The sweetest, spiciest and most shocking Sundance stories are ones you don’t hear at Q&As inside the Eccles or Egyptian.

Like the time Thirteen writer-director Catherine Hardwicke was forced to spend much of her festival debut playing bodyguard to keep male filmmakers from hitting on the 14-year-old star of her film, Nikki Reed. Or the moment Todd Field shooed respected Fox Searchlight president Peter Rice away from buying his future best picture Oscar nominee In the Bedroom, only to find himself “screaming, crying and almost throwing up” in a bathroom when a ruthless Harvey Weinstein got it for Miramax (Field, in return, was asked to skip future fest negotiations). Or the time Nicole Holofcener’s airplane hit a bird, leaving her stranded until a resourceful pair of producers booked a private jet during a scary snowstorm (fortunately for her, she packed Valium). Or when Janicza Bravo rushed seriously ill Zola star Riley Keough to the ER or when Clint Bentley accidentally took weed gummies before Sony Pictures Classics called to make a deal for his debut feature, Jockey?

That’s just a sampling of the juicy only-at-Sundance tales The Hollywood Reporter fielded during an exclusive oral history to mark the fest’s final bow in Park City before the circus leaves town for a new home in Boulder, Colorado. Who better to rewind the times than a prestigious group of filmmakers who had their lives changed by what went down during America’s most consequential gathering of independent film insiders?

HELLO, SUNDANCE

JOHN SAYLES (1980’s Return of the Secaucus Seven) In 1981, the first year in Park City, I went when Return of the Secaucus Seven won second place. It was a nice indie and international festival but had none of the heat that Sundance and Robert Redford’s backing brought to it. Suddenly there were a few mainstream-movie businesspeople at the screenings, and all the independent distributors sent somebody — eventually studio execs got to ski on company expense accounts.

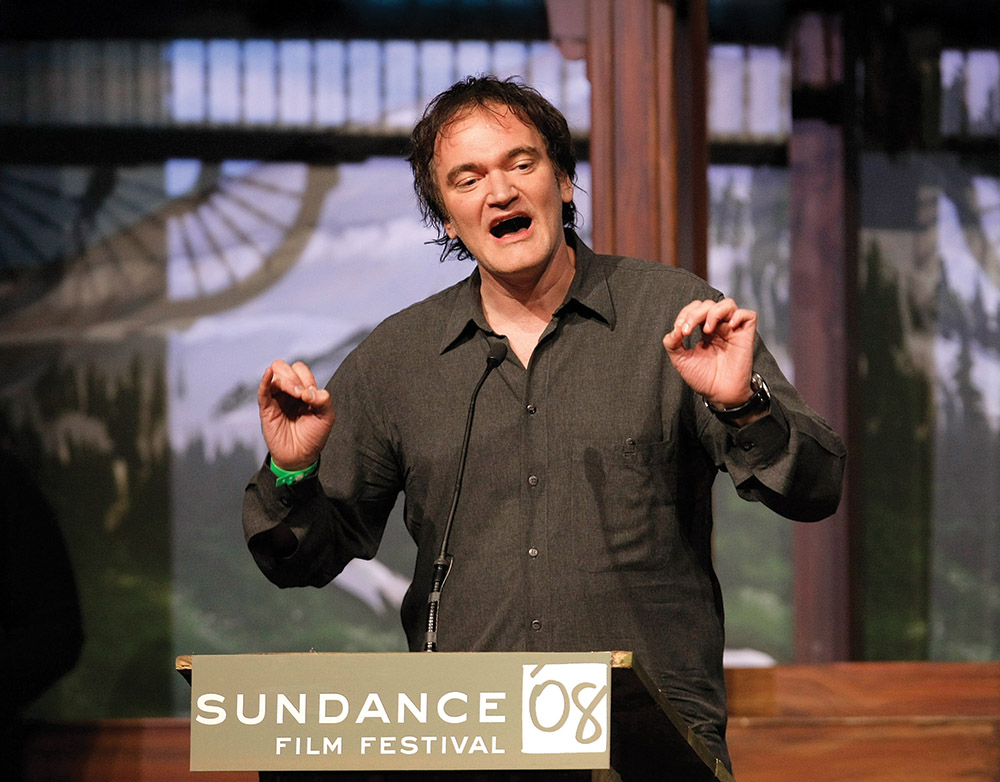

QUENTIN TARANTINO (1992’s Reservoir Dogs) None of us independent filmmakers would be where we are without the Sundance Institute and Film Festival. It was a launchpad. I remember being accepted to the lab and showing up to literally do scenes from my script with Terry Gilliam, Volker Schlöndorff and Stanley Donen. They were in my editing room as I edited my first scene on videocassette. We made a cut and they would write notes like Olympic judges.

Jemal Countess/WireImage

RICHARD LINKLATER (1991’s Slacker) As someone in the indie film world in the 1980s, I’d heard about Sundance for years as a rustic festival people were striving to get into. At the same time, Dallas had the USA Film Festival, so I can’t blame Sundance for changing the name.

JAMES MANGOLD (1995’s Heavy) I went there first trying to raise money for Heavy and to meet people with my producer, Richard Miller. It was a wide-eyed experience. That was ‘93 or ‘94, sleeping on couches in condos. It was still the more wild and wooly, less fully [formed] Sundance as fame landed. I remember seeing everyone from Allison Anders to Bryan Singer to John Sayles. It was a heady world of young filmmakers with first movies, shorts or projects. Wes [Anderson] was there with his short, Bottle Rocket. I was just so green. It felt like being caught in a whirlwind.

DARREN ARONOFSKY (1998’s Pi) I first went before I had a film, to support friends that got in, people like Scott Silver, who made Johns, and Mark Waters with House of Yes. It was during that time that I saw films like Todd Solondz’s Welcome to the Dollhouse and [Leon Gast’s Muhammad Ali] documentary When We Were Kings. It gave me courage and the idea that if you made a movie and it was good, you would find an audience. Todd’s film was so unique in vision, spirit and casting and was so successful artistically that it got me super psyched. It really helped me believe in the thing that was right in front of me, which was Pi.

ALEXANDER PAYNE My thesis film from UCLA [The Passion of Martin] got accepted to play with another short in 1991. I was there when it was really still small and — this is a much overused term — genuinely intimate. You got to know everybody. I was there with Richard Linklater when he had Slacker, Jennie Livingston for Paris Is Burning and Todd Haynes for Poison. I hung out for most of the festival and had a great time.

JUSTIN LIN (2002’s Better Luck Tomorrow) I’m old, so in the ‘90s, when I was in film school at UCLA, there was no internet. Every month I went to the newsstand in Westwood to buy Filmmaker magazine. It was my only connection to the industry. I read about a mythology coming out of Sundance with John Sayles, [Robert Rodriguez’s] El Mariachi and John Sloss, all these mythical figures. I was lucky to get into UCLA but even then you questioned how real a Hollywood career could be, but Sundance was one of the very clear paths. If you could get there and prove yourself, it could create opportunity. Sundance presented like a meritocracy — it was hope and opportunity.

CATHERINE HARDWICKE (2003’s Thirteen) I grew up in Texas on Westerns and blockbusters, so when I went to Sundance, still the U.S. Film Festival, my head exploded at how personal and intimate films could be. I saw Steven Soderbergh’s sex, lies, and videotape, and at the screening he got up and spoke eloquently about it. I was so moved that when he came out of the theater, I said, “Your film is so exciting, I’ll do anything. If you need me to lie down on the sidewalk on the snow so you can walk across my back, I’ll do it.” The guy looked at me like, are you fucking nuts? I’ve never seen him since.

George Pimentel/WireImage

KENNETH LONERGAN (2000’s You Can Count on Me) When you make a movie that’s looking for a distributor, you do the festival circuit. Sundance was always the first goal. We were lucky to get in with [You Can Count on Me]. Every year people would say, “Oh my god, it’s gotten so commercial now,” and I’m sure they’ve been saying that since the second year they ever did it. It’s now very much a market and a place where there are a million films. But they love movies.

SIAN HEDER (2016’s Tallulah, 2021’s CODA) In high school at Cambridge Rindge and Latin, I heard about edgy indie Sundance movies like Reservoir Dogs and Reality Bites. As I became interested in directing, there were so many women who came out of Sundance whose careers I could look to — Catherine Hardwicke, Gina Prince-Bythewood, Karyn Kusama, Allison Anders with Gas Food Lodging.

ZACH BRAFF (2004’s Garden State) When I was in film school at Northwestern, Sundance came on my radar as a dream scenario. Your indie would get into the festival, have a good reaction and distributors would fight over you. I read books and articles and learned of the magic that happened for Steve Soderbergh with sex, lies, and videotape and Quentin Tarantino with Reservoir Dogs. It’s so hard to get in, but if you managed to have a hit, it was like winning the lottery.

CRAIG BREWER (2005’s Hustle & Flow) All my Memphis friends rented a place in Park City during Sundance, but they wouldn’t go to the festival. They just wanted to be in Park City and wound up going to the No Dance Film Festival, a lower-tier event at the same time. They asked me to throw in a couple hundred dollars and sleep on a couch. I was worried about sounding too arrogant, but I didn’t want to go until I was invited.

