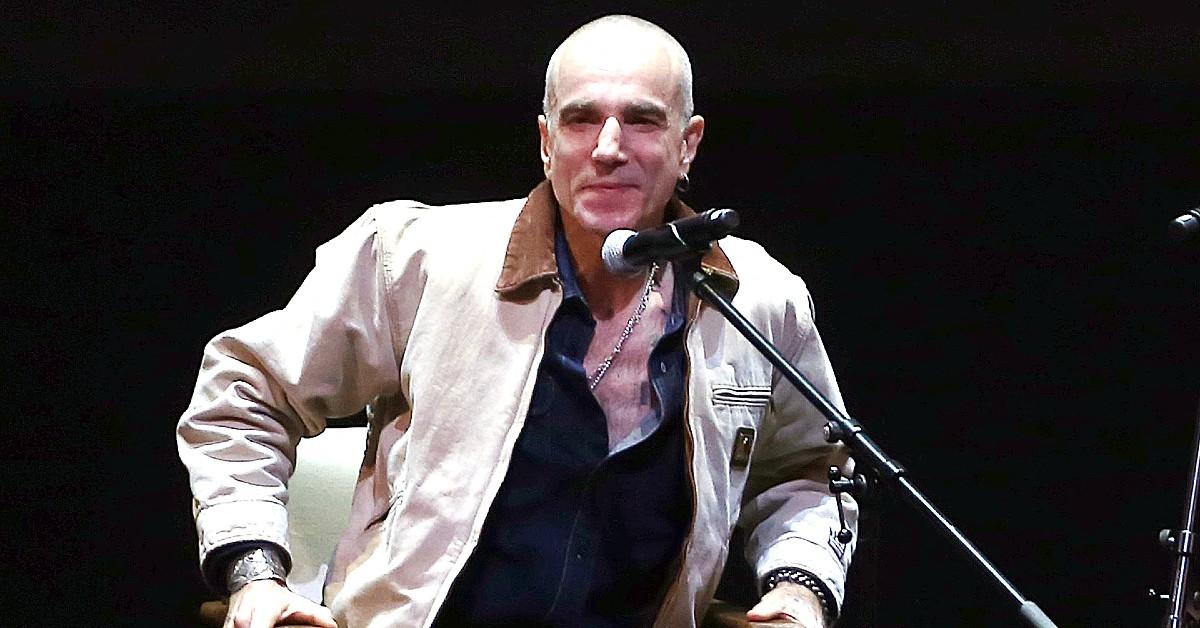

Day-Lewis’ Philosophy on Acting

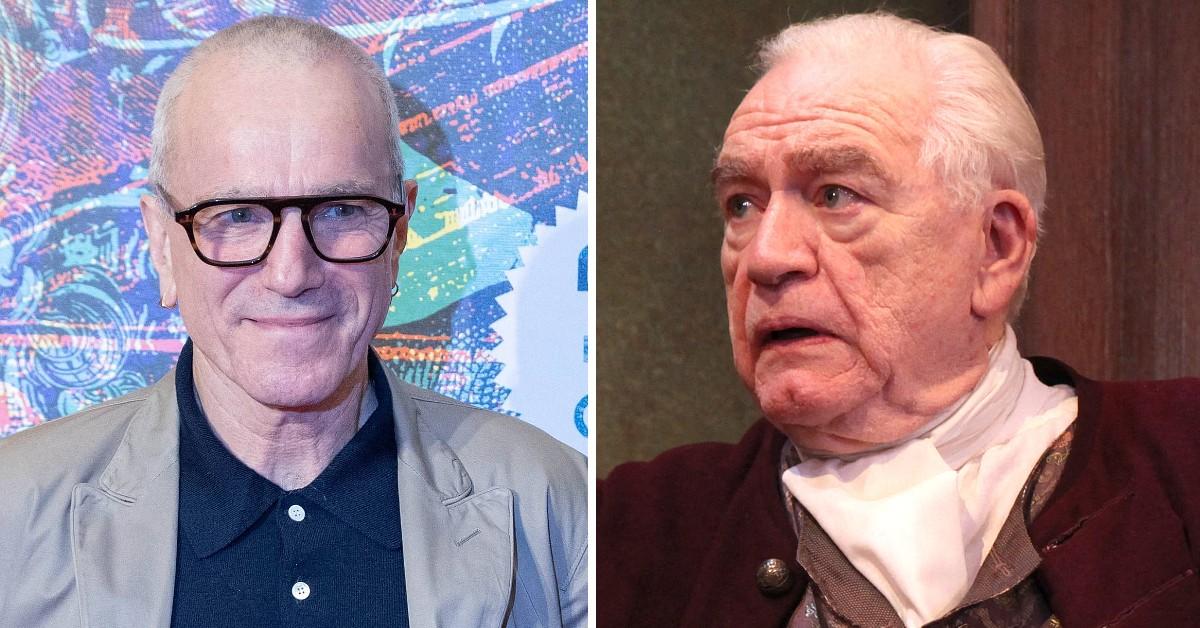

Daniel Day-Lewis immersed himself fully in character during filming.

Three-time Oscar winner Day-Lewis, who is returning to screens this year in his son’s movie Anemone, defended his lifelong commitment to the craft in The Big Issue, insisting critics “don’t understand” what method acting truly means.

He said: “I just don’t like it being misrepresented to the extent it has been. I can’t think of a single commentator who’s gobbed off about the method that has any understanding of how it works. They focus on, ‘Oh, he lived in a jail cell for six months.’ Those are the least important details.”

Day-Lewis added: “It p—– me off, this whole, ‘Oh, he went full method’ thing. What the f—, you know? Because it’s invariably attached to the idea of some kind of lunacy.”

A Hollywood insider said: “Daniel doesn’t see it as madness – he sees it as truth. Every role he’s taken, he’s lived it. He’s not pretending, he’s becoming. That’s the difference.”

Day-Lewis’ journey through cinema is a history of extremes.

In My Beautiful Laundrette (1985), he transformed into working-class punk Johnny, immersing himself in London’s Vauxhall neighborhood and adopting a South London accent that never slipped, on or off set.

Legendary Transformations

Day-Lewis pushed boundaries while preparing for a tense confrontation.

Three years later, in The Unbearable Lightness of Being (1988), he played Czech surgeon Tomas and learned Czech to capture the soul of Kundera’s conflicted protagonist.

But it was My Left Foot (1989) that established his legend – as he remained in a wheelchair for the entire shoot as Christy Brown, the Irish poet with cerebral palsy, and even being spoon-fed by the crew.

The effort broke two of his ribs but won him his first Oscar.

For The Last of the Mohicans (1992), he trained for months in the wilderness, learning to hunt, track and build canoes by hand.

