Talk to Mira Nair about the role she played in the political formation of Zohran Mamdani — the 34-year-old prodigal mayor-elect of New York City and, as it happens, her only child — and many facts will soon tumble out.

There was the relentless canvassing she did for him in far-flung homes across Queens and the Bronx.

There was the multicultural perspective the filmmaker and her academic husband, Mahmood Mamdani, imbued in their son that would eventually emerge in his speeches and policies.

There was even Nair’s decision to bring a pre-politics Zohran to her sets, where he supervised music and stood in for actors, picking up the showbiz skills that would serve him so well on the trail.

But of all the ways in which the director contributed to her son’s supersonic political rise, none fills her with as much pride as this: running an impromptu campaign headquarters in her home.

“At 6 o’clock in the morning, I’d get a call from Staten Island. ‘Mamma, we’re coming over.’ And they would come in like the Beat Generation, like deadbeats, with a little car they’d park out there, all of them 30 or 35 years old, and set up their laptops and take over every room,” Nair says, describing the past year of her life. She gestures around the sprawling apartment overlooking the Hudson just a block from Columbia University, in the home where Mamdani grew up and in whose study Nair currently sits. “They would keep working until 4. Zohran would sleep a little, wake up at 5, fresh shirt, back in the car. It was like a movie,” she says, then edits the scene: “The early part of the movie, where you’re not sure if it’s going to work.”

The comparison suits the candidate’s cinematic arc. But it also applies more literally. Perhaps not since Reagan — or, OK, Trump — has show business so prominently shaped an elected official. During a 45-year career, Nair has mined pieces of her worldview for her films and extracted cues from her films for her son — which is why if you gaze upon the street poverty of Salaam Bombay!, the multiracial romance of Mississippi Masala, the joyful South Asian dysfunction of Monsoon Wedding, the assimilation/de-assimilation journey of The Namesake and the pointed challenging of Americans’ anti-Muslim bias in The Reluctant Fundamentalist, you’ll find not only her messages to the young politician but a treasure map of his own psyche.

“What I love so much about Zohran is that he embraces the multiplicity of our lives in the most natural way — this mosaic that is our city but that no one has seen until this young man came along,” Nair says. “It’s the theme of ‘who is considered marginal.’ That is the question I have asked all my life and in all my films. And now he’s asking it on the biggest stage.”

Also, there’s the rapping.

***

Finding connections between filmmaking and politics can seem like a game from the outside, a journalist’s tortured projection. Campaigning contains more elements of showbiz than it used to, sure, but it also involves plenty of social media, and no one says that a successful politician also could be a tech executive.

Yet ever since Mamdani successfully ran for the New York State Assembly in 2020, Nair says she can’t stop seeing how his upbringing in the house of a filmmaker shaped his political skills.

“To get a feature greenlit takes mountains of work; it’s very similar to campaigning,” she says. “Another great thing is, when you make movies, you have to reach many more people than just your family, and I always have made films that tried to do that. The struggle was how not to pander and explain yourself but to still find stories and ways of telling [them] that people see themselves in. Which is exactly what his campaign was.”

Even Mamdani’s decision to lean in to the provocative Democratic Socialist label can be traced back to a directorial philosophy from Nair, who has largely eschewed Hollywood and asked audiences and the industry to meet her where she is. “It’s not disrespectfully thumbing your nose [at mainstream expectation], but it’s also being very clear on where you stand,” she says. “It’s, ‘I’ll use several languages in the same scene and not subtitle it’ ” — as she does in several films — “which is a lot like [Mamdani’s], ‘I’ll teach you how to say my name, but then you have to say it right.’ “

Nair looks at the brightly lit room around her. Heavily curated with art and books (or, in the case of Nair’s study, books about art), the apartment contains few current references to its new status as childhood home of a mayor; campaign postcards in an ornate fixture outside the front door are among the few reminders. But her son’s spirit lingers, if only because Nair, despite half-heartedly repeating she doesn’t want to talk about him, takes little prodding to do so. She refers to a sign, “Kindness,” that hangs (prominently) in the bathroom. “We always tried to teach Zohran that. And he brings that lesson with him everywhere.”

At 68, Nair has lost a little bit of the regal posture of her younger years but none of the radiance. Her words can be direct, but you don’t always take note; her warm laugh can cut the sharpness of the opinion she just gave you. “Fierce in a good way — mostly,” says an indie film veteran who has known her for decades, noting how, in a business marked by soft flatteries and frequent compromises, Nair has shown herself allergic to both. Those who watched Mamdani’s election night “turn the volume up” code-switch and asked where it came from would not be surprised after interacting with his mother.