RYAN COOGLER (2013’s Fruitvale Station) In my last meeting with Michelle Satter [founding senior director of the Sundance Institute’s artist programs], she laid out a blueprint to make sure I was taken care of in the process of getting my movie made. Before we applied, she gave me a bunch of notes for Fruitvale Station. She watched a work-in-progress cut and came down pretty hard on me with incredible feedback that we were able to incorporate. She’s like a producer, a teacher, a maternal figure, advocate, visionary, all rolled up into one. An incredible leader. Then we applied to the festival and got in.

Fred Hayes/Getty Images

KIMBERLY PEIRCE (Boys Don’t Cry, a product of the labs): As I was running out of time and had hit another wall, I called Michelle Satter. She sent Craig McCay, the editor of Silence of the Lambs and others, to my edit room to look at it and see its value and convince my producers and other people I just needed more time. It was my dream to open Boys Don’t Cry at Sundance because the labs had helped me bring it to life, but we were nowhere near done and out of money. They said there was one long shot they did not think would work because it never had: “If you edit all day long with your editor Lee Percy and go and find an editor who will work the night shift, for free, and starting now, you work a double shift and make a reel. We’ll take it to the Sundance Film Festival and see, but we don’t think it’s going to happen so get ready to leave the editing room.” I found an editor, she kindly worked for free, and I went back to the edit room and worked the double shift — Boys the movie all day, Boys the reel all night. Sort of like my grad school days on the double shift. We made a reel. It was too long — 20 minutes — but wild and jam-packed with great images, frenetic real life scenes and rock music like Boston’s “More Than a Feeling,” The Minutemen, all kinds of indie rock, Lynyrd Skynyrd, southern rock.

JAMES WAN (2004’s Saw) The touchstone horror film that came out of Sundance was The Blair Witch Project. So even though, at that particular point, Sundance wasn’t necessarily known as a destination for horror projects per se, the success of Blair Witch opened our eyes up to the possibility of that festival being a breakout ground for filmmakers like us who wanted to make scary movies. We idolized Blair Witch and were hoping that we would get into Sundance’s Midnight programming just like that movie did.

JAY DUPLASS (2003’s This Is John, 2005’s The Puffy Chair) In 2003, it was the only festival that could actually make a difference in your career. Every other festival at that time, including South by Southwest, was like a regional festival.

MARIELLE HELLER (2015’s The Diary of a Teenage Girl) When I got pregnant, in my very first doctor’s appointment, one of my first questions was, “If my movie gets into Sundance, will I be able to go?”

YOU’RE EITHER IN OR YOU’RE OUT

LINKLATER The first time I applied was 1990 with an early cut of Slacker, and I didn’t get in. Slacker is a weird film, so I took it to Berlin and showed it in the market. We ended up premiering at the USA Film Festival in Dallas in 1990 but finally had a breakthrough in June of that year in Seattle. Tom Bernard and Michael Barker, who then worked at Orion Classics before founding Sony Pictures Classics, picked it up for distribution. It was their idea to premiere at Sundance in 1991. We got in the narrative competition, too, not midnight or some fringe section. Back then, the competition didn’t have a lot of name actors in any of the movies. It wasn’t a forum for stars yet.

ARONOFSKY I was pretty stressed [about getting in] and so I left my Manhattan apartment to go to my parents’ house in Brooklyn to hide from the world. When my phone rang, a person on the other line asked about the running time on my movie. I was confused. “No one’s called you?” they asked. “Well, you got in.” I called the team from Pi, and we met at a bar on the Lower East Side where everyone kept randomly breaking out in applause because we were so excited.

ED BURNS (1995’s The Brothers McMullen) I spent a year sending McMullen to every distributor, to every agent and manager, and trying to get into every festival. I had a stack of rejection letters a mile high that I saved to fuel my passion, but it really felt like the end of the road. At the time, I worked as a production assistant at Entertainment Tonight when Robert Redford was doing a junket for Quiz Show [the 1994 movie Redford directed]. We were in a hotel, and when he and his publicist exited one door of the suite, I slipped out the other to meet him at the elevator. I gave him my spiel and handed him a rough cut on VHS. He said, “Alright, we’ll take a look.” Two or three months later, I got the call that we were in.

TODD FIELD (2001’s In the Bedroom) Getting a film into Sundance was always the dream. My first experience came when I submitted a short film I made while at AFI. At the time, AFI had a stupid rule that your student film couldn’t be accepted or screened at the festival, so they had to call AFI’s Jean Firstenberg to sort it out. It became a whole fight. My thesis film [Nonnie & Alex] that I made with [wife Serena Rathburn] got in and wound up receiving [honorable mention from the jury] in 1995. The first year I went to Sundance, Alex Vlacos and I slept on the floor of what felt like a lumberyard. That’s the way you did it back then. This was before the corporatization of the festival.

KARYN KUSAMA (2000’s Girlfight) We sent in a quite rough cut of [Girlfight], maybe three or four weeks into editing. When I was mixing at Sound One in the old Brill Building in New York, I got a call in late October from [senior programmer] Shari Frilot who said, “We’d like to invite you to competition.” I was so focused on the mix because every moment was so precious with our tiny budget that I couldn’t process what it meant. I said “thank you” and figured they would follow up.

HARDWICKE With the nature of Thirteen being so indie and raw, and the fact that it was co-written with a 13-year-old girl, we had a dream of going to Sundance. Our wonderful editor, Nancy Richardson, suggested a tiny edit to a frame by saying, “That’ll get us into Sundance.” We were hoping and praying with our fingers crossed. We finished it literally the night before deadline. We were an odd little duck because they didn’t know how to do the coating on it since it was Super 16-millimeter.

LIN Before we got into Sundance, we had an industry screening at FotoKem in Burbank. I invited the cast because I wasn’t sure if we would get into festivals, so I wanted them to get some work out of it. I told them to invite whoever, and all these agents, managers and casting directors showed up. So many people called me stupid that night for making a movie with an all-Asian American cast. It was horrible. Two weeks later, we got into Sundance, and a bunch of those same people tried to sign me, saying, “What a great movie.” I was like, “Wait a minute, you told me I was stupid two weeks ago!”

LAUREN GREENFIELD (2012’s The Queen of Versailles) We submitted The Queen of Versailles, and [festival director] John Cooper called to tell me that not only did we make it in, but we were chosen for opening night at the Eccles. Cooper wrote the blurb about the film and called it “a riches-to-rags story.” Based on that, our subjects, Jackie and David Siegel, sued me, my husband and producing partner Frank Evers, and Sundance. Sundance stood firm, and we showed the film opening night. There’s a line in the movie when David Siegel says, “This is my riches-to-rags story.” It was so quiet you could’ve heard a pin drop, and there were audible gasps because the lawsuit had been all over the news.

CLINT BENTLEY (2021’s Jockey, 2025’s Train Dreams) I submitted every short I ever made and never got in, but it almost felt like a natural step. “All right, we got to get our Sundance rejection.” You start to realize that if you haven’t gotten the call by a certain date in November, you weren’t getting in. A lot of filmmakers had their Thanksgiving holidays ruined.

AVA DUVERNAY (2012’s Middle of Nowhere) I submitted seven times. I’d applied to all of the labs for four years. Never got in. I submitted a short, my first documentary, my first feature, I Will Follow. The Middle of Nowhere was my second narrative feature, and it got into the dramatic competition. I was still working as a full-time publicist for the studios at my own agency, so my first thought was, “Now I have to tell people.” No one knew I was making movies.

KEVIN SMITH (1994’s Clerks) I went from being a guy working at a convenience store to a guy who made films about working at a convenience store. If you tell somebody now that you got into Sundance, everybody knows what that is. But in November 1993, when I said, “Oh my God, I got into Sundance!” people were like, “What is that?”

CHLOÉ ZHAO (2015’s Songs My Brothers Taught Me) I went to the lab with [Songs My Brothers Taught Me], so once I made the film, I actually also did the first Sundance sound lab that they collaborated on with Skywalker Ranch. It went from the Sundance writing lab to the director’s lab and then, in post, the sound lab. Sundance supported the film in every possible way, so I really was relieved that I got in!

MEGAN PARK (2024’s My Old Ass) My first film, The Fallout, went to SXSW and won every award it was eligible for, but that was during the pandemic. I got a phone call from the festival director, Janet [Pierson], who told me the good news. I was in my backyard and said, “Wow, that’s so cool, thank you.” She said “bye” and hung up. That was my entire SXSW experience. The reality of getting into Sundance was a dream come true. Tom Ackerley from Lucky Chap kept saying, “Soak this in, Megan. You are experiencing a peak Sundance experience.” I was three months pregnant, violently ill and trying to hide it the entire time.

