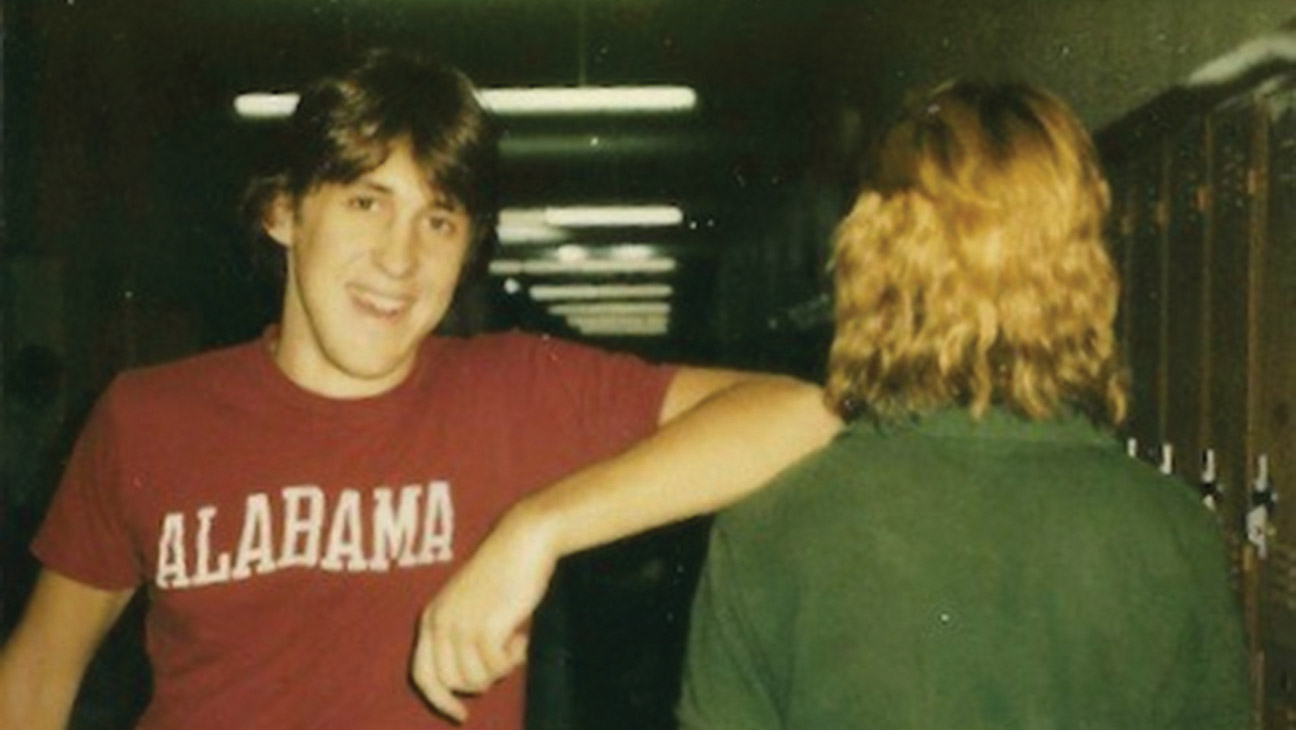

With his semi-autobiographical film Almost Famous, Oscar-winning writer-director Cameron Crowe tapped into his past as an outcast high schooler turned unlikely Rolling Stone reporter. With his memoir The Uncool, he is returning to that well, this time without the veneer of fiction, offering equal parts dishy and insightful stories of his time chronicling the kings and queens of ’70s rock, from David Bowie to Joni Mitchell.

Ahead of the book’s release (Oct. 28 via Simon & Schuster), Crowe spoke with THR about his memoir, an impending return to the director’s chair and his onetime plan to get Hollywood legend Billy Wilder to direct a Soundgarden music video.

How did this memoir come about?

