In 1998 I was an aspiring screenwriter living in a small apartment in Hollywood. The building was across the street from a liquor store with a red neon sign that would blink on and off, reflecting on me in what I imagined to be a film noir-ish way as I sat at the computer, channeling my inner Bukowski — only instead of drinking cheap wine and writing poems about the struggle of the working class, I was smoking weed and eating takeout Chinese food while writing a screenplay about two dudes who smoked weed and ate takeout Chinese food.

The idea was to channel the Marx Brothers through the filter of Cheech and Chong, presented via the one-long-crazy-night movie paradigm. It was full of things that made the 25-year-old me laugh: fake rap videos, dogs getting stoned and large-breasted aliens. This goofy premise would eventually become an actual script, which I passed along to my TV agent after a writing credit on the first season of South Park landed me a job on the writing staff of That ‘70s Show. I sent the script over on a Friday, and on Monday I got a call from someone at the agency who introduced himself as my new feature film agent. He said he loved the script and had no doubt it would sell. For some reason I believed him.

Back then in that tiny apartment, however, it was just an idea for a silly, funny, teenage-demographic skewing movie. Lucky for me, the tail end of the 20th century was a good time to be a screenwriter writing a silly, funny, teenage-demographic skewing movie. At that time, producers and studios were hungry to produce cheap, broad comedies that would appeal to teenagers with disposable income who were eager to spend it at movie theaters. The late 1990s-early 2000s was a boom time for comedy at the box office in general. Movies like Meet the Parents and Scary Movie were making bank, stars like Adam Sandler and Jim Carrey were in high demand to headline comedy features, and screenwriters had plenty of opportunities to pitch the next high concept comedy, laden with memorable physical comedy set pieces (hello sperm hair gel), generating profits at the box office and then making another killing in the secondary DVD and VOD markets. The comedy feature market was so hot that a young screenwriter who had just sold a spec that got him a meeting with the Farrelly brothers would have been motivated to drive from Studio City to Santa Monica on the shoulder of the 405 during rush hour to get there on time (I still can’t believe I didn’t get a ticket).

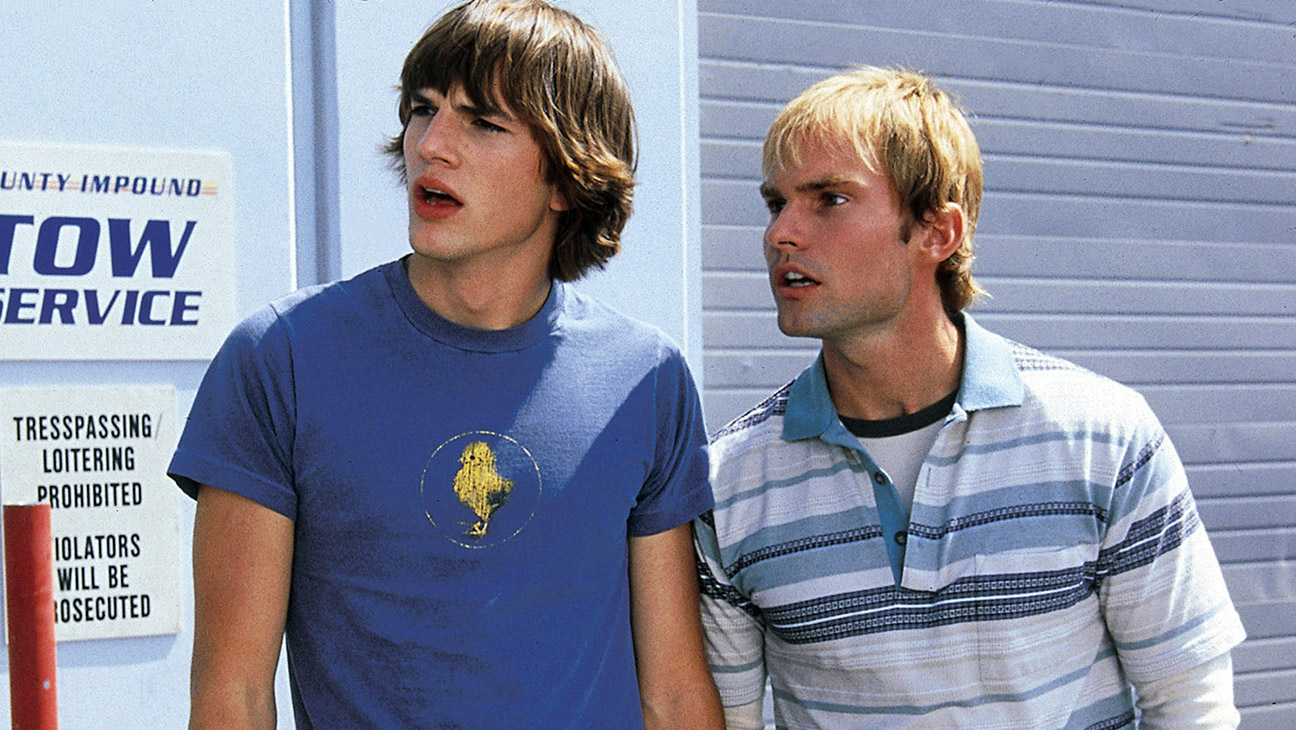

Dude, Where’s My Car? was released 25 years ago, on Dec. 15, 2000. It did better than expected at the box office, the title became a verbal meme we still refer to and a non-zero percentage of people walking around today have matching “dude” / “sweet” tattoos as a result. The movie starred two young, talented actors, Ashton Kutcher and Seann William Scott, launching them further into already successful careers. It made its production costs back the first weekend, and ended up being solidly profitable. Not exactly a smash hit, but certainly a success. And like all movies that get produced in this town, it was a long, bumpy path to the box office, with many hoops to jump through and pitfalls to avoid.