JAY DUPLASS (2003’s This is John) It was still mostly landlines at that point, and our contact info was my parents’ home phone even though I was 30 years old. That gives you an idea where we were in our lives. I got a call and a voice said, “This is Trevor Groth, we would like to program This Is John at the Sundance Film Festival.” I thought it was [filmmaker] David Zellner pranking me. He edited the film and a few weeks prior, we were joking that we should lie about the budget because we didn’t think Sundance would program a $3 short.

BENTLEY My wife and I were doing a renovation on our house. I was waiting on calls from vendors to buy tile. A random number called and I picked up. It was [programmer] John Nein. My mind went blank. It was during the pandemic, so we were working from home. I went into the living room to tell my wife and started crying. She thought it was something bad. She said, “It’s going to be OK, whatever it is.” I was like, “It’s amazing!”

MANGOLD We got accepted in the festival, which saved the movie. I mean, I only got the financing to finish the movie because they had accepted it. I really didn’t have the money to get it there.

PAYNE I come from nothing and went to film school to start making films. There’s a rush you get as a film student when your film gets accepted to a festival. It’s so hard to make movies and it’s so hard to do a decent one, so it’s a validation for a young filmmaker to be accepted. Even if it’s a Podunk film festival, filmmakers still fucking pay to travel to some Podunk film festival to have their film seen by 30 people. It’s a big deal. Multiply that by what happens at Sundance with all the publicity, promotion and enthusiasm. There was nothing like Sundance at the time.

ARONOFSKY Before Sundance, IFC, which had just started, was circling Pi and wanted it as one of their first acquisitions. But we got into an argument about a scene where Stanley Herman, an actor I had been working with since high school, sings an Irving Berlin song on the subway. We didn’t have the rights, and it would be two years before it entered the public domain. I tried to change the song but couldn’t figure it out, and it would’ve cost us $25,000, but IFC refused to pay for it. We said, “Screw you guys, we’re going to keep the film.” We didn’t make a deal, which might’ve been the luckiest not-making-a-deal situation because it allowed me to go to Sundance as a free spirit. It changed the destiny of the film.

NEWBIES IN PARK CITY

SAYLES We premiered City of Hope in 1991 and rented a chalet kind of joint and told anybody who worked on the film they could stay with us if they could get there. That had become a kind of tradition because so many first films were made by people paid little or nothing so hosting a reunion in Park City, if you got in the competition, was a nice payback.

LINKLATER My first Sundance, we had a dorm-like situation. I had a roommate, filmmaker Joseph Vasquez, who had a movie in the festival, Hangin’ With the Homeboys. He was a New York bro-y kind of filmmaker, very real. I liked him a lot. He had one room and I had the other, where I stayed with my girlfriend and four friends. It was a campout vibe. Joe passed away a few years later, sadly.

BURNS We rented a tiny room on Main Street with all these bunk beds for the cast and I to share. There were eight of us in there.

SMITH We had at least eight people in a one-bedroom condo.

HELLER I went to Sundance because my friend Ryan Coogler had Fruitvale Station premiering. I went by myself and my friend offered a shared house with an extra bunk bed for $100. It was Lynn Shelton’s room. I had never met Lynn, and I stayed in the living room, just a stranger and so in the way.

LONERGAN I’d never been to a big film festival before. I’d never been to Sundance or Utah, and the film hadn’t been seen much. You fly into Salt Lake and it’s a long and winding drive through the mountains to Park City and we did it in the dark so you couldn’t see much. The producers rented a condo for us and it was me, Matthew Broderick and Jon Tenney together. Laura Linney and Mark Ruffalo were with us in the beginning but left early. It was a nice condo and we got driven around in the snow. We felt very fancy.

BRAFF I first went as an actor. My first movie was [Woody Allen’s] Manhattan Murder Mystery, but my first big part was Getting to Know You, which got in. A year later, I went back to Sundance for Greg Berlanti’s The Broken Hearts Club. I was blown away and so wide-eyed. It was so magical to walk down Main Street past the most famous beloved actors in the world, see movies and go to parties. I had never experienced anything like it in my whole life. When I went back with Garden State, Gary Gilbert rented a big house in Deer Valley. Not only did my film get in but we stayed in this ski-in, ski-out, big-ass mansion. I’d never seen a house like that before, it was a dream weekend. Pam Abdy stayed there, Rich Klubeck, Peter Sarsgaard, Danny DeVito, Jean Smart.

RIAN JOHNSON (2005’s Brick) I had been to Park City when my student short, Evil Demon Golf Ball From Hell!!!, played Slamdance, and I went without a place to stay. Someone was doing an event in the basement of a cookie factory on Main Street, so they set up these tents with little TVs inside. I was too socially inept to make friends and find a place to crash, so I snuck in and slept in one of the tents.

LIN I had to take out a loan to go, and it was not a favorable loan. We rented a cabin on the outskirts of Park City and I told everyone to bring a sleeping bag. Thirty of us jammed inside. I bought spaghetti, and that’s what we ate every night.

ARONOFSKY We printed a banner with the pi symbol on it because the one thing we had figured out was marketing by splashing Pi everywhere. We had been putting stickers and graffiti all over New York.

BILL CONDON (1998’s Gods and Monsters, 2025’s Kiss of the Spider Woman)Our joke was always, “Here come the Pi people, again.” Pi had made up these black skullcaps. It felt like you couldn’t go anywhere without a Pi person.

DANIEL KWAN (The Daniels’ Swiss Army Man) It was a hard week, if I’m being honest. In some ways, we pulled a prank on the audience in a way that was pretty thrilling, but it didn’t come without consequences.

ZHAO Ryan Coogler and I were staying at the resort. It’s so cold there, and Ryan didn’t know how to make a fire in his room, so I was trying to teach him how to make a fire.

NICOLE HOLOFCENER (1995’s Walking and Talking) Our plane had to turn back because a bird flew into the windshield. Ted Hope and James Schamus rented a private plane. I don’t know how — it was thousands and thousands of dollars. It was very small, and we were in a snowstorm, as if the festival was more important than our lives. I took a fat Valium and sat there on this tiny plane. We were late to the screening and rushed with the [film cans] to the Egyptian. I want to say it was Todd Solondz who was entertaining the crowd, because he had Welcome to the Dollhouse there.

LULU WANG (2019’s The Farewell) The producers rented a house for a bunch of us, and Barry [Jenkins], my then-boyfriend and now husband, came. My parents came with a bunch of my friends from college who don’t do anything in the film business. I remember saying, “I don’t think a wedding could be better than this.” I had a wedding last year, and I loved the wedding, but I was right.

HEDER When I arrived the first time, it was with a three-month-old baby and a two-year-old, so I did not have the filmmaker experience I dreamt about: being wasted at parties and running through the snow with filmmakers. I was pumping breast milk in bathrooms in between junkets and running milk up and down Main Street. Elliot Page and I would be in the bathroom together, and I would hand him the milk underneath the stall. He would say, “Pretty good haul.” Then we would run down Main Street having snowball fights on the way.

HELLER I traveled with my five-week-old, barely able to walk, truthfully, after having an emergency C-section. All of my family and friends came to help because I was so stressed and scared. I was breastfeeding at the opening-night party and pumping while I got my makeup done. When I was with Alexander Skarsgard doing press, my husband had the baby in a Bjorn just around the corner in a coffee shop, so I could always pop in and nurse him. It’s much more common now, but I was really adamant to not hide the fact that I just had a baby. I was really vocal because I wanted to show what being a female filmmaker looked like.

LONERGAN Sixteen bitter, happy years after You Can Count on Me, I went back with Manchester by the Sea. I was happy with it, but the subject matter was so painful. Matt Damon, Casey Affleck and the whole cast were there. Kimberly Steward, our producer — it was her first movie and she financed the whole thing and flew everybody out. Not just the big shots but everyone including the supporting cast and anybody who had a substantial role in an incredible act of generosity. It’s a golden rule of show business that if you’re doing well, someone else’s feelings are getting hurt. If your feelings are hurt, someone else is having a great day. That’s never not the case. You can’t win without somebody else losing. It’s a terrible ironclad law of balance and imbalance. What happens at festivals is that you’ll be having a great time, but they won’t pay for your friend to come. Or they’ll offer your movie star a nice hotel room and a plane ticket but your non movie star friend has to pay their own way. You think to yourself, well, this is a fucking shit hole and a shitty way to behave. It’s always a bunch of assholes throwing money around and they can afford a ticket for the friend. What an ugly way to live. Kimberly was so eager to include everybody — and I don’t think it was cheap — but it wouldn’t be prohibitive for other people to do the same. She put us in a suite that was so immense that I was almost embarrassed but not quite because I’d been around for 16 years by that point so I was committed to enjoy it.

CONDON I got on an elevator and there was Parker Posey, who was the poster child for Sundance. I actually said, “Oh my God. I’m really here. It’s Parker Posey.” She laughed.

