Most people claim to know what “American” means, but few probably know the meaning of “Pachuco,” nor the name of the playwright and director who helped introduce Pachucos into popular culture.

For those not in the know (and that includes this critic), David Alvarado’s American Pachuco: The Legend of Luis Valdez stands as a welcome corrective. More importantly, the well-informed film comes at a time when its very subject matter — the long, tough fight for equality and recognition waged by Latinos in the U.S. — is once again making headlines. Understanding the life and work of Luis Valdez is a way to broaden one’s understanding of what it means to be American, perhaps now more than ever. Watching this enlightening and entertaining documentary is a good way to start.

American Pachuco: The Legend of Luis Valdez

A generous homage to a major Latino talent.

First things first: Pachuco was a term used for Mexican American men in the 1930s and 40s who wore flashy zoot suits, spoke their own slang and formed a small but notable countercultural scene in Los Angeles. “Street cats with style,” is how Valdez describes them. They became popularized by the playwright in his hit 1979 production Zoot Suit, which was the first big acting break for Edward James Olmos. Historically speaking, the Pachucos marked a moment in U.S. history when Latinos were facing major discrimination as their communities grew and they strived to make themselves heard.

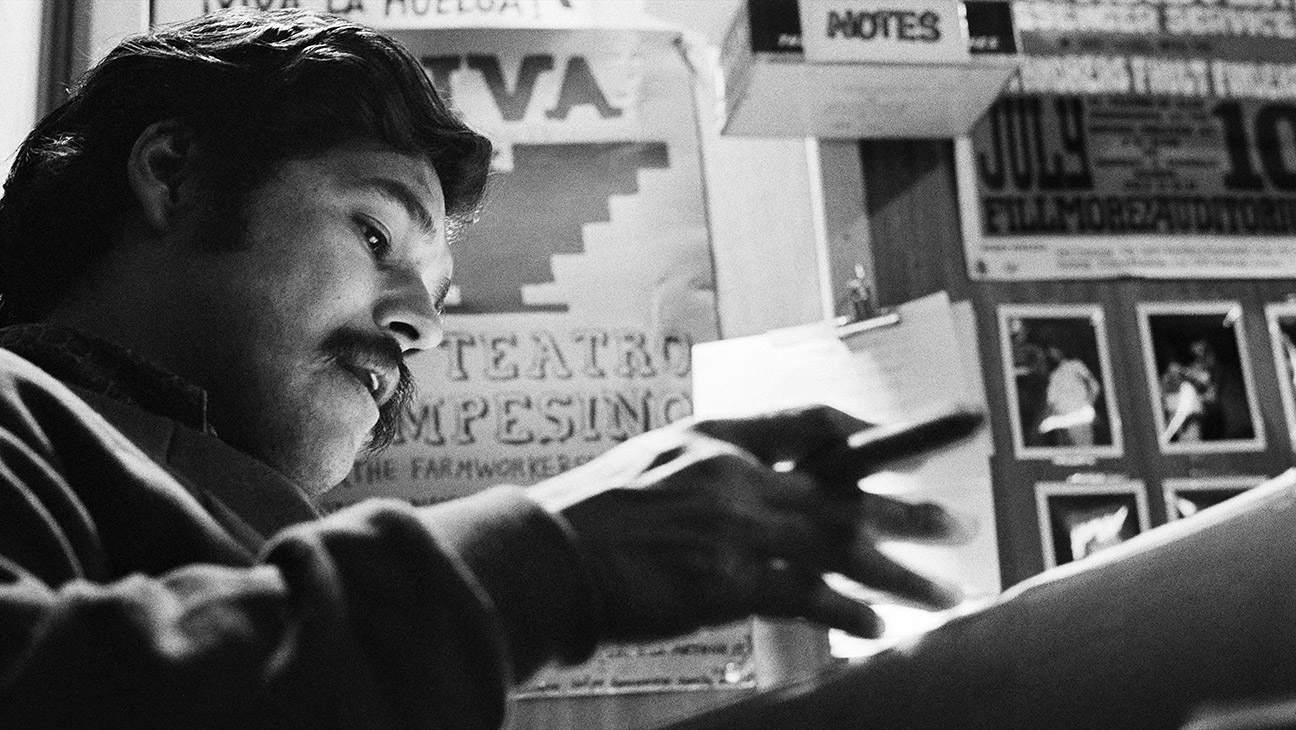

Valdez, who was born to Mexican immigrants in 1940, was too young to be a Pachuco himself, but his life was shaped by a similar need to channel his own distinct language and heritage. Raised by farmers whose work he describes as “literally slave labor,” he began writing and performing plays at a young age, focusing on the Chicano community he grew up in. When his hometown of Delano became the heart of organizer — and former Pachuco — César Chávez’s labor movement in the mid-1960s, Valdez created El Teatro Campesino (The Workers’ Theatre), producing energetic agit-prop satires that accompanied the farmers’ demands for better wages, health care and union protection.

Alvardo’s doc traces Valdez’s rise from poor farm boy to prolific and politicized playwright, and finally to hitmaker when Zoot Suit became a stage sensation in L.A. Loaded with archive footage and one-on-one interviews with the 85-year-old Valdez, as well as close family members and artistic collaborators, the doc is fairly conventional in form except for one twist: An unseen narrator (played by Olmos) tells Valdez’s story in the voice of a Pachuco, describing the playwright’s impressive run with plenty of swagger.

