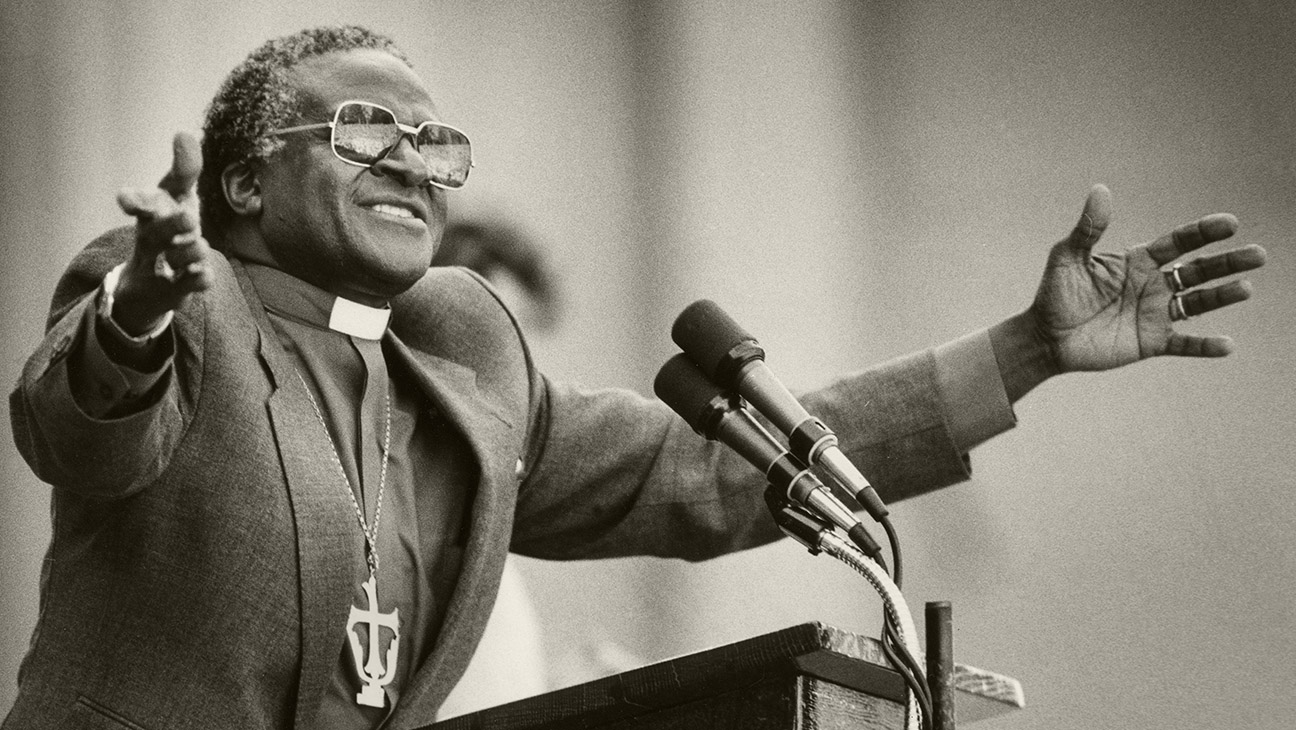

Cinematic biographies, like their printed counterparts, can be heavy lifting. We’re often barraged with a series of facts, dates and notable events, and the results can be dry as dust. That’s definitely not the case with Sam Pollard’s film about Desmond Tutu, whose importance to the ending of apartheid in South African cannot be overstated. But Tutu, receiving its world premiere at the Berlin Film Festival, offers more than an account of his historical significance. It presents a deeply personal portrait of the man, so much so that by the film’s conclusion you will feel as if you’ve truly come to know him.

