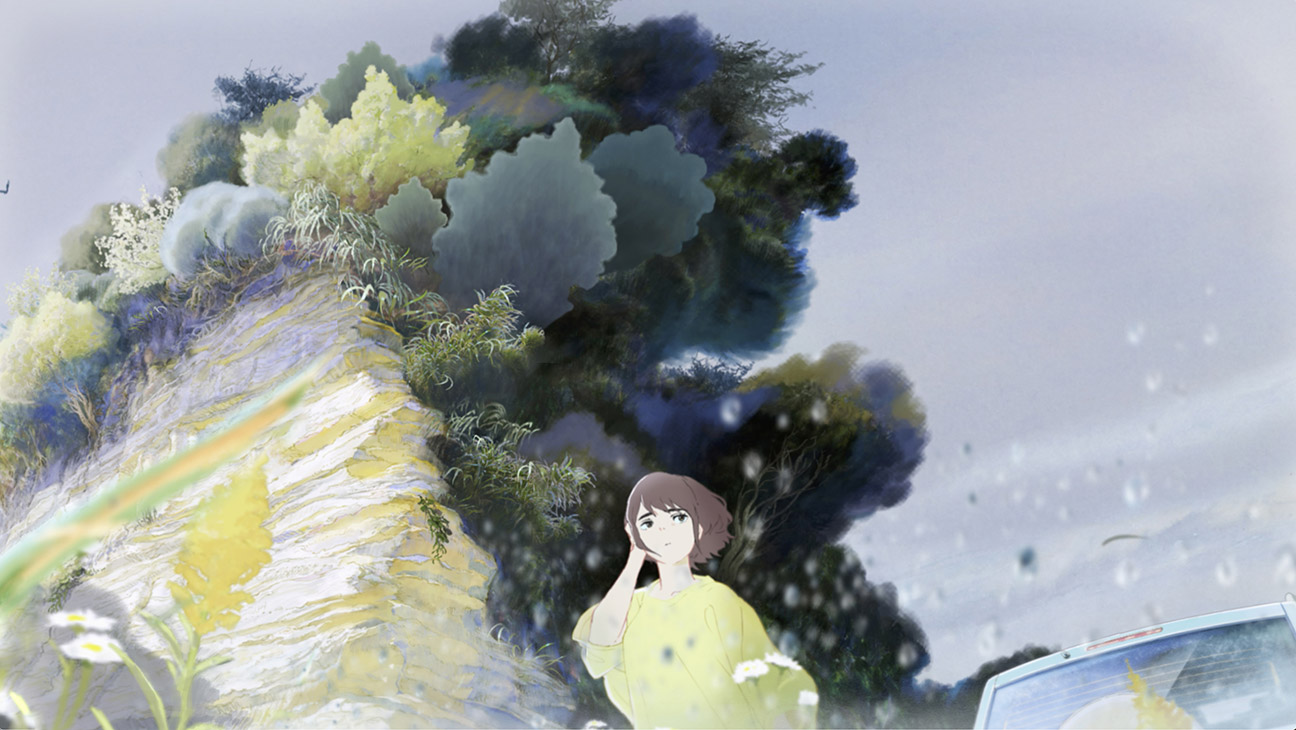

Beautiful if somewhat baffling Japanese animated feature A New Dawn may just possibly do for fireworks and administrative subrogation (a phrase mentioned throughout) what Akira did for mutant teenagers and post-apocalyptic dystopias, or what Spirited Away achieved for Shinto deities and abandoned amusement parks.

The brainchild of visual-artist-turned-writer-director-animator Yoshitoshi Shinomiya (who oversaw the distinctive watery flashback sequence in animé hit Your Name), this offers a heady blend of painterly backgrounds, traditional character animation and even a kicky blast of claymation. It’s all there to serve an odd central story about three friends since childhood banding together when a beloved home/fireworks factory in their provincial hometown is about to be seized and destroyed by the municipality to recover unpaid debts and then redevelop the land. (The last bit is where the administrative subrogation comes in.)

A New Dawn

Don’t think too hard about it.

Bowing in competition at the Berlinale, a festival that’s put Japanese animation on the same footing as live action cinema ever since Spirited Away won the Golden Bear in 2002 (ex-aequo with Bloody Sunday), this looks destined to travel. But while Shinomiya’s visuals are admirably original, the script doesn’t have the emotional heft that helps the best Japanese cartoons (like Your Name, Spirited Away or really almost everything by Studio Ghibli) crossover beyond niche fan bases. Still, it drifts along pleasantly enough, given an extra push by Shuta Hasunuma’s EDM-inflected soundtrack and trippy visuals that would suit being consumed with a side of edibles.

Although there are flashbacks throughout that add texture or reveal plot points, the story is pretty straightforward and told roughly chronologically. In the opening scenes, we meet the core trio as teenagers growing up in a small seaside town. Serious, bespectacled Sentaro Obinata, aka Chichi (voiced by Miyu Irino), and his wilder-spirited kid brother Keitaro (Riku Hagiwara) live with their father Eitaro (Takashi Okabe), a widower, who’s taken over the family business creating handmade fireworks. This is a skill that Eitaro’s late wife’s family pursued for many generations, stretching back to their days as pirates. The sons’ best friend is Kaoru Shikimori (Kotone Furukawa), a girl from a more conventional family, who longs to get into the firework business.

However, on the day we first meet them all, town officials (a party that includes Kaoru’s own parents) have arrived to serve Eitaro papers that will compel him to sell the factory/house to meet his debts. The kids are distressed because they love the multi-story, ramshackle building that has a view of a sea inlet and is backed by a forest full of ruined shrines and caves full of local history.

Four years later, the house is only just still standing. Eitaro has gone and Keitaro is living in the house by himself. Chichi, who has gone to university and since gotten himself a job working for the very municipality that persecuted his father, shows up in Tokyo to convince Kaoru — now a university student who has built herself a reputation putting on light projection shows — that she must come home to help him get Keitaro out of the house before the authorities remove him.

There is a lot of talk about why the local government wants to buy and destroy the house, none of it very easy to follow, but it sounds like a case of eminent domain that’s gone very much against the Obinata family’s favor. In any event, they’ve already drained the sea inlet and filled in the hole with solar panels, which may be eco-friendly but are less picturesque than the water that used to be there.

Judging by the flashbacks here (and in Your Name for that matter), Shinomiya clearly loves illustrating watery realms with their shimmering surfaces and liquid movements, which rhyme and resonate with the near-abstract patterns fireworks make in the sky, all of which come together in the climactic sequence. It turns out Keitaro wants to go out with a literal bang when the sheriffs arrive to drag him away, setting off a daddy-of-all-fireworks device called the shuhari, which will unleash a fiery spectacle that has all kinds of spiritual meaning for the Obinata family and significance from the lore around fireworks.

Although viewers unfamiliar with that lore and its importance in Japanese culture may feel a bit bemused by all the yammering about it here, it’s worth it for the lush climax, executed with a range of animation techniques (both traditional and CGI-based) that make it all feel truly hallucinatory. Best not to think about any of it too much and just stand back and go “ah!”