But also evident in Nair is the same Clintonian gift as her son — the feeling that the speaker is sharing a bond only with you. Despite having met her just a few minutes earlier, the director helps a young photo-shoot makeup artist feel better about an impending difficult Thanksgiving conversation with her mother. Such a skill certainly comes in handy on set, with its numerous entertainment egos, and will be needed in Gracie Mansion, with its numerous political egos. “All these skills, Zohran has absorbed them his whole life,” Nair says. (She always pronounces it Zoh-RAN, except for the few times she goes with a hard twang — ZOH-rayhn — to imitate an unread American.) “I love that he finds a way to get across his ideas. That is his great gift — his connection.”

Nair made her own attempts to connect with voters, which can seem a little like something out of a folk tale (or The Namesake). Every week from January to June this year, she’d pair up with a volunteer from the campaign and trek door-to-door in a new neighborhood on behalf of Zohran Mamdani, one of the country’s most acclaimed international filmmakers out there knocking like a common Bed-Stuy hipster. She would refrain from identifying the candidate as her son unless the person said they were already voting for him; she says she wanted to use persuasion, not shame, though of course the move also had the effect of protecting her from getting yelled at.

So entwined is Mamdani with his mom’s film company that when the mayor-elect returned a text from rival Curtis Sliwa with a phone call on election night — the Republican was looking to concede — the number came up as Nair’s Mirabai Films, according to Sliwa, prompting him at first to decline the call.

Incidentally, Nair has respect for the Guardian Angel — “I really like Curtis,” she says, a verb she would not use for campaign rival Andrew Cuomo and his big-monied donors: “$25 million in the last four weeks after the $19 million before that; you could feel the percolation of that in the extent of the hate and vulgarity in some people’s minds.”

At a few points in the past several months, Nair says, the threats against the Mamdani family grew loud enough that she became fearful for her security. “I called Zohran, and I said, ‘What should I do?’ And he said, ‘Just go and canvass.’ ” She laughs at her son’s job-first reaction but says it helped. (Mamdani’s relentless work ethic might be explained partly, if one might indulge a reporter’s subjective experience, by the only child’s desire to keep pressing because the specter of parental disappointment hovers regularly just out of frame.)

The director also finessed Hollywood. “In October, we were doing a film industry event for the uncommitted,” she says. “It was hard to find that person, but we found them in Hollywood for sure.” Asked if most industry liberals weren’t already on board, she says, “But some were not. The lawyers and all.”

As much as Mamdani has a mandate with just over 50 percent of the tally and 1 million votes, some of the people who didn’t vote for him really didn’t vote for him, and more diligent capitalists, conservatives, law enforcement officials and pro-Israel Jews have all, for their own reasons, expressed wariness about him.

The pro-Israel constituency in particular has been contentious. Some 1.3 million Jews live in New York City, more than the entirety of his voting base, and a good number of them are supporters of a two-state solution and skeptical of Mamdani’s view that the country should not principally be a Jewish state. (His handling of a raucous protest outside a Manhattan synagogue over an Israel real estate seminar it hosted in late November did little to calm the waters — his spokeswoman said, “These sacred spaces should not be used to promote activities in violation of international law,” referring to the seminar’s information about relocation to the West Bank, among many other places in Israel, though Mamdani soon partly walked back that reaction.)

Nair declines to speak on the record about Mamdani’s attitude to Jews or Israel. For anyone with a Jewish mother, it can be hard to square how Nair evokes the type while also holding views so at odds with many Jewish mothers (and children). Nair and Mamdani believe that Israel’s primarily Jewish character should be done away with — Nair once refused an invitation to a festival in Haifa by saying she “will go to Israel when the state does not privilege one religion over another.” And it must live, uneasily, with an overall vibe that would make any Jewish mother smile — the contradiction not evaporating no matter how many times one turns it over, just sitting there in its irresolvability, like a social-cultural tension right out of a Mira Nair film.