THE ANXIETY-INDUCING WORLD PREMIERE

LINKLATER Slacker is a grungy movie, and that was the height of the Gen X grunge moment, so it fit the time. But a funny thing happened on the way to Sundance: War broke out in Iraq. All my dark, edgy jokes about terrorism and blowing stuff up weren’t getting laughs. There was a pall over the audience during the first screening at the Egyptian. After the movie ended, my producer’s rep, John Pierson, confirmed, “That was not a good screening.” We’d had nothing but good screenings over the past year, so I knew I was in trouble. The first question we got during the Q&A was about the short film that ran before my film, Alison Maclean’s Kitchen Sink, which was a really good film. But if they don’t ask about yours right away, it’s not a good sign. Everyone reads about triumphant Sundance stories and how great it went from the beginning. But my first screening did not go well.

Fred Hayes/Getty Images

ARONOFSKY The Pi premiere was a fiasco. The film ripped three times on the first reel, so we got 15 minutes in, and they had to start over. During the Q&A, nobody asked any questions. My friend Scott Silver, a filmmaker who did Johns, came to support me and raised his hand to get it going. He did me a solid, and I answered his question. There weren’t any more after that. It was a disaster.

MARC FORSTER (2000’s Everything Put Together) When you go and share a movie, you think of every scenario what could go wrong, and you really don’t think about what actually could go right. It was the first [screening] with an audience, and you could hear a pin drop. You felt the audience was glued to the screen.

KWAN We intentionally kept the details of [Swiss Army Man] pretty vague and presented it as a typical Sundance drama about survival with these two great lead actors [Daniel Radcliffe and Paul Dano]. None of that was a lie, but we wanted to see what would happen if people went into the screening and we pulled the rug out. Some people who attended the premiere later told us it was one of the most thrilling experiences they’ve ever had in a theater because they had absolutely no idea what was happening. But not everyone.

FIELD The first screening was at The Library. I went to speak to the projectionist, who wasn’t a nice man. I had worked as a projectionist, so I knew what I was talking about. It was shot [on 35mm film], and I wanted to make sure technically that it was all set up. He wasn’t having it and was very dismissive, like, “Yeah, yeah, I got it.” The first 10 minutes of the movie started, and of course it was out of focus. I was sweating and nervous and panicking.

LIN Our world premiere was at the Eccles, a huge theater. I was completely numb and shaking so much. I couldn’t actually stay and watch the movie, so I went to the lobby with our publicist when critic Kenneth Turan walked out saying, “I don’t do high school movies.” I remember thinking, “Oh my God, we’re dead. We’re dead. The L.A. Times just walked out.”

JANICZA BRAVO (2017’s Lemon, 2020’s Zola) I remember when [New York Times critic] Manohla Dargis was [at the Lemon premiere], and she hated it. [Laughs.] I remember a lot of people not liking it. It didn’t feel as good as I thought it would feel. The audience reception kind of felt a little bit off, and that didn’t feel very nice. But it’s this sort of really great lesson: Who are you making the work for? The positive is that the movie allowed me to get my second feature.

LONERGAN The premiere of [You Can Count of Me] was at the Eccles on Friday night. It was the first time I’d seen the film on a big screen in a big theater with a full house. I could feel that the audience was in tune, and it felt like a jolly, happy night. Sundance showed it four more times, and I learned something very interesting that I did not know coming from theater. In theater, you may have a good show but not a great audience, or not a great show but a good audience. Our second screening was in the morning, and it was full, but the audience was quiet. The movie is not a comedy, but it has laughs. At the morning screening, we didn’t get a laugh for 15 minutes. There was literally not a scintilla of difference in the film, but every audience brings their own dynamic regardless of what they’re watching.

BURNS Geoff Gilmore was running the festival, and he invited me onstage for the Q&A. At the end, he said that if anybody wanted to talk to the filmmaker, they should line up on the left side of the theater. The theater cleared out and — I’m not joking — there were between 75 and 100 people in line, all agents, managers, distributors. They handed me business cards and said they wanted to take a meeting in L.A. When I got home to New York, I checked the cards against my rejection letters to weed out who I wouldn’t sign with.

HARDWICKE The premiere was at the Eccles on Friday night. It was a packed, sold-out crowd, and Nikki and I held hands the entire time. We were gripping so tightly that the blood was getting cut off and our hands almost turned purple. At the end, people seemed very moved and were in tears. It’s a scary, heavy movie, and it got an incredibly positive reaction. Evan Rachel Wood, Nikki, Holly Hunter and Brady Corbet, who was 14 at the time — we were all up onstage just in shock.

HOLOFCENER We screened [Walking and Talking], and it was a dream come true with an incredible reception. Brooke Shields came up and said, “I loved this movie.” I felt anointed.

KUSAMA We didn’t have any money for a real screening while we were making it, so the world premiere at The Library was the first time I had seen the film with an audience. It was absolutely out-of-body for me. Even now, I can’t process it because I’m not necessarily designed for that kind of attention. Joel Cohen and Frances McDormand sat in the row in front of me. When the movie ended, Fran stood up, turned around and said, “Good job, kid.”

BREWER Before the world premiere, I pulled Taraji P. Henson and Terrence Howard into the bathroom and said, “Here’s what we’re going to do. To get everybody in the mood, I’m going to do the Ike Turner part of ‘Proud Mary.’ And then Taraji and Terrence, I want you to do the Tina Turner part.” So we walked onstage to introduce the film, and I asked how many people were from Park City. A few people wooed. I said, “How many people have 323, 310 or 818 in their area codes?” Everybody applauded, so I said, “I’m a little bit worried that we’re not going to get the Southern thing, so start snapping your fingers.” We launched into “left a good job in the city, workin’ for the man every night and day.” We did a verse and everybody applauded. “Enjoy the movie, everybody,” I said. When the movie was over, people rushed out to start negotiations, and we were told that we added an extra million dollars to the price.

KWANOur first screening [of Swiss Army Man] was at the Eccles. They oversold tickets and turned people away while others were sitting on the floor, which wasn’t allowed due to fire codes. It was chaotic, and they had to start the movie late, which everyone knows can be catastrophic at a festival. Once the screening started, people started to leave to make their next movie and others left because they thought since Daniel Radcliffe was in the movie, it would be like Harry Potter. There were kids in the audience. But our movie is an R-rated farting corpse dramedy about mortality, friendship, all these things. I left the theater thinking it was really fun and exciting. But I looked at Twitter and [entertainment journalist] Jeff Sneider tweeted that the screening was a complete train wreck. Because he left early and posted that before anyone else, his was the first reaction out of the movie — all because he was pissed that the movie started late. He didn’t like the movie, which is totally fair and I don’t hold that against him. But because his reaction was first, it became all these headlines about what a disaster it was.

GREENFIELD Jackie Siegel came to Sundance, did the red carpet and blew kisses to the audience afterward. She even went to a fundraising party for Sundance and met Robert Redford, who introduced our film on opening night. The Siegels were loving it, soaking up all the attention at the same time she and her husband were suing the festival and us.

BRAFF At the world premiere [of Garden State] at the Eccles, I looked out at the audience, and it was insane. It was everything I dreamed about, all happening at such a young age. I introduced the movie and went to the back of the theater. As the lights went down, I started to cry — not just tears but really sobbing. Anybody who has made a movie can relate to the sprint and how hard it is to finish. Every day there are new stresses, and it’s up and down the entire way. When the lights went down, my body had this reaction, “Oh my God, I fucking did it.” And tears just rolled down my face.

DUVERNAY At our second screening [of Middle of Nowhere] at the Eccles, a woman stood up in the audience and said that she had been waiting on me and that I made her proud. That woman was Julie Dash — the great filmmaker of Daughters of the Dust, who had been at the festival a decade and a half before — my cinematic hero.

ZHAO The premiere was beautiful because half of the room were either colleagues, friends or cast and crew. I felt less nervous than I thought I would because it was so in community, and I felt very safe. It didn’t feel like the kind of nerve-racking world premiere experience people usually have. I had that with my later films, but the first one was easier because I felt very held at Sundance. Things always get rocky the deeper you sail into the waters.

COOGLER The world premiere is my favorite memory. We had so many people that meant so much to me. Oscar Grant’s family was there [Fruitvale Station chronicles the 2009 killing of 22-year-old Grant by Bay Area Rapid Transit police]. Michelle Satter told me she was proud of me. I remember that vividly. She don’t bullshit, bro — she don’t lie. She said, “I’m so proud of you.”

SMITH Geoff Gilmore introduced me with words I still carry in my heart: “If Kevin Smith didn’t exist, Sundance would have had to invent him.” For somebody who dreamed about being accepted into that world, to hear those words, it did not matter if we got distribution, it was the validation of that whole community.

PARK The movie ended and people were clapping. I realized everyone was standing up. You read about crazy standing ovations lasting for 30 minutes in Venice or Cannes, but this was totally surreal for Sundance. We walked to the Eccles parking lot, where there was an SUV waiting. We called [producer] Margot Robbie on speakerphone and told her what happened. [Producer] Tom [Ackerley] said, “Wow, your films really get inside people’s hearts, and it was really beautiful to see.” I’ll never forget hearing that while snow was falling in the dark of night.

