When Yorgos Lanthimos first read the script that would become Bugonia, he knew almost instantly that he was about to do two things he had never attempted before in his acclaimed career: He would direct a film he hadn’t closely developed himself, and he would tackle a story more directly about the present-day state of the world than anything in his diverse but beguilingly abstracted previous features.

“Up until this point, I’d read scripts, but I’ve never been so excited immediately afterward that I would say, ‘This is almost ready for me to make just as it is,’ ” Lanthimos recalls. “To be handed something that was already so great was a tremendous gift.”

Within minutes of completing the script, Lanthimos sent it to his de facto muse and star of his previous three features, Emma Stone.

“I read it that same day, and from then on, we were like, let’s do this,” Stone says. “It was really crazy for me because ever since The Favourite, I’ve seen the projects we’ve done together in very different states of being, where they take years to develop. This was the first time we received a script and were like, ‘Whoa, let’s go make this right away,’ and it basically doesn’t require any process.”

The film is a loose remake of the 2003 South Korean black comedy horror thriller Save the Green Planet! — a wildly inventive blend of genres and ideas that tells the story of a young man who kidnaps and tortures a corporate CEO, believing the exec is an alien in disguise bent on bringing destruction to Earth. The film was the visionary feature debut of Jang Joon-hwan, a university classmate and close early collaborator of Bong Joon Ho. But while Bong would go on to Oscar glory, Jang’s career was derailed when Save the Green Planet! flopped and quickly disappeared from cinemas. Despite the now-undeniable brilliance of his debut, Jang wouldn’t make another film for more than a decade.

“Cinephiles in Korea now call it ‘the cursed masterpiece,’ ” says Jerry Ko, head of global film at CJ ENM, which produced the original. Having noticed the growing traction of offbeat, high-concept moviemaking from A24 and Neon in the U.S. market throughout the late 2010s, Ko began to see potential in a possible remake. “It felt like maybe it was time to lift the curse,” he says.

The CJ development team’s hunt for a potential U.S. producing partner ended nearly as soon as it began. Just as they were getting started in late 2018, they noticed an announcement online for a retrospective screening of Save the Green Planet! at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art curated by Ari Aster, who was billed as a devoted fan. After a few phone calls, Aster and Lars Knudsen boarded the remake as producers under their Square Peg banner. The duo then brought on board Will Tracy, fresh from the highly decorated Succession writers room, to pen an English-language screenplay.

Despite its distant origins, Bugonia would prove to be of a piece with the Lanthimosian extended universe.

“Without intending to write a Yorgos-like film, I think it certainly ended up being very much within his wheelhouse,” Tracy says.

The writer watched the Korean original just once and then began drafting the remake from his Brooklyn apartment in early 2020, just as New York entered its first full COVID lockdown. In only three weeks, he had a full script.

Looking back on the process, Tracy says, “I do think, atmospherically, the experience of being locked down — of being confused, paranoid and not quite knowing what information to trust, not quite having a full grip on reality — all of that was probably to the script’s benefit.”