***

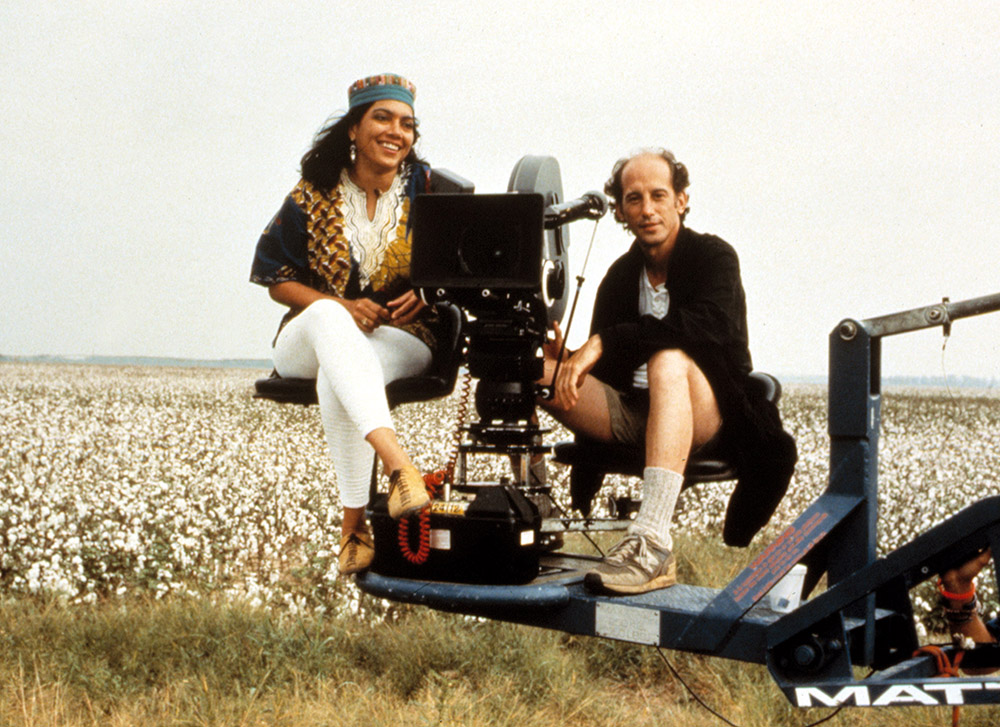

Nair’s career has not been as meteoric as her son’s. After making several little-watched documentaries in India in the 1980s, she finally got her break in 1988 when Salaam Bombay!, a scripted movie about the city’s poor street kids drawn from her own documentary research, landed the Camera d’Or at Cannes and a foreign-language Oscar nomination. Nair’s narrative follow-up, 1991’s Mississippi Masala, drew further acclaim when it yielded a frank conversation about prejudices in both the Indian and Black communities. (It also yielded her second husband, Mahmood Mamdani, a Ugandan expert whom she interviewed for research, shortly after she divorced her first husband, photographer Mitch Epstein and her former professor turned producing partner.)

But it was only with her gleeful family romp Monsoon Wedding a decade later that Nair became an indie darling. The story of a mayhem-filled arranged marriage in Delhi universalized the particular. Everyone could see in the subcontinental specificity the chaos of their own families, and the film’s breakout at the box office heralded Nair as a directing trailblazer for the new century. Raised in India in the Hindu faith, Nair came to the U.S. to attend Harvard as an undergraduate in the ’70s and has spent much of her adult life here while always casting an eye back to her and Mahmood Mamdani’s birthplaces. Now the culture was catching up to her globalism.

Nair’s career post-Monsoon has been up and down — a respectful adaptation of Vanity Fair with Reese Witherspoon; a well-crafted, stripped-down adaptation of Jhumpa Lahiri’s acclaimed immigrant epic The Namesake; a flopped Amelia Earhart picture with Searchlight. (Many of her projects feature a free-spirited, morally assured female protagonist; one hardly needs an advanced psychology degree to see them as stand-ins for Nair herself.)

And then came 2013’s The Reluctant Fundamentalist, about a successful Pakistani-Muslim immigrant to the U.S. confronting racism after Sept. 11, and the 2016 Ugandan chess tale Queen of Katwe, about a young girl using the game to flout sexism in her community.

It was on these last two films that Zohran became a major factor. As much as Nair influenced her son’s career, he also has impacted hers. As a 21-year-old Bowdoin student in the midst of founding the school’s Students for Justice in Palestine chapter, Mamdani, a Muslim, strongly encouraged her to make Fundamentalist, eager to show how even Islamist radicals were not born but made — largely, in his view, by mistreatment at the hands of the West, as Riz Ahmed’s lead character suggests.