CONDON For Gods and Monsters, we had one screening in Salt Lake City. I’m not saying it was a Mormon audience, but it felt conservative. Obviously, it’s an audience that loves movies too. But many of the laughs make you complicit with Ian McKellen, who’s trying to get the beautiful, young Brendan Fraser out of his clothes. I got the feeling there were some people in that audience who in real life would certainly disapprove, if not stone, the elder gay who’s hitting on the young guy.

KUSAMA I thought I was getting some attention, but [Girlfight breakout star] Michelle Rodriguez was next to me and getting the most insane amount. There were actors, directors, agents, everyone coming up to her. Because it was her first role, I was aware of the crush of disorienting attention that was going to come her way and an almost a false sense of urgency to make a decision and figure out her next move. It’s so Hollywood, honestly. I just wish we could’ve protected her from it a little bit more. Success is always a mixed bag.

Chris Polk/FilmMagic

LONERGAN The premiere of Manchester by the Sea was a blur. Matt Damon, the producer and instigator of the whole thing, was there. I was nervous and not sure if people would go for the movie. I made Casey Affleck sit through the screening and watch it even though he doesn’t like to watch himself. Of course he said he didn’t like himself but he thought the movie was great. I said, “You’re just an asshole, but I can’t help that.” I went onstage after and was overwhelmed with all the lights in my face. Apparently everyone was on their feet giving it a standing ovation, but I hadn’t really noticed. I’d been through some real fucking hell the previous years, so I felt like I had at least earned the right to enjoy myself. I won’t go so far as to say I’d earned the experience, but having had the experience, I felt allowed to enjoy it.

HEDERCODA premiered online during the pandemic, and it created such an incredible democratization. I was getting texts from people I went to high school with, my parents’ friends and the fishermen whose boats we used for filming. Everyone got to go to Sundance that year. Otherwise, while it’s great to be there, run down Main Street and do all the press and parties, it can be a very elitist experience in the sense that there’s only so many people who can afford to travel and rent a condo. I got to share that year with my kids, who were 4 and 6. It was so intimate and lovely. Kids are riveted by CODA because sign language is interesting to them. Of course, they learned how to say “fuck” in sign language, and that was the best thing ever for a 6-year-old.

HEATED RIVALRY: FAKE BIDDING WARS AND BITTER NEGOTIATIONS

FIELD There was interest [from distributors], but I was so new and didn’t make it easy. In the Bedroom was not the type of movie that people were into at the time, but Peter Rice at Searchlight was interested, and I remember saying, “Peter Rice, you don’t want this movie. Don’t buy it.” I wasn’t allowed to sit in any meetings after that.

ARONOFSKY Our second screening of Pi was at the Eccles, and we got a standing ovation. Lindsay Law from Fox Searchlight, a beautiful guy who was a great father of independent film, said he would make a fake offer to start a bidding war. He was a mensch to do that, and it meant LIVE Entertainment, which became Artisan, was negotiating against themselves, but they didn’t know it. We had a meal with Artisan’s Amir Malin and Bill Block, and Amir insulted my film to my face and gave a very low offer. I walked out, but my attorney at the time, Jeremy Barber, now a partner at UTA, saved the deal. I still don’t know what he did, but he worked some magic and made a deal [reportedly worth $1 million].

LONERGANI got scale for writing and directing You Can Count on Me, which is what you get for indies. I got a piece of the sale, but Shooting Gallery, which co-financed the movie, went bankrupt, owing $5 million to various people. The guy who ran the company [chairman Larry Meistrich] had taken a lot of people’s money and never paid it back. I ended up being owed $200,000. I had made a very good living as a screenwriter, and my job prospects were better than ever. I wanted to get my money, but on the other hand, I would be an idiot to feel bad. I ran into him at a restaurant years later and said, “Hey, Larry.” He said, “Hey.” As I walked past him, I said, “That motherfucker owes me $200,000.”

KWAN It was crickets [after the Swiss Army Man premiere]. Nobody put in any offers. It was a really hard few days, and people were talking about it only in a very negative way. I went on walks in the snow with my wife in the dark and would say, “What are we doing?” But we still had screenings to go to, and they were all sold out. It was a few days after the premiere, and an older gentleman approached me in a theater after a Q&A. He said he came in curious because everyone was talking about how absurd it was and blah, blah, blah. But he said, “I had no idea that it was going to be this really moving experience.” He pointed at us and said, “You cannot allow journalists to take the narrative from you. All the headlines are saying one thing — do not let them write the story of what your movie is about. Push back and rewrite it.” That man lit a fire under my ass. We reclaimed the movie and sold to A24 the second half of that week, and we won best director. So the Sundance experience had its own three-act structure in the middle of the mountains and snow at a high altitude. And Jeff Sneider also lost his job that week, which is wild.

FIELD Harvey Weinstein wasn’t there that year [he reportedly was banned from attending because of an altercation the previous year], but his team [including Mark Gill] really wanted the movie and made a deal that Harvey wasn’t happy about. I was crying, screaming, about to throw up because I had heard how he would force cuts and take control of the movie.

SMITH By the time we got to the last [Clerks] screening at the Egyptian, that was our biggest screening on the biggest screen they had in those days. Unfortunately, kids, in order to tell the story, I have to say the name, but [Miramax acquisitions exec] Mark Tusk was like, “I’m going to deliver Harvey Weinstein to the screening.” We had a screening at Miramax in November, and Harvey walked out 20 minutes into the movie and showed no interest. We thought we were done but after all the buzz, Mark said, “I’m going to bring him back.” The screening was — as they used to say in the ‘90s — off the hook. Afterward we ran across the street to the Eating Establishment and there was Harvey Weinstein, smoking cigarettes, eating potato skins and talking about the movie. He said, “That’s a great fucking movie. It’s a funny fucking movie. I’m going to take that fucking movie and put it in fucking theaters all across the country.” My producer Scott Mosier and I were like, “Fucking A.” He made a deal with [our rep] John Pierson and David Linde, who went on to run Universal but at the time was the Miramax lawyer. Harvey left, and we sat there with David Linde while he wrote the deal on a yellow legal pad. While he was writing, blood dripped from his nose onto the pad. Scott was like, “Well, that’s foreboding.”

BRAFF It’s controversial to say the name now, but you can’t tell the Sundance story without Harvey Weinstein. He was blowing up everybody’s phones trying to buy the movie. He was the elephant in the room. If he didn’t like your film, it really hurt you because other bidders would say, “Why doesn’t he want it? Maybe we shouldn’t either.” It was really scary. It was a mob boss vibe in the way he permeated the town. When he and Miramax came in to bid on Garden State, it had the opposite effect and everyone wanted to get involved. Peter Rice was the man. He was the coolest guy there was, and his era at Searchlight was amazing. And suddenly, he and Harvey were fighting over the movie. Nothing happened the first night, but the next night when we all sat down for dinner, the lawyers who were negotiating called to let us know it was going down at this small house off Main Street. We went there immediately but they wouldn’t let us in the room where they were hammering out the deal, so Gary and his lawyer sent us downstairs. Me, Pam Abdy, Danny DeVito, Rich Klubeck and my managers at the time, Keith Addis and Sandra Chang, all went downstairs and huddled in a laundry room in the basement. It was so surreal and not at all how I thought it would go down. They negotiated for a while until they decided to partner on it with Searchlight taking domestic and Miramax taking foreign.

FIELD I didn’t meet Harvey until months later. By that point, I think he had an idea of what to expect [from me] and I had an idea what to expect from him and how to play it because I had gotten advice on how to navigate that situation. [Field previously told The New Yorker that he turned to longtime friend and Eyes Wide Shut co-star Tom Cruise for advice on Weinstein. Cruise suggested he not give Weinstein any pushback and allow him to make the edits but when it tested poorly with audiences, Field should remind them how well it played at fests like Sundance so they’d release the original.]

LIN Ruth Vitale at Paramount Classics hated my movie. She walked out of the screening and I guess she wanted to stick it to somebody, I’m not sure who, so she said, “Over my dead body.” She made sure to say it loud enough for me to hear. It’s funny because we ended up going with Paramount and MTV Films. It wasn’t a huge purchase, but enough. I decided to take the number and divide it into equal shares so that everyone who worked on the film got something. They deserved it because they worked for free and it wasn’t right for me to say “thank you” and take the money for myself. It was the right call. But it wasn’t until I did my first studio film that I got a call [from my business manager] saying that I was finally out of debt and had hit zero.

PEIRCE Christine Vachon called from Sundance a week later, in the morning. They’d been up all night. They’d sold Boys Don’t Cry in a bidding war to Fox Searchlight, the company Tom Rothman had talked to us about at the lab, the company that was made to make and release movies like the ones we would make. Christine, John Hart, Jeff Sharp of IFC and John Sloss, my lawyer who brokered the deal, had sold Boys Don’t Cry at the Sundance Film Festival to Lindsey Law, Peter Rice and the now late Michael Stremmel of Fox Searchlight as a negative pickup for $5 million. The highest sale of an unfinished movie in an editing bay at that point. That sale made it possible to finish the film properly. To give it the release it deserved. That’s the cultural impact of Sundance: Sundance protects stories that would otherwise be erased or would never come to be — and then those stories change what the culture can see and feel. Pretty extraordinary. My dream was to open Boys Don’t Cry at Sundance because the labs helped bring it to life and the festival is where we got the life support to keep it going. But we couldn’t because of when we finished — late September 1999 — and because we got into Venice, Toronto and the New York Film Festival and had to use those festivals to open and launch the movie to open in theaters Oct. 8, 1999.

