Fashion and art — of the high, modern kind — are two industries that, time and time again on film, have proven beyond satire. The real entities are so frequently ridiculous, such vortices of money and ego, that any attempt to parody them easily seems superfluous, inexact.

Cathy Yan’s new film The Gallerist runs smack into this problem as it attempts to tell a mad, trenchant story about the modern art world’s seething cynicism, greed, and shallowness. What reads as fun on paper — Natalie Portman plays a desperate Miami gallery owner trying to pass off a dead body as conceptual art — is rendered clumsy and inert on screen.

The Gallerist

A limp piece of art about a limp piece of art.

The film begins amusingly enough. Portman is Paulina Polinski, a recent divorcée trying to establish herself as one of the great movers and shakers of the annual parade of fools looking to part with their money known as Art Basel. An unpleasant encounter with a loathsome influencer ends in his accidental death: He’s impaled on the sharp point of a sculpture created by the artist Paulina has chosen to champion, and upon whom the future of the gallery hinges. With the opening in a matter of minutes, Paulina makes a rash, only-in-the-movies decision: She’ll rearrange the body a little bit, replace the title card of the piece, and frame this gruesome display as searing commentary on masculinity…or something.

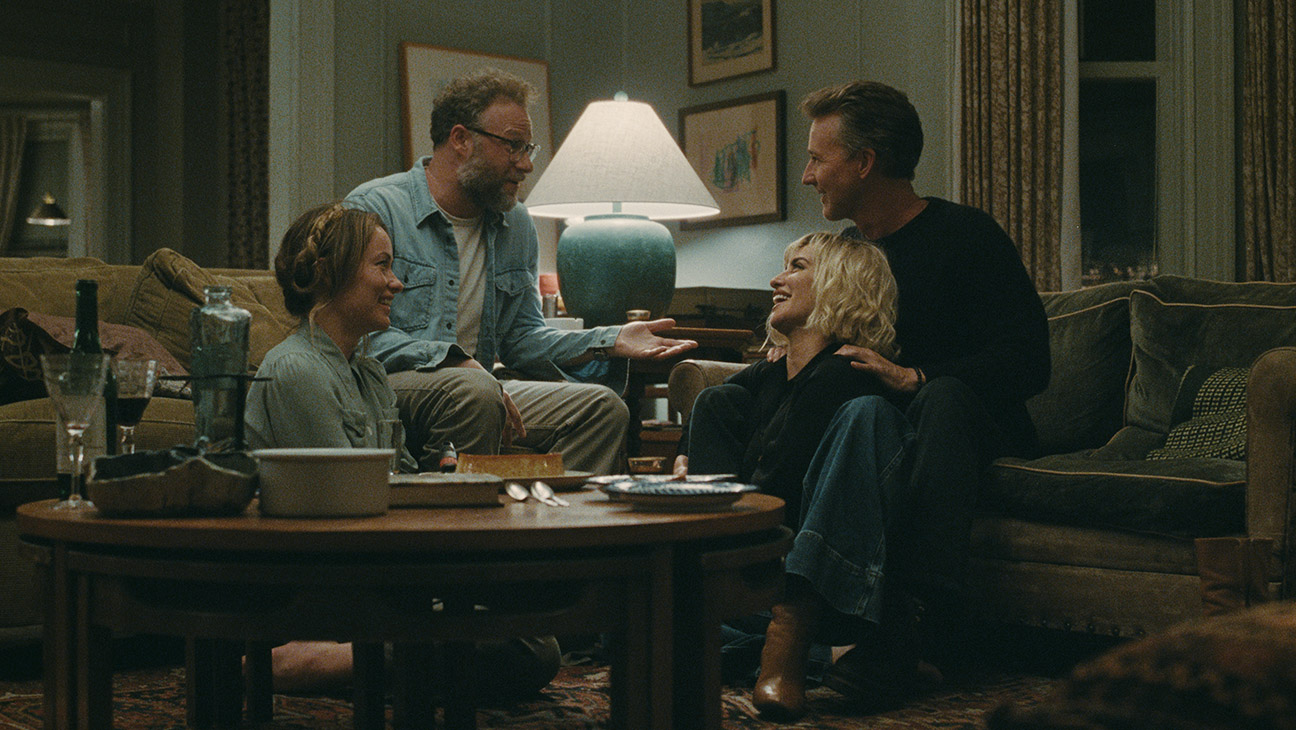

Buzzing around Paulina as she tries to keep things together are her neurotic assistant, Kiki (Jenna Ortega), the artist of the moment (Da’Vine Joy Randolph), and a sultry, hard-charging art dealer played by Catherine Zeta-Jones. The foursome scramble about trying to pass off the hoax, avoid arrest, and maybe make a lot of money in the process. Yan pitches her film as a high-comic thriller, her camera ceaselessly darting through the gallery space and tilting at odd angles as it pushes in on the worried, calculating faces of these women on the verge.

But the real desperation seems to be coming from behind the camera; as The Gallerist races along, the jokes start falling flat and the plot mechanics churn with a deafening creak. The film is only 88 minutes long, and yet it still runs out of story well before the end credits roll. By the time Sterling K. Brown (as Paulina’s dilettante ex-husband) and Daniel Bruhl (as a callow playboy trying to make a name as a collector) enter the picture, Yan seems to be grasping for an exit, anything that will get the film to some kind of satisfying conclusion.

