The cast and creative team behind Amazon MGM Studios’ upcoming film Mercy took to the stage Thursday for a panel at New York Comic Con to discuss their unique approach to filming the upcoming title and to reveal the film’s trailer.

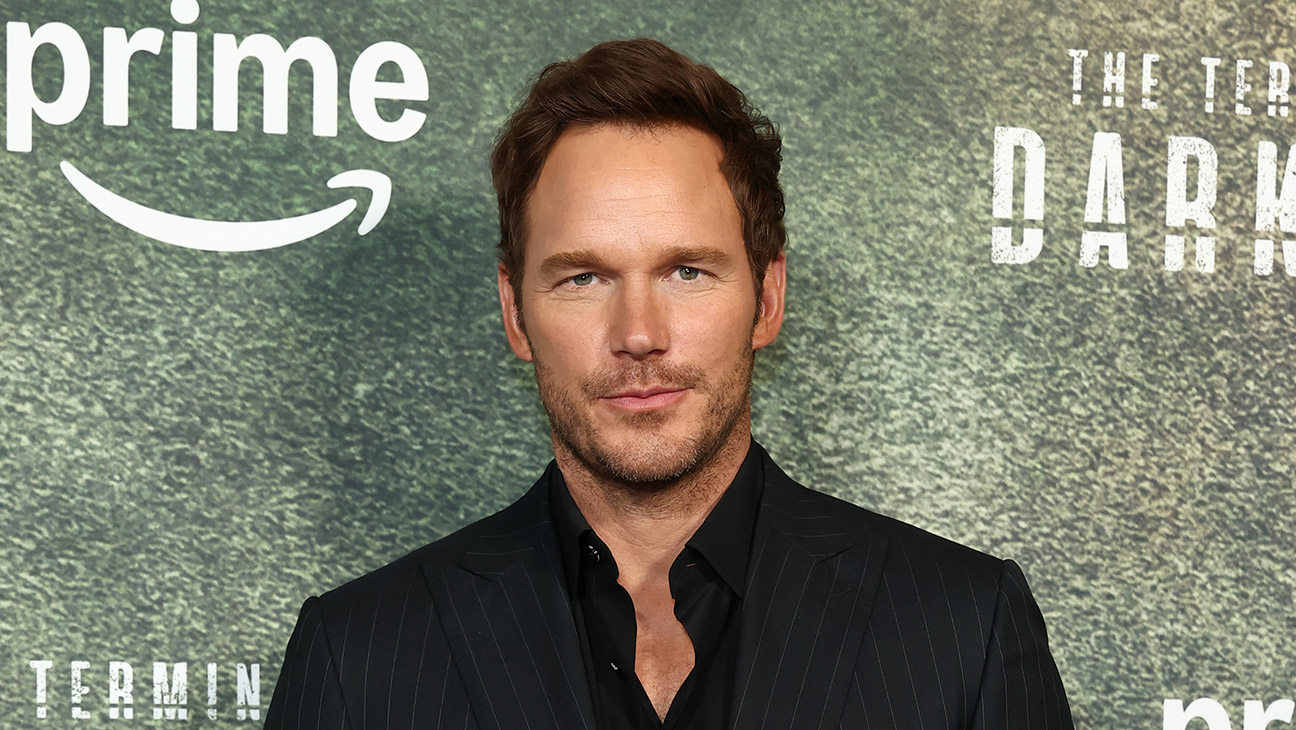

Pratt, his co-star Kali Reis, director-producer Timur Bekmambetov, and producer Charles Roven were present at the panel hosted in New York’s Jacob K. Javits Convention Center about the upcoming film, which bows Jan. 23, 2026. Set in 2029, it follows Pratt’s LAPD detective who wakes up strapped to an execution chair. He’s on trial for murdering his wife and has just 90 minutes to prove he is innocent to an advanced A.I. system known as Judge Maddox (Rebecca Ferguson), which is acting as his literal judge jury, and executioner.

The panel kicked off with a video message from Ferguson, who apologized for not being in attendance, and then teased some “mind-blowing footage,” which Pratt soon appeared to reveal included a first look at the film’s nearly three-minute trailer.

“This was a departure for me,” Pratt noted. “He is a homicide detective in the near future, and a guy who has seen a lot, been through a lot. He’s part of this special new Mercy program that they’ve designed, essentially using AI to modify their core system to be more efficient, and to face the rise in capital crime in this version of Los Angeles. They just want to get these murderers off the street and send a message.”

“There is something new for Chris in this movie. It’s his next iteration. He plays a dark and very vulnerable character in a very dramatic story,” said Bekmambetov, while discussing the casting of the film. As for the rest of the casting, Bekmambetov noted he chose them “because they are very different” performers. “[Chris is] famous for his action movies, but playing a dramatic role, and he’s literally electric chair for 90 minutes. Kali is playing his partner, helping him, we think. And Rebecca is an AI judge. She’s smart, and we will discover her heart.”