GREENFIELDThe Queen of Versailles was a very hard film to finance because it was about rich people, and people didn’t want to see a story about rich people unless, as someone said, “they end up homeless.” But I believed in the story because I had been photographing the economic crash of 2008 all over the world. I’d seen the impact from plumbers to electricians, from Lake Elsinore to Dubai, from Ireland to Iceland. I watched how it hit every level of the working class. In order to finish it, we had to take a home equity loan out on our house. If we hadn’t sold it at Sundance, we would’ve lost our house, which would’ve been very ironic. We sold it at about 3 a.m. to Magnolia, and they were very brave amid the threat of a lawsuit. Our lawyer, Linda Lichter, took the lead and we were honestly so happy to have a home for our movie and to keep our home.

JOHNSON [About reports that Brick, which was made for $450,000, sold for $2 million to Focus Features] My cellphone had literally been shut off the previous month because I couldn’t pay the bill. I was borrowing money from my producer just to pay rent. Selling the film was a huge relief because we had done the Blood Simple thing by financing the movie with private money by borrowing from friends and family. Knowing that I would be able to pay my grandfather, my father and my uncle back was an emotional relief.

BREWER Miramax offered $10 million but John Singleton was like, “Nah.” The negotiations went on and on and on. John really wanted Paramount because he knew MTV Films was based there and he felt it was the best place for the music. This was brilliant of him, but he made two prints of it, so while one showed at Sundance, the other showed weeks before for Brad Grey who had just become CEO. Brad was getting updates from Ruth Vitale at Paramount Classics and he said, “Get that movie.” So John did what I call the Elvis Presley comeback deal. Elvis was supposed to get a million dollars for this movie in 1968 with Mary Tyler Moore. Universal didn’t want to pay him a million since his last three films had bombed. So, [his manager] the Colonel said, “How about you give us $1.25 million and for that, he will do the movie and a Christmas special for NBC.” That’s what John did when the offers came to $10 million. John told Paramount he would take $9 million but they had to give him what he should’ve gotten in the first place. He wanted a deal to make two movies at Paramount with no questions asked if the budget was $3.5 million with an ownership arrangement. John wanted to make his money back and get some respect for being the only guy at the party who put his own money into Hustle & Flow when everybody else said no. I learned a lot, sometimes painfully, about business from John.

WANG I went to bed and left my phone on like they instructed, and it started ringing at 11 p.m. They were like, “You need to get dressed. We’re sending a car to pick you up.” They sent a black car and I was in sweatpants. They drove me to a mansion with a private chef. They said, “Oh, do you want any food? They’ll cook you food!” It was really strange. There were chairs set up in a circle and every potential distributor came and pitched me. I’d spent a decade pitching other people, and suddenly they were pitching me. There was a last-minute dark horse — I can now say it was Netflix — that came in with a lot more money. It became a big conversation I had to have with the producers. If we went with Netflix, it would be more than double the money, but I felt that because I wasn’t an established filmmaker, I needed theatrical to establish myself.

BENTLEY When we were selling Jockey it was during COVID. Greg [Kwedar, filmmaking partner] had come to Dallas, and it was a couple of nights before our premiere. It was Friday night, and we were like, nothing’s going to happen tonight. We were watching movies, and we figured we should take gummies while we watched. Halfway through a movie, one of our phones was blowing up. It was because Sony Classics was trying to buy the film. I had to go downstairs and wake up my wife and say, “You have to make sure we don’t make a terrible decision. I’m willing to say ‘yes’ to anything right now.”

HEDER After CODA’s screening, I met with Apple, Amazon and a bunch of others. I already had a relationship with Apple because I had made Little America with them so I had good feelings, but ultimately the decision lay in the hands of my producers. Jamie Erlicht said to me, “I don’t think this is a movie. I think it’s a movement.” That really struck me because it meant they could see the potential of the film not only to reach audiences but to create a cultural shift. I was on the phone during negotiations and the number kept going up. I fell asleep at 3 a.m. with the phone next to my head. When I woke up, I discovered that Apple had won. [In a historic deal, Apple paid $25 million for worldwide distribution rights.] I ran into my old landlord when I got back from Sundance and she screamed at me from the street, “Oh my God! You have $25 million!” I was like, “Not me, lady, not me.” There was a moment when I felt like I should be more a part of this waterfall than I am.

THE SCENE BEYOND THE SCREEN

ARONOFSKY When I was on the jury, someone came up and said, “Take a picture with Paris.” I was like, OK, but had no idea who she was. I agreed and somewhere out there is a photo of me with Paris Hilton. This was before Sundance had become a party spot, and years later when I went back I would stand in these lines, like, why am I trying to get into this party? The films were still fantastic, but it was a whole different experience.

J. Vespa/WireImage

JOHNSON It’s hard to communicate just how Fellini-esque the experience is, especially for first-time filmmakers who have never been anywhere or done anything. For me, it was a little bit like being Luke coming from Tatooine and suddenly getting a medal in the Rebel base. It was bizarre but wonderful.

LINKLATER There wasn’t a lot of press back in the day. Maybe one reporter from the L.A. Times, TheNew York Times and the trades. I did one interview the entire time for Slacker, and it was a grouped interview with a bunch of filmmakers. The good thing about that is I was able to see a bunch of films and go to parties. I saw three or four films a day and met a bunch of filmmakers, some I’m still friends with. Todd Haynes had Poison and ended up winning. Gus Van Sant was on the jury and I met him. He came up to me after a screening of Slacker with a little grin on his face. After we talked, he whispered in my ear, “You got my vote.” That’s probably something you shouldn’t do as a juror because it had me thinking, well, there are four jurors and I already got one vote. Now we only need one more vote, maybe two.

HARDWICKE I had to watch out for Nikki [Reed] as her chaperone. She looked 18, and people could not believe she was only 14. The second half of the festival people were hitting on her left and right as we walked down Main Street. I had to say, “No! She’s 14!” I started making announcements during the Q&As right at the beginning to say that “Evan Rachel Wood and Nikki Reed are only 14 years old. Don’t even think about it!” They look sophisticated in the movie and because Hollywood has a history of casting 18- or 21-year-olds to play young teenagers or high school students, it confused people. But I went for the real deal and cast actors who were actually 13. That was mind-blowing for people.

LIN Our third screening was at The Library. The entire Q&A was flat, which was my fault because of lack of sleep or I didn’t feel good. It came to the last question and I pointed to this guy who stood up and said, “You know how to make a movie but why with the talent up there and yourself did you make a film so empty and amoral for Asian Americans and for Americans?” Before I could answer, someone jumped up to go after him. Pretty soon, it was out of control and people were going off. It was chaos. Out of nowhere Roger Ebert stood on his seat and defended the movie by saying that nobody would say to a bunch of white filmmakers, “How could you do this to your people?” He said Asian American characters have a right to be whoever the hell they want to be. He put everything in context and to this day, I really appreciate that. They were trying to clear the theater because 30 minutes had passed and it was still chaos. People wouldn’t leave. Before that, we were just one of the little movies and that incident woke up something. It breathed life into the whole experience.

LONERGAN There was a press circuit that I’d never done before. I had done press for plays, but it was hilarious in Sundance because it was all done in a hotel room. You go from table to table and everyone asks questions about your movie and hopefully they say nice things. You quickly realize that you’re asked the same questions over and over. It felt like an old fashioned ‘50s movie when the dad goes off to a shoe salesman convention. I worked really hard on the movie for nine months of solid directorial work so I felt like I deserved to have some fun, which is not something I often feel ready to jump into. But the weather was beautiful and snowy and I had a nice sweater and we were all wearing sweaters and snow boots. I was there with my best friend, Matthew Broderick, and I love Mark and Laura so it was a jolly, affectionate group. It was a big party scene, and I still liked going to parties then. It’s hard not to have fun when your movie premieres in a big theater and everybody loves it and people tell you how great you are for a week and a half straight and they ask questions as if they’re interested in you. It’s tough to be sad under those circumstances. If you’re able to lean in, you can enjoy it without deciding that you’ve become the center of everybody else’s universe. At the time, I felt slightly as if you’re not supposed to have fun with the glitzy side of show business because it’s morally wrong.

