Stripped of its distinctive details, the first half of Joanna Natasegara’s new documentary The Disciple is the stuff of a Disney movie: Adrift young man fixates on a musical act, finds himself onstage with the act, finds himself at the center of one of the most talked-about albums ever recorded.

It’s a rags-to-riches story that one can easily imagine starring Mark Wahlberg. Heck, it’s already basically the plot of multiple Mark Wahlberg movies.

The Disciple

Great rags-to-riches story, questionable storytelling choices.

Stripped of its distinctive details, the second half of The Disciple is the stuff of one of those fraud-centric documentaries or miniseries that were in vogue five years ago — captivating because of the layers of betrayal, but somehow reassuring because most of the real victims were people too grotesquely wealthy to be sympathetic.

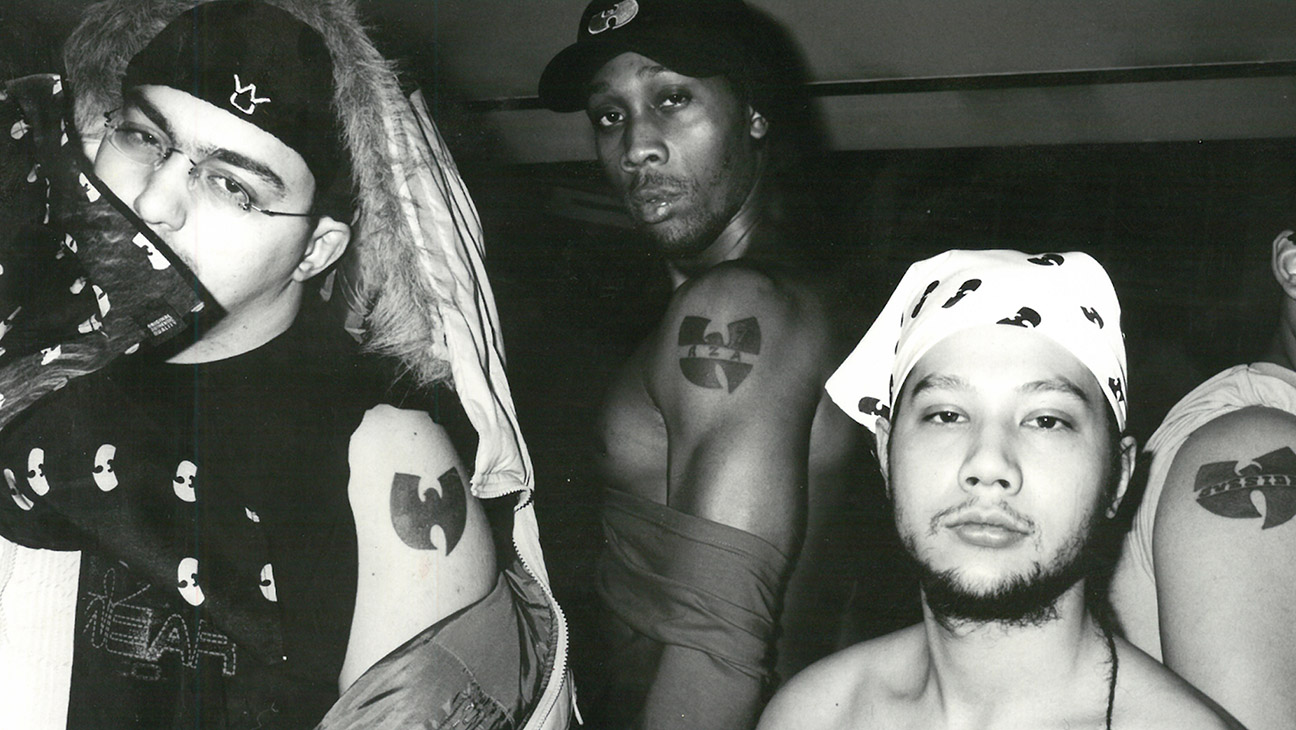

It’s a challenging combination of genres, one that Natasegara (Virunga) balances fairly well in The Disciple, which tells the story of Tarik “Cilvaringz” Azzougarh and the absurdly compelling saga of the Wu-Tang Clan‘s Once Upon a Time in Shaolin CD, also known as the one-printing-only disc purchased by Martin Shkreli for $2 million.

I found the documentary’s first half to be uplifting, fun and full of jaw-dropping details, benefitting from the extensive participation of Cilvaringz and the resources that come from having The RZA as an executive producer. But I found the open-ended pragmatism of the second half to be a little hollow and one-sided, as one might expect from a documentary made with the extensive participation of Cilvaringz and the resources that come from having The RZA as an executive producer.

Direct involvement of your documentary subjects: It’s a double-edged [liquid] sword!

Cilvaringz — that’s “Silver Rings” for the Wu-impaired — is the Holland-born son of Moroccan immigrants, who saw similarities in his upbringing to the world illustrated in the Wu-Tang Clan’s Enter the Wu-Tang (36 Chambers) and decided he was going to start his own unauthorized Wu-inspired ensemble, landing onstage with the Wu at a 1997 Amsterdam show. Cilvaringz eventually produced a compilation album that RZA unexpectedly decreed was a formal Wu-Tang Clan release, sparking the dissertation on capitalism and modern art that became the not-exactly-release of Once Upon a Time in Shaolin.

Cilvaringz, who admits he’s doing the documentary because he’s been accused of lots of stuff and he wants to get his side of the story out, is an interesting person, or at least he’s navigated his way into interesting circumstances. He had a traumatic childhood that he either discusses at a hazy remove, captured by Natasegara in dreamy, fragmentary flashbacks, or evasively treats as irrelevant.