Reis, speaking to her character, shared that “she’s very loyal, but she does also have some things about her that you have to discover, I had to discover reading the script,” Reis said. “The script provided such a baseline for me to really dive deep, to build her backstory, because there’s a reason why she believes in this court so very much.”

While discussing how the film’s runtime influence on the storytelling, the director noted Mercy’s 90 minutes are “a great tool, because we were limited. We had a rule that we needed to tell the story in real time. It’s 90 minutes of this ticking clock in this courtroom. It’s a practicality, but also we live in the world today where I think AI is coming. It’s knocking on the door, and we don’t have time to understand what will happen, how we will live in the world, if AI will be our friend or AI will be our enemy, or AI will be our child. But we need to teach it how to behave.”

For producer Roven, the AI element was part of why he signed on. “Back when we first got the pitch, people were talking about AI, but it wasn’t really happening yet. Then by the time we got the script and we started talking about the movie, now all of a sudden, companies were really dealing with AI, and the future was definitely not so far away,” he said. “I think the fact that the movie takes place in 2029 — every day, every week, every month that goes by, there’s something more that makes our movie true.”

“The thing that you’re going to walk out talking about is, is this going to happen?” he added later in the panel. “There’s a lot of things that speak to if we should try it, because of what it would do to time and space in terms of having somebody that’s an AI — even calling it somebody, it’s really not — this piece of equipment that actually can, in an instant, amalgamate all of this evidence and come up with this person is most probably innocent, or most probably this person is guilty. Is that good? Is that bad?”

Much of the rest of the panel focused on the movie’s distinct visuals and filming process for a story that explores, in part, how screen life overlaps with physical life. “We live half of our time in the physical world right now,” said the film’s director. “Half of my time I am spending in a digital world. It means half of the most important events of my life are happening, not in the physical world.”

In the film, that translates to “sometimes up to 1,000 screens in front of me of this character’s digital life over the past 10 years being used as evidence against [him],” said Pratt. “We had to shoot me in the chair, but we had to shoot every bit of that stuff that would then be put in post production and provided: me yelling at my wife on my daughter’s Instagram, her secret Instagram page that I find out she had or various FaceTime calls that were stored in the cloud that is used as evidence against me. All my friends, all my family, the things that they’ve said, security footage,” he explained.

Beyond what his character sees on those screens, Pratt’s cop interacts not just with Ferguson’s AI, but his character’s policing partner, an experience Pratt called “a very high production value Zoom session of two people on two different sets,” with Reis “essentially this projection hologram” with the actress being filmed on a separate set “and her image was projected for me to see, so I was acting opposite her.”

“A lot of what you see is her point of view on me. We did takes that were sometimes 50, 60, and 70 minutes long, so we shot the entire thing almost as a stage play all the way to the third act,” he added. “We just blazed through the whole thing, which was an incredible challenge, and something that was different than anything I’d ever done before.”

Later in the panel, the director and producers went deeper into how they combined practical and green screen effects, along with the movie’s IMAX experience, and how the director’s own interest in people’s screen life influenced the film and shooting.

“We really shot in downtown. There were like five, six shooting days in the mornings because we were trying to keep it magic hours,” Bekmambetov explained. “And then we had unique technology to combine what we shot with the footage from virtual production. All that we shot downtown was projected, and there was a track on stage where some action happened… Then we had a session in visual production, and, of course, visual effects helped us a little bit.”

“It was the first time we did as much footage on what we call a volume stage, which was taking stuff that we would shoot and putting it on screens,” said Roven. “We were not only in the second unit using vehicles, but we would bring those vehicles onto the volume stage and put them on rollers. There’s a scene in the movie where… [a] truck hits a cop car and the cop car goes careening into a building where people are having dinner, and it takes a number of them out. We shot that for real on the volume stage, with the truck, with the cop car going into the building. Normally, it was in the area where the crew would be watching the shot, so we had to be very careful because we almost took out the crew.”

He continued, “The whole scene took like three minutes to shoot, and that’s the other thing that you find making a movie on a volume stage. Even though you go out and you shoot pieces of it elsewhere, on that stage, things happen very quickly.”

Bekmambetov also noted that they used robodogs to help film at least one sequence. “We used robodogs, for maybe the first time in the history of filmmaking,” the director said. “Cameramen were robodogs because I used the footage of the robodogs going through the extras in a crowd through the scene and filming it. How I directed the robodogs was that I just told them what I wanted. I said, ‘Go over there and film these guys,’ and it happened.”

As for how audiences will experience this film, the panelists stressed seeing Mercy in IMAX. “The experience will give you a real-life sense of what Chris is experiencing in the chair. Because those screens will not just come at you in a 2D way. They’ll almost look like they’re coming at you out of the motion picture screen into the audience,” said Roven.