Fred Hayes/WireImage

BREWER After the sale of Hustle & Flow, we’re all in our house partying. We were drunk, stoned and blasting Memphis rap. I got a call from Charles King, who now runs MACRO but was my new agent at the time, to invite me to the William Morris party. I said, “Well, I’m kind of partying.” He said, “No, you just had the biggest sale at Sundance, you have to come.” I told him I was with friends but he said, “Bring them.” We marched down the street to get to the party when we passed this really long, thick line of celebrities and people waiting to get in. I heard someone say, “Mr. Brewer, right this way. Come to the front.” I went to the front and it was a guy that worked for Charles King. “I hear you have a friend with you,” he said. I told him no, I have friends with me not just one. He turned around to see 20 fucking people behind me and his face turned white. Kevin Bacon and all these people were waiting to get in. He let us all in and all these Memphis people burst into the party. It was surreal.

LINKLATER I’ve always thought that a fun joint project we should all do together is a documentary called Sick at Sundance. By the time you got off the plane, you or someone in your party gets the winter flu. I don’t get sick very much, but one year we were doing a 20th anniversary event for Slacker and I was on death’s door in my room. I could barely make it out. I did the Q&A sick as a dog.

BRAVO The night before [Zola] premiered, I went to bed before midnight and was so proud of myself. I started to hear the lowest [coughs] in the next room, and it was Riley Keough, who got really sick around 2 a.m. I opened the door, and she was on her knees trying to quietly leave our house. I was like, “What’s happening with you?” She said, “I have to go to the emergency room.” We spent two hours in the ER, and they said it could’ve been the flu, though they weren’t sure. But it had to be COVID.

BRAFF There were lots and lots of photo shoots. I did one photo shoot with Peter Sarsgaard lying on fake snow and looking up a skunk’s butt. I’m sure the direction was not to look up its butt, but I thought it would be fun. Keep in mind, I was brand new to the business, and I’d never heard of a gifting suite. Peter was always very cool and he said, “I don’t need any of that.” But I was like, “Wait, people are giving away free shit? I’ll take it all.” I was so wide-eyed and geeked.

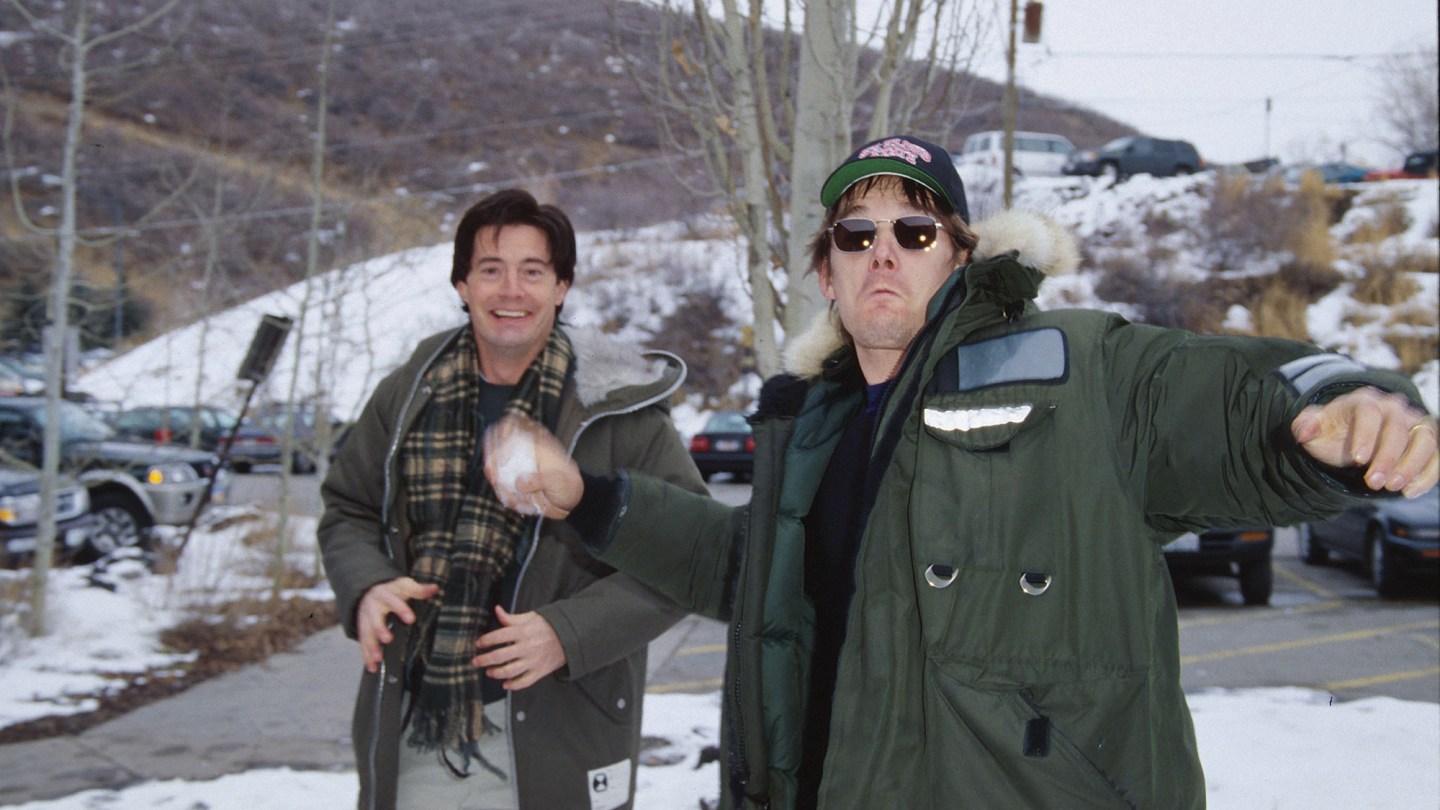

ARONOFSKY The first time I ever posed for a photograph for press was at the bottom of Main Street with three other directors. The photographer was standing 15 feet away, and we were directed to throw a snowball at him on the count of three. I was in such a state of unconsciousness about everything during the festival that I wasn’t thinking straight. I threw a snowball right at him. It hit his camera super hard and he started cursing me out. They all looked at me, like, “What the fuck are you doing?” I was so sorry and apologetic. I grew up playing Little League, so it didn’t occur to me to not throw it directly at him. It was such a weird moment.

LONERGAN In 2016, I felt like a semi-big shot who could say hello to anybody I wanted. Casey Affleck and I were at a restaurant and saw Werner Herzog in the bar with his wife and a few friends. Casey had met Werner before so we went over to say hello. Casey reminded him that they had had a meeting a few years prior by saying, “I met you at this park and your driver had gotten lost but we ended up going for a really nice walk and having a nice conversation.” Werner replied, “This is clearly a fantasy because I’ve never had a driver and I don’t have a driver now. This is an imagination.” He was pleasant but I never forgot him saying, “This is clearly a fantasy.” As Casey and I walked away, he said, “He had a fucking driver. Somebody drove him, maybe an assistant, but he wasn’t driving that car.”

PARK I was having lunch on Main Street with our producer Bronte Payne and she said, “This is a moment for you. You should use the heat to do something else.” I wanted to make a TV show in the young adult space, and there was a girl from Netflix sitting super close to us at the next table over. She and Bronte knew each other and she said, “Did you just say you’re doing a TV show? You should call me if you have a pitch.” I called my manager who said it was a fucking great idea to pitch a series, so on the heels of Sundance we took out my version of Dawson’s Creek [called Sterling Point] and it turned into an insane bidding war and we ended up at Amazon.

SAYLES We came again in 2000 to support and help sell Karyn Kusama’s Girlfight — which shared the grand jury prize and Karyn won best director — because we helped finance it and Maggie Renzi was one of the producers who helped negotiate with distributors. My sharpest memory of that year was of waiting in deep snow for a shuttle van to take me to a screening and looking down at a red puddle at my feet. The combination of altitude and cold made my nose start gushing blood.

LINKLATERWaking Life was a huge moment for me. It was the first indie digital animated film, and it was so low budget. We didn’t have a distributor, and we had a great response out of Sundance. Peter Rice at Searchlight saw it and liked it a lot, so they picked it up. That was a success story and felt like a triumph. There’s an appreciation for newness at Sundance. If you show something there that people haven’t seen, they will appreciate it. They’re not like, “What the fuck is this?” That’s what they come for. They want to see something that blows their minds.

KWAN Sundance is a pressure cooker that can be really thrilling but also really humbling. The epilogue to our story is that a few years later when we were touring the country with Everything Everywhere All at Once, we stopped in Chicago for a screening. When it was over, an older gentleman walked up and said, “Hey, I don’t know if you remember me but I was the guy who came up to you at a Swiss Army Man screening and told you how to defend your movie. I was excited then and I’m excited now to be here with you. You did it and proved everyone wrong.” It was a really sweet interaction that only happens at film festivals because those audiences are true diehard cinema fans. He changed the way I think about press now and I take that interaction with me into everything. It’s so much bigger than Swiss Army Man.

GREENFIELD Jackie Siegel ended up loving the film. She went on to promote it with me for two years. We went to film festivals and traveled the world to the U.K., Finland and Switzerland. By the way, we eventually won the lawsuit and the Siegels had to pay $750,000 in legal fees. The lawsuit got us so much publicity that in his New York Times review, A.O. Scott wrote something like “a lawsuit in America is the highest form of flattery.”