In 1969, Valdez moved his troupe to Del Rey and established a cultural center for Chicanos, attracting international talents like the British theater director Peter Brook. Hoping to “create something more substantial for the mainstream,” Valdez began working on a piece inspired by the 1943 Zoot Suit Riots, during which Pachucos were subject to racist attacks — including being stripped in public of their prized uniforms — at the hands of U.S. servicemen and other white residents of Los Angeles. Olmos, who was a local rock singer but had never really acted, was cast as the show’s lead, narrating the action in caló slang. “He gave me the voice that our people needed to hear,” he says of Valdez.

When Zoot Suit premiered in 1978, it became a “Chicano smash hit” that played to packed audiences in L.A. for nearly a year. The show was invited for a run at the Winter Garden Theatre on Broadway, with a sold-out premiere attended by the likes of Mick Jagger and Andy Warhol. Then the reviews came in: Zoot Suit was panned by New York critics, including one from the Times, who called it “overblown and undernourished.” Other reviews were tinged with racism. (“White Americans will be uneasy,” one critic wrote.)

The Broadway flop was a major blow for Valdez — “the critics wanted to strip me naked,” he gripes — though he did make a feature-length movie of Zoot Suit in 1981, starring the same cast as the stage version. It was the director’s first stab behind the camera. He followed it up with La Bamba, a low-budget biopic of Chicano rocker Ritchie Valens that became a box-office hit and remains the most successful Latino movie of all time.

The end of American Pachuco focuses on La Bamba’s development and production, including interviews with producer Taylor Hackford and star Lou Diamond Phillips. The latter was an unknown Filipino American actor whom Valdez chose to cast after auditioning over 600 talents, picking Phillips despite the fact that he wasn’t Latino. (“He was a product of racial fusion,” the director explains.) What made the film click both commercially and emotionally is the way Valdez sought the universal in the personal, fusing his own story — including his troubled ties with an older brother — with that of Valens, and other Chicanos, who overcame poverty and racism to make it in the U.S.

Considering the success of La Bamba (the film grossed $54 million off a $6.5 million budget), Valdez could surely have stuck around Hollywood to direct more movies. We never learn why he didn’t, though perhaps his political stances and cultural identity didn’t jibe well with the industry.

At the end of this informative and generous doc, we leave the octogenarian in front of his typewriter, still hacking out plays and scripts, giving life to a community whose slow but sure ascension represents the American dream in a nutshell.