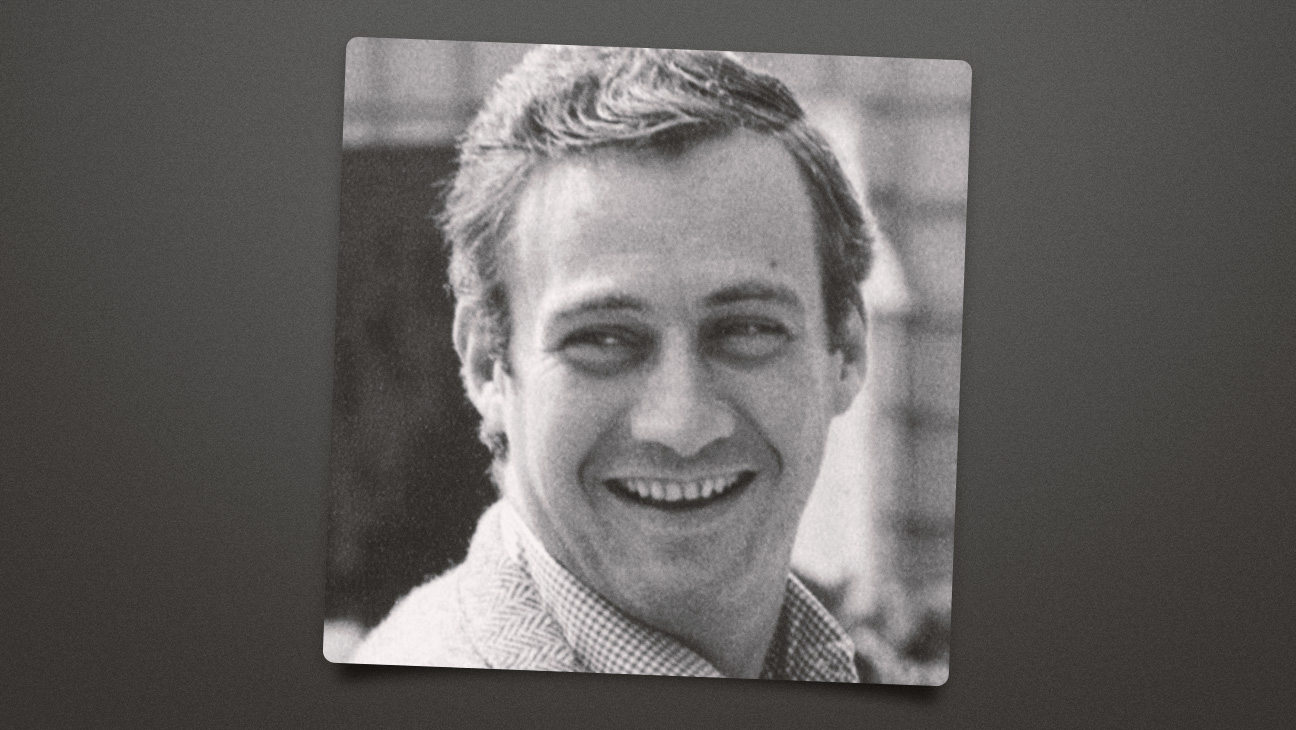

In 1972, at Duke Ellington’s spacious Harlem townhouse, director William Greaves captured living history on 16mm film. For four hours, figures from the Harlem Renaissance gathered in a spirited recollection of the first time Black American culture had the space to truly flourish as a free people.

The guest list included composer and pianist Eubie Blake and bandleader and lyricist Noble Sissle, both most known for one of the earliest all-Black Broadway shows, Shuffle Along. There’s photographer James Van Der Zee, who captured portraits of two important figures who both passed away in the 1940s, political activist Marcus Garvey and poet Countee Cullen — as well as the latter’s widow, Ida Mae Cullen, making sure her husband’s literary legacy was represented. There’s Aaron Douglas, whose paintings were his own form of activism, reflecting the racial struggles of the time.

Once Upon a Time in Harlem

A triumph of DIY filmmaking and an act of cinematic resistance.

The Great Migration gave Black Americans a chance to start over without being brutalized for the pursuit of knowledge, liberation and self-expression, and the amount of talent and history in the room is staggering. This film serves as a comprehensive introduction to the Harlem Renaissance, and as you watch, there’s an overwhelming urge to write down every name you hear and spend hours looking them up later.

Once Upon a Time in Harlem, recently debuted at Sundance, is a triumph of DIY filmmaking. Greaves had assembled a small team of four cameramen — including his son, David Greaves — and two sound engineers. Now, David Greaves completes his late father’s work, lovingly assembling the footage into a warm narrative that flows naturally from moment to moment. The conversation is lively, with people often chatting over each other and going on tangents. Split screen is used to show facial reactions while people are talking. The partygoers constantly encourage each other to speak, never wanting to hold the spotlight for too long.

At 100 minutes, Once Upon a Time in Harlem gives us only a taste of those magical four hours. But Greaves puts us right in the room with his naturalistic, vérité approach, making us quiet spectators among some of the most influential Black writers, thinkers, artists and entertainers to ever live. Elegantly dressed in long, flowing dresses and dignified blazers and looking right at home surrounded by shelves of books, these luminaries reminisce about a time when everything felt possible. With nowhere to go but up, writers and artists were engaged in collective, spontaneous creation.

The movie pays special attention to the figures that could not be present: Langston Hughes, Zora Neale Hurston and the aforementioned Cullen and Garvey. Garvey is both revered and mocked in the room, with each partygoer saying their peace; many remark on how he never actually made it to Africa, despite encouraging his fellow Black Americans to leave this oppressive country and return home. Hurston actually did make it to Africa and was one of the few Black women of her time to do so. Her fieldwork footage is among the earliest known filmmaking done by a Black American woman. Also prominently featured is the Langston Hughes poem “The Negro Speaks of Rivers”.

In one spirited exchange, the partygoers debate the use of the word “negro” as opposed to “Black” or “African-American,” and it’s fascinating to see how conversations that are now relegated to online discourse were happening in person among Black artists and intellectuals during the Renaissance, its aftermath and the birth of Black Power in the ’70s.

At a point when our culture is more fractured than ever by technology and social media, it’s inspiring to be reminded of the power of community as a mechanism for Black creativity. One element of the film that stands out is the focus on libraries as a safe home for writing, gathering, researching and record-keeping for Black writers and artists. Two librarians speak of their time at the 135th Street Library in Harlem, with an inspiring reverence for the space and their position within it.

Attempting to describe Once Upon a Time in Harlem with words feels inadequate. I watched it sitting up straight like a student in class, trying to soak up as much knowledge and history as I could. The moment it ended, I wanted to watch it again at home, pausing every few minutes to take more detailed notes of names and faces or add sketches of the various artwork presented. I approached writing this review with a great deal of anxiety, as the documentary reminded me of all the books I haven’t read and names I didn’t know.

But the beauty of the film is that it doesn’t judge viewers for what they do and don’t know, but rather encourages us to open our minds to history and see the connections between then and now. William Greaves was born in Harlem during the Renaissance, too young to be a part of it, but just old enough to understand the role of younger generations in keeping Black history alive. In a time when Black Americans have to deal with a government that wants to erase our history and minimize our accomplishments, Once Upon a Time in Harlem stands as a piece of cinematic resistance.