He carried his flintlock rifle everywhere – even to Christmas dinner – and once admitted: “I find it difficult to be in rooms now for long periods of time.”

Extreme Immersion in Roles

Cox studied Day-Lewis’ performance before delivering his own lines.

His portrayal of wrongly imprisoned Gerry Conlon in In the Name of the Father (1993) saw him lose 50 pounds, sleep in a cell for three days and be repeatedly doused with cold water to mimic interrogation.

For The Crucible (1996), he built his own 17th-century cabin, lived without electricity, and rode horses to set, rejecting modern transport.

And for his role in The Boxer (1997), he trained for 18 months under world champion Barry McGuigan, breaking his nose in the process.

Then came Gangs of New York (2002), where he learned butchery, wore authentic period clothing in freezing conditions, and caught pneumonia – refusing antibiotics.

Precision and Discipline

Day-Lewis consulted with the director to perfect every moment while filming.

Even when roles demanded refinement, his preparation was exhaustive. In Nine (2009), he spent five hours a day rehearsing singing and dancing in character as Italian director Guido Contini.

For Lincoln (2012), he lived entirely as the president, speaking only in Abraham Lincoln’s Kentucky accent and insisting on being addressed as “Mr. President.”

His turn in Phantom Thread (2017) as fashion designer Reynolds Woodcock showed a quieter kind of “madness” – apprenticing under Marc Happel, head of costume at the New York City Ballet and handcrafting a couture gown for his wife, Rebecca Miller.

Now, in the newly released Anemone, Day-Lewis returns after an eight-year hiatus to play a reclusive ex-soldier haunted by his past in Northern Ireland.

Surprisingly, his only preparation was mastering a Sheffield accent.

One crew member said: “He’s older now – maybe calmer – but it’s still all-consuming. Even when he’s doing less, he’s doing more than anyone else.”