There’s a huge difference between memorializing a piece of pop culture and reanimating it. Dutch DJ-producer-musician Tom Holkenborg, who records as Junkie XL, achieved the latter in 2002, taking the semi-obscure 1968 Elvis Presley song “A Little Less Conversation” and remixing it for a Nike commercial. By adding an unrelenting backbeat, punching up the guitars and horns and funkifying the drums, the electronic overhaul transformed a throwaway tune recorded for a minor Presley movie into a 21st century global smash, catching fire in dance clubs and reaching No. 1 in over 20 countries. The track now lives on as a classic banger.

Four years after his glittering bio-drama, Elvis, Baz Luhrmann pulls off something akin to Holkenborg’s magic act with EPiC: Elvis Presley in Concert. The Australian director doubles down on his worship of a subject whose flamboyant showmanship, soaring emotions, perpetual motion and ravenous taste for bling make them very much kindred spirits. It’s as if Luhrmann were conducting a séance, awakening Elvis from the afterlife with a raw vitality and outsize energy that are rare even among the living.

EPiC: Elvis Presley in Concert

The King is reborn.

Calling the movie an archival doc or concert film might be accurate but somehow seems almost reductive. Much more than that, it’s a transcendent theatrical experience, an exhilarating party, a giddying visual and sonic blitz that will be an elixir to the Elvis faithful and an unparalleled primer for those who have never quite grasped what all the hysteria was about. The acronym that serves as the title is not at all hyperbolic. See the film on the biggest screen with the loudest multidimensional sound system possible and believe.

While he was making Elvis, Luhrmann began chasing after rumored footage shot for the 1970s concert films Elvis: That’s the Way It Is and Elvis on Tour but never used. In what sounds almost like an archeological dig, researchers found that material — 69 boxes of film negative totaling 59 hours — in Warner Bros. film vaults buried in underground salt mines in central Kansas. Additional Super 8 footage was discovered in the Graceland Archives, previously seen only in poor-quality bootlegs, plus a forgotten recording of Presley talking expansively about his life and career.

That latter find along with known recordings allows Luhrmann to construct his film as a first-person account; Elvis walks us through various aspects of his personal history and stardom, with candor, humor and even welcome humility.

Some detractors accused Luhrmann of beatifying his subject in Elvis — failing to take the superstar to task for his public neutrality on civil rights issues despite his freely acknowledged debt to the influence on his sound of Black music, particularly gospel and R&B. Those critics are unlikely to come away from EPiC feeling differently, though Luhrmann’s choice of images and calculated edits points up the very controlling hand of “Colonel” Tom Parker over the persona Elvis presented to the world.

In Luhrmann’s defense, he’s neither the first nor the last director to present immortal celebrity giants like Elvis, Marilyn Monroe, James Dean or Judy Garland as prisoners, or even victims, of their fame. Besides, this film makes no claims to do anything other than celebrate a legendary entertainer in full command of his powers.

While his Vegas residency at the International Hotel from 1969 to 1976 might be considered past that point, any effects of prescription drug abuse, weight gain and medical crises are negligible in footage that intercuts between those template-setting shows, tour dates and the rehearsal studio, often within the same song.

Working with Peter Jackson’s sound and picture restoration facilities in New Zealand, Luhrmann is able to present performances with crisp definition, lush colors and crystalline sound that give EPiC the same kind of thrilling, you-are-there immersive quality as great concert films like Jonathan Demme’s Stop Making Sense or Spike Lee’s American Utopia.

Nodding to the pearl-clutching caused by his stage gyrations, Presley skirts the issue of sexual suggestiveness. “Some people wonder why I can’t stand still while I’m singing,” he says. “I’ve tried it and I can’t do it.” Luhrmann is no stranger to continuous motion; his kaleidoscopic montages seem to spring from the same music-driven impulses as Presley’s dance moves.

Quick recaps cover the conservative backlash calling rock ‘n’ roll a cause of teenage delinquency; Elvis’ rise as a teen idol in formulaic bubblegum movies that molded his dreamboat image, whether as a cowboy, a race car driver or a beachnik; the media frenzy when he was drafted in 1958, eventually assigned to a U.S. Army division in West Germany; and his return to Hollywood, where attempts to rebrand himself as a serious actor floundered.

As soon as his movie contracts were done, Elvis threw himself back into live performances, eager to reconnect with his audience. Luhrmann and editor Jonathan Redmond thread biographical material throughout in the subject’s own words — no talking heads here — but the dominant focus becomes the shows. The director pulls back on his propensity to cut everything like a movie trailer and allows key numbers to play out at length. Presley comes across as the most generous of performers, holding nothing back in primal-energy concerts that leave him drenched in sweat.

Footage of the Vegas residency is especially vibrant in showing the bond between the idol and his fans, whether he’s beguiling them with velvet-vibrato seduction, pulsing like a turbo generator, striking karate poses or ascending to a massive finish on powerful gospel anthems like “How Great Thou Art.” His roof-raising take on Simon & Garfunkel’s “Bridge Over Troubled Water” will leave you breathless.

The shrieking young women are hilarious, as are their hairdos. One very funny snippet has Elvis giving a sweet peck on the cheek to a little girl at the lip of the stage followed by what appears to be her big sister latching her lips onto him like a mollusk before being peeled off by her mother. One woman holds up a sign reading “Kiss Me I Quiver,” which probably sounded less risqué in those more innocent times than it would today.