He, instead, treats his own story as a tall tale. There’s video from a lot of it, including the amateur videos featuring his wannabe rap group and even the famed Amsterdam show, but if you didn’t know it was a true story, none of it would be believable. Natasegara heightens the reality with brief animated sequences, digitally weathered footage, and even unexpected and unexplained enhancement of certain interviews, like the actual Shaolin monk who talks to the camera in front of the backdrop of a dragon whose eyes come to life and survey the scene. Not all of Natasegara’s aesthetic choices are consistent or make sense, but she’s having fun.

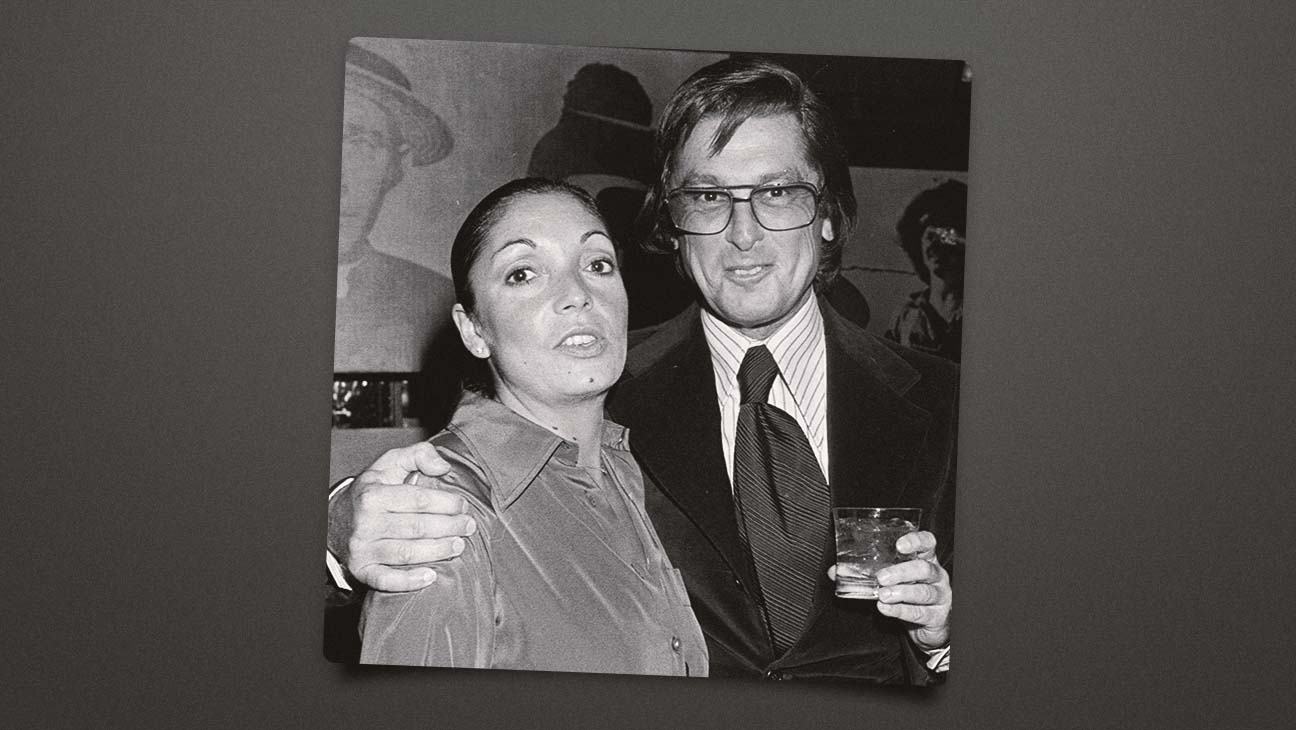

The larger-than-life aspect of the story carries over to the circumstances surrounding Once Upon a Time in Shaolin, where the cast of characters expands to include Cyrus Bozorgmehr and Alexander Gilkes, who all have Resting Fyre Festival Organizer Face, even if they profess general innocence in the public relations disaster that the album became. They’re talking to the camera, so we’re supposed to trust them, but with Shkreli, generally accepted as Satan incarnate, nowhere to be seen, they’re also the people who look shadiest. Cilvaringz talks a lot and takes the blame for certain strategic failures, but there’s a difference between saying a lot and coming across as transparent.

It isn’t that I wish Shkreli had appeared in the documentary — though perhaps if honey and fire ants were involved — but the absence of the rest of the Wu-Tang Clan is very, very telling. Even RZA, an executive producer, contributes only audio and a film send-off, and it’s unclear if those were filmed for the documentary. He doesn’t discuss any of the controversy around the album, which fell to him in part because he chose to slap the group’s name on a project that was recorded exclusively in non-collaborative bits and pieces. Method Man, who was particularly outspoken in distancing himself from every aspect of the project? Nowhere to be found.

The only primary Wu-Tang Clan member — Shabazz the Disciple, part of the affiliates collectively know as Killa Beez, is present — featured in the documentary is Cappadonna. Why Cappadonna? Haven’t the faintest. He’s mostly wandering around Staten Island having mini-reunions with old members of the neighborhood, shot in black and white. Why black and white? Haven’t the faintest. He’s pretty much in a different documentary, possibly outtakes from Sacha Jenkins’ generally superior and thoroughly better-populated four-parter Of Mics and Men.

The documentary is, finally, all about a displaced man who yearned for a community, found a place in one of the most exclusive communities in the world, and became an aspirational figure in some eyes and a pariah in others. The Disciple ends up a little wishy-washy in reflecting on where Cilvaringz’s story has resolved, but even a bland conclusion can’t blunt a good yarn.