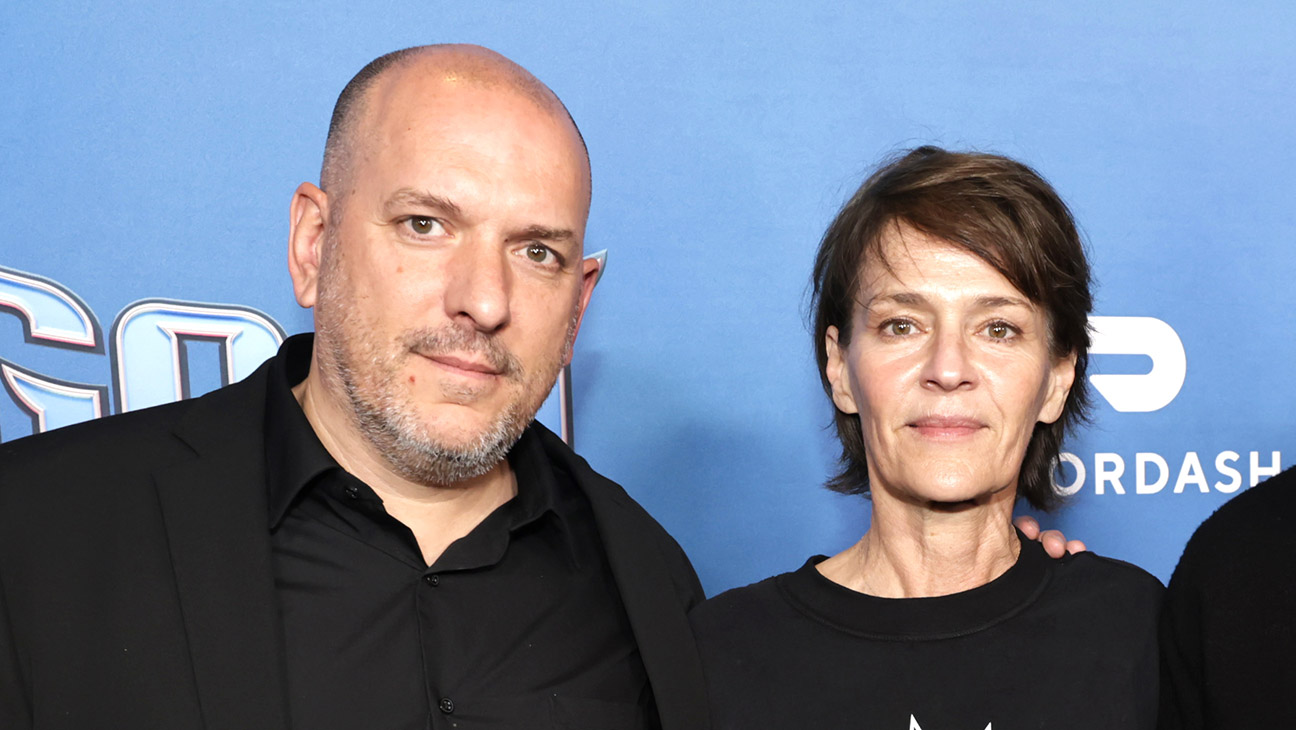

Pollard, whose directorial credits include such incisive documentaries as Citizen Ashe and MLK/FBI, had more than a little help in this regard. It came from Roger Friedman and Benny Gool, credited as “Consulting Producers” — the two journalists, one Jewish and one Muslim, filmed Tutu for the last 20 years of his life. Granted near-total access, they provided intimate footage of Tutu along with his wife Leah, friends and family members. We see him celebrating his birthday at a party in his backyard, his infectiously joyous laughter providing relief from the often difficult-to-watch episodes dominating the documentary.

Tutu

An invaluable cinematic portrait.

Tutu does dutifully chronicle the significant events in Tutu’s life, including the years he spent in the mid-1960s studying theology in London, where the contrast with how he was treated in his native country was transformative. Much to his wife’s dismay, they returned to South Africa, where he served in various teaching and theological positions. He eventually emerged as a leading figure in the anti-apartheid movement, along with Steve Biko, who was beaten to death while in police custody, and Nelson Mandela, who was imprisoned from 1962 until 1990.

The film — whose executive producers include Trevor Noah and Richard Branson — makes clear the personal danger that Tutu risked for his cause. “The hatred was so tangible among white people,” someone comments. “The miracle is that he came out of it alive.” Ironically, he later became an object of hatred for some Black people as well due to his steadfast rejection of violence to achieve political ends. We hear how he personally intervened, at great risk to himself, as a mob was preparing to murder an informer via the “necklace method,” which involved forcing a rubber tire drenched with gasoline around a victim and then setting it on fire.

One of the documentary’s most powerful segments involves Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher’s rejection of economic sanctions on South Africa. Tutu met with Reagan personally, but was unable to convince him to change his mind. The anger Tutu expressed was hardly of the priestly variety: “The West, as represented by President Reagan, can go to hell as far as I’m concerned!” he thundered.

Tutu’s selection by Mandela to head the Truth and Reconciliation Commission provides another memorable moment. We see him breaking down in tears while listening to a survivor’s testimony about the torture he suffered at the hands of the government.

To escape the pressures of his work, Tutu spent time at retreats in Sweden, where he reveled in the solace and quiet. He traveled to another Scandinavian country, Norway, to receive the Nobel Peace Prize. (He actually won the prestigious award, as opposed to strong-arming another recipient to hand theirs over.)

But where the film excels is not so much in the biographical details and archival footage, as compelling as they are, but rather in the humanistic portrait of the man whose warmth and outgoing nature are vividly shown. Besides the many interviews with him and his wife, we hear from such confidantes as his press secretary, personal assistant, aides, fellow church leaders, friends and family members. It seems more than fitting that the last words we hear in the film are “God bless you,” uttered by Tutu himself.