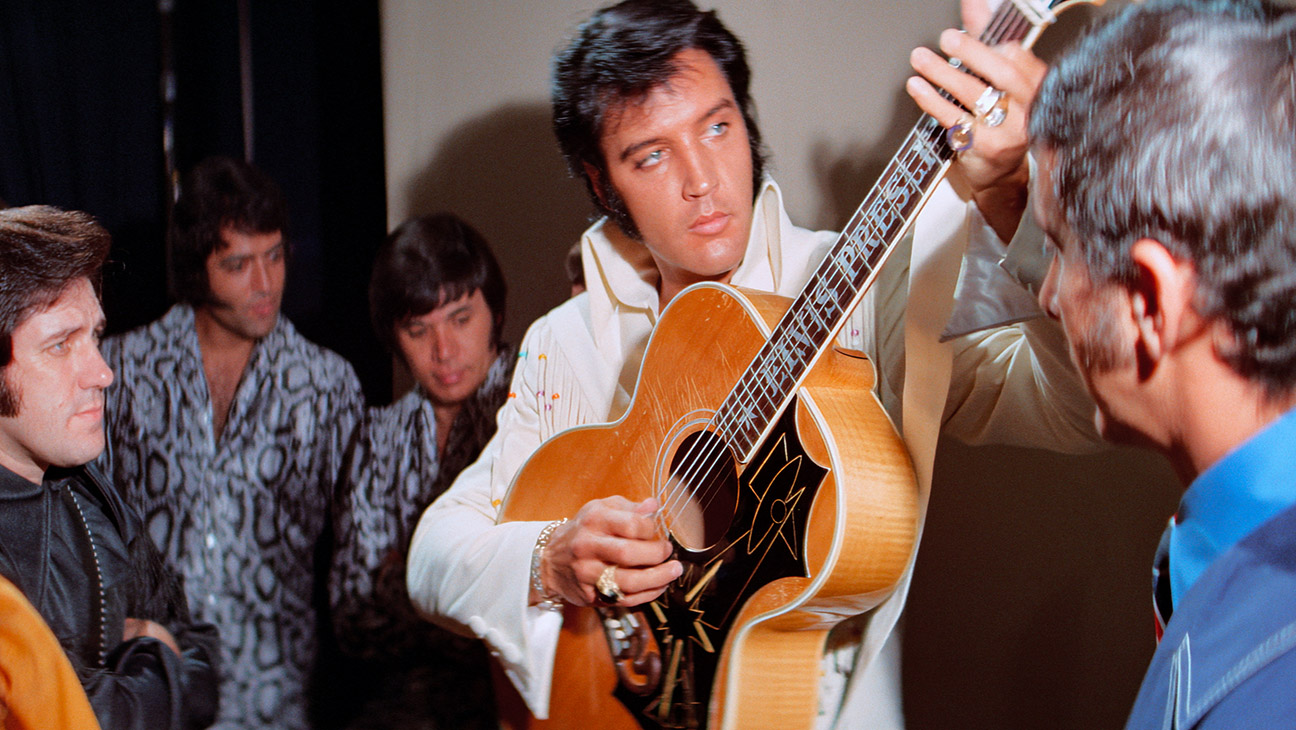

Watching Elvis interact with his musicians or flirt with his backup singers helps consolidate the impression that everyone on stage is having a blast. What’s remarkable is how spontaneous the shows feel, never slick or over-rehearsed, as if the guy in charge is intentionally keeping it loose.

The doc benefits from mostly going light on over-exposed monster hits like “All Shook Up,” “Hound Dog,” “Jailhouse Rock” or “Heartbreak Hotel,” instead favoring live staples like the rousing “Poke Salad Annie,” “Little Sister” with detours into “Get Back,” or “Never Been to Spain.”

That said, canonical tunes like “Suspicious Minds” and “Burning Love” up the excitement, while love songs “Are You Lonesome Tonight” and “I Can’t Stop Loving You” shift into more intimate mode. “Always On My Mind” adds some depth of feeling to an otherwise perfunctory acknowledgment of his wife, Priscilla Presley, whose story of trying to retain a sense of herself while being suffocated by her husband’s aura of adulation was told so tenderly in Sofia Coppola’s bio-drama.

In addition to the electric stage sequences, I particularly enjoyed glimpses into the rehearsal studio where much of the material for the Vegas act takes shape. In his super-cool chrome aviator sunglasses and a truly amazing iridescent psychedelic print shirt, Elvis gives the air of just hanging with friends as he dips into Beatles covers like “Yesterday” and “Something.”

The fashions in general are spectacular, none more so than the wild, custom-designed jumpsuits that were his Vegas signature — with lace-up chest closures, Napoleonic collars, half-capes, bell-bottom pants and whopping great belts befitting a wrestling champion, all of it embellished with gems, rhinestones, rivets and fringes.

One of the most remarkable things about EPiC, however, is that despite the outlandishness of the costumes, the movie never feels kitsch or frozen in time. It’s a pulse-pounding, foot-tapping, body-quaking record of a consummate performer, and Luhrmann reaffirms his love by making it too ecstatically alive ever to feel like a museum piece. To quote Ed Sullivan, who famously told his cameramen to shoot Elvis only from the waist up for the sake of family-audience wholesomeness, it’s “a really big show.”