After the script sold I sat down for my first meeting with the producer who spearheaded the purchase, where I got a note I could never have anticipated getting: We need a third dude. So I spent six months writing drafts of the script as an homage to ’80s teen comedies, where the two dudes became secondary characters to the main character, an Anthony Michael Hall type whose girlfriend dumped him and who enlists the dudes to help win her back. Eventually another producer came onto the project and we went back to the original script, and then a wonderfully talented and collaborative director, Danny Leiner (RIP), came on board. The project gained momentum and as it hurtled towards a start date, the producers reached out to ask me about this Ashton guy I was working with. Was he funny? Was he a good actor? Did I think was right for the role? Hilarious, totally and absolutely were my replies. Then Seann, who was in the process of experiencing how the role of Stifler in American Pie would completely change his life, came on board, and we had the perfect dudes.

We shot the movie during a hiatus between seasons of That ‘70s Show when Ashton was available, which meant I was available too. It’s not often that the screenwriter of a movie is welcome on set, much less invited to participate creatively, but Danny and the producers wanted me there, and it was an amazing experience getting to contribute to the production process. The availability of Fabio for an afternoon led to a quick rewrite to create a scene for him and the dudes. The need to raise the stakes in the third act meant writing a role for Andy Dick and a sequence involving a creepy French guy and aggressive ostriches. It was an intense time jam-packed with creative collaboration, problem solving and lots of laughs. I was lucky that the producers felt that my voice was important to preserve, which led to crew members and department heads asking me questions throughout the process. “Hey Phil, what do you think the ‘dude’ / ‘sweet’ tattoos should look like? Hey Phil, what kind of car do you think the dudes should drive? Hey Phil, how stoned were you when you wrote the ‘and then’ scene?”

With the success of the movie came more opportunities for me. I sold several feature pitches, including a Quake-style gaming pitch called Modern Day Warrior with Jack Black that had me thrilled to be driving half of Tenacious D around to pitch meetings. There was a Producers-style project with rap music instead of a musical that I spent a month in a cheap hotel on the beach in Belize writing. There was a project called Ugly as Sh*t that Jamie Foxx was attached to, where I got to watch in awe as Jamie would walk into pitch meetings as cool as James Bond, crack everyone up as he transformed into Jerry Lewis, then leave with the confidence of Miles Davis. And during this time I was still writing and producing on That ‘70s Show, which ran for eight seasons and continues to air today in syndication (you Gen Zers might have to ask a Gen Xer what reruns are).

But comedy has changed dramatically in the past quarter century. This became apparent to me upon a recent DWMC rewatch, when I was struck by just how much I cringed at the humor. And it wasn’t just because I was watching it with my kids, for whom I am the ultimate source of cringe. What made me cringe is how, 25 years later, some of the comedy feels so dated, even offensive. Sure, the tone is light and silly and the humor comes largely from the charming and stone-y performances of Ashton and Seann. But there is plenty of humor that plays at the expense of transgender people, ethnic minorities, women, gay men, religious cults and Fabio. Did it feel this cringey 25 years ago? I don’t think so. The humor seemed appropriate at the time. But then again, so did Matchbox Twenty.

Box office returns have been disappointing of late for all genres, even the seemingly unstoppable tide of big budget Marvel movies and Pixar sequels. Comedies used to be the preferred genre of movies that could be made on the cheap without stars but with profitable results; now that role has gone to horror movies. The whole concept of theatrical distribution that makes up so much of the foundation of the business is now in question, as the aftershocks of COVID and the rise of the streamers continue to challenge our assumptions about how audiences consume content. And while there have been big-picture industry changes over the last 25 years, there are also the personal changes in our own lives. Just consider mine.

Twenty five years ago I was a young screenwriter writing broad, crude humor to sell into a marketplace that valued it. Over time, that changed. After DWMC, nothing I wrote got made, and eventually the pitches stopped selling, and the specs I wrote didn’t gain any traction. After That ‘70s Show ended its run, I wrote and pitched many pilots that either didn’t sell or didn’t get made. It got to the point where I wondered if I should continue pursuing a career that had started out so promising. And the bigger question was whether or not I was happy doing it. The answer to that question was a resounding no. I had become bitter and resentful. After so much early success I was experiencing defeat, and even though I didn’t enjoy it and wanted to make a change, I was frustrated because I didn’t know what that change could be.

Eventually I figured out what I wanted that change to look like. I went back to graduate school, got my master’s degree in psychology and became a therapist. That’s right, the guy who wrote a movie about two stoners who can’t find their car now wants to ask you about your mother. And today I’m still writing, but instead of movies like Dude, Where’s My Car?, I write self help books like Dude, Where’s My Car-tharsis? Much of my work as a therapist is with clients going through transitions involving their careers and relationships, and processing how we deal with these changes. How when we hold on too tightly to the idea of how things used to be, we prevent ourselves from being able to accept how things are now, and how they could be in the future. Which I think describes our personal journeys in life, as well as the evolution of the entertainment industry.

Twenty five years is a long time, but it feels like it went by in the blink of an eye. Who knows what our world will look like 25 years from now, in the year 2050. Will the production of feature films still be profitable? Will movie theaters still exist? Will South Park still be on the air? Will people even know what I mean when I say “on the air”? I don’t know the answers to these questions, but I’m planning on being around to find out. And then…

Phil Stark is a screenwriter, author and licensed marriage and family therapist in Los Angeles.