PAYNE By the time I went back five years later [with my first feature Citizen Ruth], there was already a huge change, man. There were so many more people. We had our drink coupons or whatever where we were encouraged to go hang out and meet one another. By the time I returned in ‘96, it was Harvey Weinstein and the hoards of people. It was a different vibe.

SMITH I was a judge in the year 2000 or something like that. That’s when Levi’s started showing up. That’s when you could walk away with a washer-dryer set.

ARONOFSKY I always heard there was a lot of swag, though I never got a free parka.

HARDWICKE It was such a rush. We were constantly getting our photos taken, doing Q&As and getting free jackets.

JOHNSON The crazy gifting houses and corporate activations made it all feel like a circus and so surreal. I had heard people griping about it, but I had nothing to compare it to. I thought it was kind of icky but at the same time, I was broke so, yeah, I took a pair of free jeans. I couldn’t cross my arms and stand on purity.

HOLOFCENER They were giving away [Nintendo] Game Boys and I had little twin boys. I got one, and I needed to acquire two. America Ferrara was there and she said, “I’m gonna get you your second Game Boy!” My kids were thrilled.

MARKDUPLASS (2003’s This Is John, 2005’s The Puffy Chair) We printed 1,000 business cards with our cellphones and email addresses on them. We pressed hundreds of DVDs of the short to hand out to people to maximize the whole thing.

JAY DUPLASS We rented a tiny Toyota Tercel and we drove 10 miles into Park City every day at the crack of dawn. We never missed one party that we got invited to. We never missed one party that we didn’t get invited to, even if it involved us just loitering outside.

LIN We left Park City and drove back to Los Angeles. We were just floating the whole way home. We spent a night in Las Vegas and had a little celebratory buffet with the $10 lobsters and steak dinner.

PAYNE I was on the jury in 2006. That was a really groovy experience. They called me to be on the dramatic jury and I said, “No, I’d prefer to be on the documentary jury,” because the films in general would be more watchable. A lot of beginning features are pretty grim, even at a great festival like Sundance. We had a phenomenal time on the doc jury. All I can say is probably what everybody else is saying: The more I went back over the years, the more out of control it was. It still served its noble function that Robert Redford had envisioned, even if it was kind of abused by distributors and Hollywood people. It’s almost like the festival didn’t change; other people changed it somehow just by their presence and how they used and manipulated it for commercial reasons, which they keep allowing because it’s helping independent filmmakers get distribution, even if there’s a sleaze-bag factor.

HARDWICKE Not everyone got the message about Nikki. It completely went off the rails, and even these older filmmakers tried to hit on her. They would say, “Bring her to the party.” I’m, like, “Dude. She’s 14! No!” I had to guard her, but she was ready to run off and have fun. That was the worst part for me. Some guys crossed the line. It was 2003, and I guess people thought they could get away with it since not a lot of people had been busted yet.

INSIDE THE AWARDS CEREMONY

LINKLATER There’s always been a collision of art and politics from the beginning. Michael Moore was nosing around in 1991, and he organized a big petition in response to the war in Iraq. The wonderful and the great John Sayles hosted the awards ceremony, funny as always. Michael Moore talked John into reading the petition at the ceremony. It said something like, “The people at Sundance demand an immediate end to this war.” I could see George Bush or Saddam Hussein going, oh wait, over there in the snowy area of the western mountains of the United States, they’re calling for an end to the war so let’s cut this short, guys. The moment got hissed down because the audience was really mixed. We were not a politically cohesive group that night, which I appreciated. I loved the passion in the air and that people cared. They care about movies, they care about life, they care about art and they get together and fun shit happens.

SAYLES Somebody fell through as emcee for the awards ceremony in 1991, and I was asked to do it; not my favorite kind of gig. Just before I went on, Michael Moore, Pam Yates and other filmmakers asked if I’d try to get the audience to issue a joint condemnation of the Gulf War, which was heating up. I said I felt we were dealing with a lot of white people in parkas with their minds on something totally different, but I’d at least ask if they even wanted to vote. They didn’t.

BURNS The night of the awards fell on my 27th birthday. The rumor was that we were going to get the audience award, but when we didn’t win that, it was like, “Well, hey, we sold our movie so we got nothing to complain about.” Then Sam Jackson got up to present a grand jury prize, and we won. My parents had flown in, and my mom loved Robert Redford. I said, “Mom, come on over here. I want you to meet somebody.” There’s no greater gift you can give your mom than 10 minutes with Bob Redford.

MANGOLD I was seated next to Ed Burns when Sam Jackson announced I had gotten the [directing] prize. I remember Ed and I turned to each other because I didn’t know what prize I had won, and it was unclear what any of us were winning until Ed got up and got the grand prize [for The Brothers McMullen]. Apparently the judges were wanting to do a kind of tie, and so that’s where the directing prizes came from.

ARONOFSKY At the awards ceremony, Paul Schrader fucked up my name. I still see Paul, which is wonderful. I saw him recently at a random party with 25-year-olds in New York. The big question is why either of us were there. At the awards, everyone was hitting me on the back and there was one agent who was trying to sign me and he was the only one giving me a standing ovation. I locked eyes with him as I walked up to the podium.

LONERGAN They were buzzing about Girlfight and they were buzzing about us and I was sure they were buzzing more about Girlfight than us, but it turned out they were buzzing about us equally. I won the screenwriting award and then the jury split and we tied for the grand jury prize with Girlfight. I wasn’t expecting that. Not because I didn’t think my movie was good, but because how well you do and how good your work is are not always correlated. It happens every year. Movies that are good don’t get attention, movies that are good do get attention, and even bad movies are celebrated or ignored completely. There’s no connection. I was just happy to be there, sell my movie, win a prize and go.

KUSAMA I was completely stunned [to win two awards]. Janet Maslin spoke for the jury and said that there was such a spirited conversation and appreciation for both films so they made the unusual decision to give the grand jury prize to both films. It’s cool to be part of breaking the rules.

DUVERNAY [DuVernay became the first Black woman to win Sundance’s best director award.] It did not have an effect on my business prospects. It had an effect on my confidence, and that is really what matters. The most tangible effect of it is that it changed how I felt about myself. I was 32. I was a publicist. I had never gone to film school. I was making films on the side, and to get in and to win, in my own mind, that was the degree.

BREWER At the ceremony, I met Noah Baumbach and Amy Adams who broke out in Junebug and won an award. I sat with Jay and Mark Duplass who had Puffy Chair there that year. The three of us were nobodies, and we sat at a table looking at all these big directors and movie stars. Just dorks talking about what kind of cameras we used to shoot our movies. What chip size was it? How did you do your sound?

JOHNSON Miranda July and I both got a special jury prize [for originality of vision] and we ran into each other backstage and toasted the awards. John C. Reilly was on the jury and gave me a fist bump. I was like, oh, John C. Reilly likes my movie. It was all overwhelming. I don’t know if relief is the right word, but it did make me feel as if I would be able to make another movie. Like, I think we got away with it and I can do this again.

HEDER The awards ceremony was on Zoom during the pandemic, and I watched from my garage office. We kept winning [for CODA], and I ran outside yelling to my husband, who was working in the yard. “We just won best ensemble!” He said, “Yay!” I ran back inside, watched another category and ran back out, “I just won best director!” Then, “We just won the grand jury prize!” He said, “Yay!” It was a totally surreal experience, yet so thrilling and heartbreaking because I couldn’t be with my cast. [Sundance programmers] Kim Yutani and John Nein then rang my doorbell. They brought a bottle of champagne and lined up four awards going up the steps to my house in Eagle Rock. We sat on the porch and drank champagne. It was a very sweet, very beautiful experience in the middle of lockdown.

KUSAMA After we won, I was too discombobulated to go to the afterparty. I asked the cast and crew to gather at our condo so I could make dinner. I walked across an empty, ice-streaked parking lot into the biggest grocery store in Park City, which was not very good at the time. I had to make do with all the ingredients I could find. We came back to a condo filled with people who had worked on the film or who appreciated it. There was such a warmth from the toes up that could only have been created by Sundance. I made the simplest spaghetti and meatballs dinner and had to settle for Parmesan in that green tube. To this day, I still think, “Oh, if only I’d been able to find real Parmesan and actual Italian tomatoes from Italy.” I flew back home and of course returned to even more sleet and snow in New York. After such a disorienting film festival or Hollywood experience, I went back to a communal household in Fort Greene where I lived at the time. It was burrito night again, and it felt very grounding and necessary to get back to the meat of my life. It served as a lesson for what I’ve hoped to maintain in my career even now: All the light can shine in your direction, but it’s meaningless if you don’t have a home to return to.

All interviews edited for length and clarity. Scott Feinberg contributed to this report.

For more news, reviews, video interviews and more from the Sundance Film Festival, visit The Hollywood Reporter’s Sundance hub.

This story appeared in the Jan. 15 issue of The Hollywood Reporter magazine. Click here to subscribe.