Mamdani had been involved in Nair’s film efforts before — Kal Penn is in The Namesake because a teenage Zohran liked him in Harold & Kumar and tipped off his mother. And anyone left wondering what a Nair-flavored Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire would have looked like might point to Mamdani, who as a 14-year-old, with his mother in advanced discussions to direct the movie, told her that “anyone can direct Harry Potter; only you can direct The Namesake,” prompting her to withdraw. But now he was really a voice in the room. Three years after urging her to direct Fundamentalist, Mamdani, now a newly minted millennial rapper named Young Cardamom, became a guiding force on Queen of Katwe. He helped to find many of the kid background players in Kampala, where the family spends a lot of time; curated songs as music supervisor; and even rapped the lead track.

Earning solid reviews after a push from Disney, Katwe now is perhaps best known for its viral hit “#1 Spice” (“It’s the Number 1 spice/eat in the morning and roll like a dice”), a duet that Mamdani co-wrote and co-performed in his Young Cardamom guise.

To watch the video now is to inhabit a YouTube thought experiment. Without knowledge of who Mamdani became, the music video plays like B-roll for a cringe VH1 retrospective (Did he just step out of the television with a gray patterned suit that matched the wallpaper?). But with the hindsight of the 2025 campaign, it is filled with signifiers, the emergence from the TV to dazzle the local villagers a portent of a savvy politician who got elected by stepping away from the screen to meet physically with voters. “It actually is quite prophetic,” says Nair, who directed the video of her son and pushed ambivalent Disney executives to finance and promote it. So enamored was Nair of Mamdani’s performance skills, she even wanted to cast him in her next project, a Netflix limited-series adaptation of Vikram Seth’s post-Partition novel A Suitable Boy, in the title role. But Mamdani demurred, saying he didn’t see himself as an actor.

***

After a decade toiling in other venues — a stage musical of Monsoon Wedding, Suitable Boy, a strike-scuttled Johnny Depp-starring film of the epic novel Shantaram — Nair is finally returning to her feature roots. A few days after Thanksgiving, she is set to travel to Budapest to scout her new film — a biopic about the proto avant-garde, early 20th century Hungarian-Indian artist Amrita Sher-Gil, who upended the art world and died tragically at 28 — that Nair will shoot in early 2026 in Europe and India. Financed equally by Miramax and art-world donors, the film will take Nair back to the India-set films of her early career and, with Sher-Gil, double down on her principled-female contrarianism. Here Zohran lives again, too, in the character of a charming iconoclast who achieved rapid success at a young age.

The film also is Nair’s latest stiff-arming of mainstream Hollywood. Nair expresses little patience for the peers who try a one-for-them approach. “They all say, ‘No, no, no, I’ll return to make my important movie after I make James Bond,’ ” she says, joking but not joking in her mellifluously accented English. “They’re all friends of mine, and I adore them, but a lot of people just want to make money,” she adds. “If they can buy your integrity, you don’t have it.”

Cinecom Pictures/Courtesy Everett Collection; Samuel Goldwyn Films/Courtesy Everett Collection; USA Films/Courtesy Everett Collection

***

A few days after our interview, Nair is walking through Bryant Park. She moves unnoticed through the midtown swirl, the holiday craft stands and streams of tourists unaware that the mother of the city’s soon-to-be mayor is striding among them en route to the subway. “I put my production out into the world,” she says. “He got the box office; he more than won the weekend. Really he’s beyond all analogies of film. Because what he is is hope for a lot of people in the world.” She says she is not worried Zohran will struggle in a job that has chewed up far more seasoned politicians. “It’s a big thing for him to carry that hope, but he’ll carry it beautifully,” she says. Nair adds that she would have been happy with any professional path for her son, save for the now-aborted rap career. (“I felt relief about that,” she notes with a laugh.)

Asked whether she is surprised that Mamdani seemed to work his jujitsu on Donald Trump a few days earlier, she gives another chuckle and says, “No, not at all,” as if to suggest she’s watched him pull off greater magic tricks. Then she pauses and contemplates why the president seemed to flip to Zohran’s side. “Respecting elders — knowing how to talk to them — that’s what we’ve been doing his whole life,” she says. “He just paid attention.”

This story appeared in the Dec. 3 issue of The Hollywood Reporter magazine. Click here to subscribe.