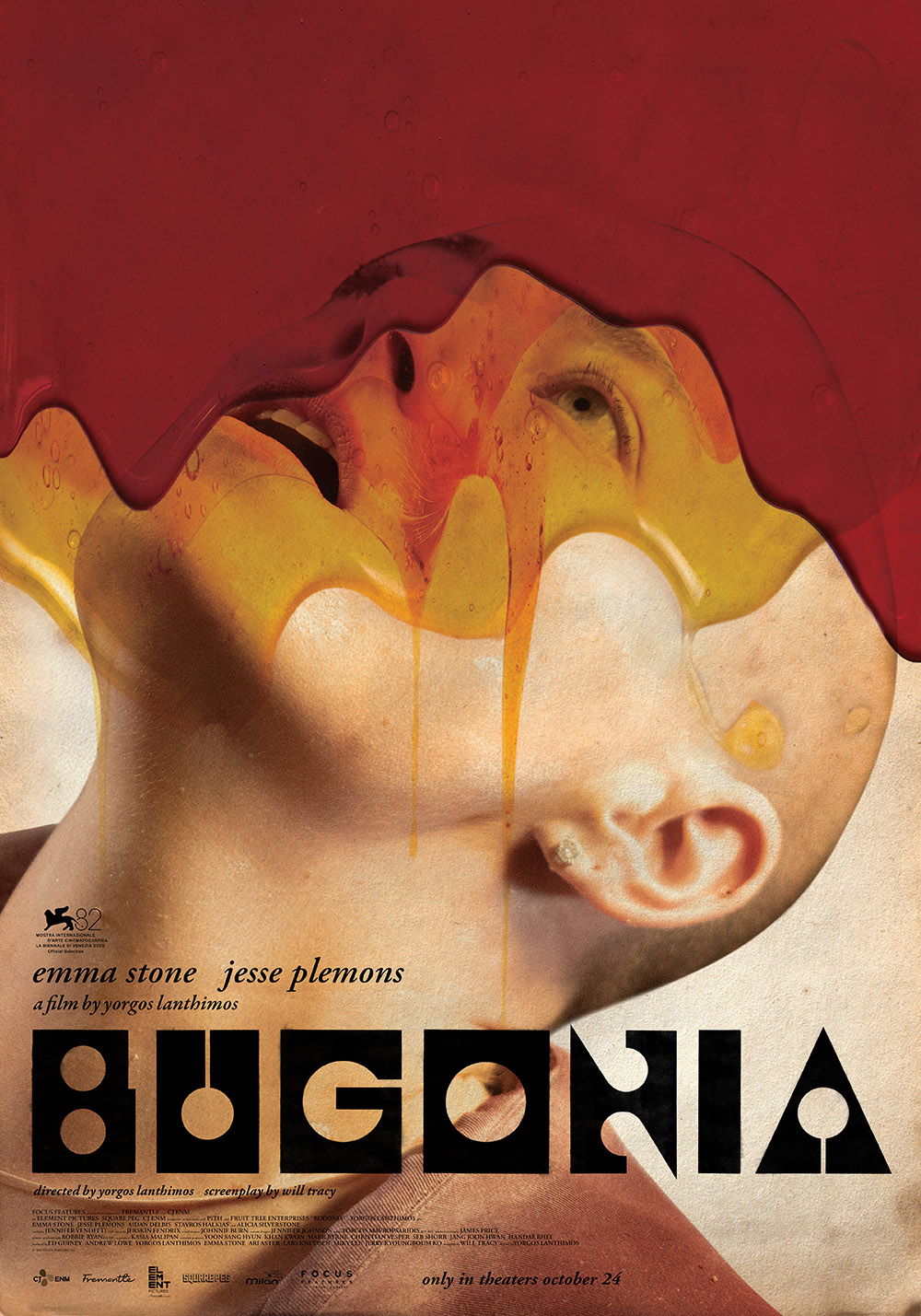

Jesse Plemons stars as Teddy, a deeply troubled beekeeper and conspiracist who hides and broods in a ramshackle Southern home with his gentle but pliant cousin Don (played by Aidan Delbis), believing that aliens from the Andromedan galaxy have infiltrated Earth and are slowly poisoning the planet. The hapless duo proceeds to kidnap Michelle Fuller (Stone), the coolly accomplished CEO of a drug company and pesticide conglomerate, who Teddy believes is one of the alien leaders in disguise. Much of the film’s drama then ensues inside Teddy and Don’s basement like a pseudo chamber piece as captor and captive face off in a battle of wits, logic and strange faith that blurs the lines between divisive politics, conspiracy and cosmic truth.

“Yorgos and Will really pulled off a magic trick,” says Plemons. “You have two characters with totally opposing beliefs — and my character, Teddy, is preaching his beliefs nonstop through the whole movie — but the film itself somehow doesn’t feel preachy and leaves it all to the viewer to decide. That was very appealing to me as a performer.”

Most of Bugonia was shot in the U.K., a short distance outside London, with a few exterior shoots in Georgia. Because so much of the film is set within a single location — Teddy and Don’s house — production designer James Price (Poor Things, The Iron Claw) pitched Lanthimos on building a fully functional home within a real British landscape, styled with telephone poles and other details to resemble the American South. He had initially envisioned shooting the basement scenes on a soundstage, but the director urged him to go further by constructing an authentic American-style basement beneath the house. The set decorators then exhaustively researched Americana interiors and detritus.

“It was all so detailed and such an amazing external picture of Teddy’s mind and the chaos going on inside him,” says Plemons. “Walking around that space was incredibly helpful to me.”

Adds Price: “It’s the only set I’ve ever felt emotional about destroying after we were done because it transcended a set. For me, it was a real place and a real home.”

Because so much of the film would be shot in such close interiors, Lanthimos and his director of photography, Robbie Ryan, sought to build on their experiments with The Favourite and PoorThings by using a film format that could lend their images richness and grandeur despite the confines. They had looked into using the now-in-vogue 1950s VistaVision format on Poor Things, but the retro cameras generate considerable noise — “Like a rickety old sewing machine,” says Ryan — so they were only able to employ it for one brief sequence that contained no dialogue. In the intervening years, however, advances in sound design had made it possible to digitally remove the cameras’ noise from even the quietest of scenes.

“When we realized it could be possible, Yorgos decided to fully commit — to shoot the whole thing, to the extent possible, on VistaVision,” explains Ryan. “The cameras are fragile and cumbersome — about 200 pounds — but it was really exciting because the images were just perfect.”

Much will soon be made of the movie’s epic, final-act twist, but despite such swerves, the film maintains its utter ambiguity to the end, giving heart to the lostness that so many across ideological spectrums now feel.

“In the four years since I first read the script, it feels like the film has only become more and more relevant — somewhat unintentionally — as we continue to push humanity toward the edge,” says Lanthimos.

“For me, I cry through the final moments of the film every time because I either feel hopeful or hopeless, depending on my mood,” says Stone. “It’s kind of crazy to end on such a strong final note that you can interpret in such opposite ways.”

Adds Plemons: “I held a screening in L.A. and invited a bunch of my friends, and they all came over to the house afterward. We had such interesting, surprising conversations that night. That’s what I hope it does for other people too.”

This story appeared in the Nov. 5 issue of The Hollywood Reporter magazine. Click here to subscribe.