The trouble is, it’s so unclear what, exactly, The Gallerist is trying to say that I have no idea what that conclusion would look like. Yes, yes, there are points being made about the state of the modern art market, but those have been made many times before, in various media. There is no argument specific to this film, only the broadest and most general critiques of an oft-critiqued industry. The film’s potential for interesting, particular discourse — particularly about Randolph’s character’s place in the food chain as a rising Black artist in a homogeneously-run world — is squandered as Yan spends most her time chasing the plot around.

The performances suffer from that distraction. I am an admiring fan of Natalie Portman’s big-swing, post-Black Swan work — I even like her in Lucy in the Sky — but here she struggles and fails to find traction. It’s vaguely apparent what she’s going for, a kind of haughty elitism thinly veiling howling insecurity, but she can’t find a way to make it credible, or even compelling. It’s all mannered tic, a naked and uncomfortable barrage of actor choices that she and Yan never sand down into something usable. When Portman shares a big scene with Brown, whose actorly energy can get illegible pretty quickly (see: American Fiction), it’s a clanging symphony of ambitious choices gone awry.

Randolph and Zeta-Jones fare a bit better, while Ortega is mostly stuck in the eddy of repetitive behavior written for her thin character. The idea of this team of actors getting together for a scam is a fun one, but The Gallerist largely puts it to waste. It eventually grows kind of depressing, watching these talented folks (three of them Oscar winners!) unsuccessfully try to get a fire going.

The Gallerist is not without its occasional charms. There’s a chuckle to be had here and there, bits of zinging dialogue that actually find the right notes. Enough so that one roots for the movie despite its many missteps. The problem, ultimately, is that Yan chose a poor subject for her film, an environment that is an incredibly hard target to nail. A line of attack on such a frivolous and galling business must be done with laser precision, otherwise any attempt to skewer it is a dart into Jello.

It’s ironic that the film also features Charli xcx (who now lives in the Eccles theater, I think). Her own attempt at art vs. commerce satire premiered at Sundance the night previous, and it too has trouble landing its punches. In Charli’s film, they kind of just give up on the jokes and get serious pretty quickly. The Gallerist, though, keeps plugging long after it’s clear the gag isn’t working.

It does eventually get to a more somber tone, though, closing on a montage of characters as they presumably process all that’s happened. Only, look at how opaque and unreadable their expressions are. As if they, too, have no idea what it is they’ve just done, or what it’s all meant. Turns out, they didn’t understand the show either.