I was working on a collection book of journalism because I never put one out. I started re-interviewing as many people as possible who were at seismic points in their lives when I first did the Rolling Stone stories. That unlocked all the stories behind the stories and got me thinking about the things that I had never really written about, including my family. I wanted to write it on yellow legal tablet sheets, like I used to write all of my earlier profiles, just for pure love of writing. At the same time, I just wanted to write something about these people who were either lost in the mists of time or maybe hadn’t made it.

Who was someone you wanted to revisit that fits that description?

Jim Croce. Not a lot is known about that guy, and I was with him for a day and a half, when all of his dreams were suddenly within grasp. His records were starting to be played. He was used to not having success. I was going to interview Looking Glass, and they stuck me in a back room at the concert because I was underage, and it turned out to be Jim Croce’s, the opening act’s, dressing room. He assumed I was there to interview him. He asked me to come by his hotel the next day, and I skipped school and did it. I just found it really poignant to write about this guy who was dead, like a year and a half later.

You have revisited this time in your life before, most notably with Almost Famous. What did you want to have in this book that you didn’t have in there?

I’ve got to say my family and my father. My father is not in Almost Famous, but he was very much a quiet hero to me. He was somebody who had left a celebrated military career to look after his family. I owe my life to that decision he made to downshift into a domestic life. I wanted to end the book with him staying up all night taping an Allman Brothers concert [on New Year’s Eve] for me.

The book is about your career in journalism, but you do go over your transition into filmmaking with Fast Times at Ridgemont High, which you wrote. When you entered Hollywood, did you think your time in journalism was done?

I’m still on the masthead of Rolling Stone, believe it or not. I still think of myself as a journalist, even as a director. When I was given my first chance to be around a movie based on something I’d written, it did seem like a dream that may or may not evaporate. But I think that was true of so many of the people that were working on Fast Times because there weren’t any movies about young people populated solely by young people. The studio thought it was a mistake when they saw it. Although, Sean Penn definitely had a sense of destiny. The guy had already unlocked his personal code for how to act and inhabit a character. Who would think that a guy that young would say, “I’m gonna go full Method. I’m going to make sure that nobody calls me by my name for two months straight.” That was crazy for a guy that had like one credit and nobody had even seen it yet.

What were some of the studio notes you were getting?

That there was going to be no audience because there wasn’t a nostalgia quotient that would make it relatable, like American Graffiti. The thinking was that if you have something that adults would appreciate, too, then you have a double bite at the apple. That’s why no movies about young people, from a young person’s point of view, really existed. They said, “Let’s go to the funeral” on the way to the last preview. But [director] Amy Heckerling knew what the goal was, and adults existed only as teachers in that movie. Of course, the studio was playing catch-up because they never were able to get the theaters back. [Universal gave Fast Times a limited theatrical release in 1984. Despite this, the film went on to earn more than four times its budget at the box office.] Movies about young people have always been important, particularly if they’re authentic and don’t sound like they’re 40-year-olds speaking teenage language. It was the right time to blaze a path, though we didn’t know it was a path that we were blazing.

Was there something you and the Fast Times team fought to keep in the movie?

The lack of a romantic vision of first-time sex. It was a lot more real, and it was a little bit hard to watch. She is in a dugout, and what is she looking at while she’s losing her virginity? Somebody’s graffiti that says “Surf Nazis must die.” That was on the level of emotional candor that I don’t think people were ready for, until young people saw it and said, “I get that.” If something comes out that hits the mark in the right way, it becomes a high-pitched signal. Everything in the world is marketed now, but sometimes stuff happens on its own gust of wind because it’s just something you need to share. That’s what the book is about — not to be a guy pitching a book — but it’s about the nobility of the fan experience.

You are set to direct a Joni Mitchell biopic next year. Your most recent movie, Aloha, was in 2015, and a lot has changed in Hollywood in the past decade. What excites you and concerns you about getting back into filmmaking?

I learned something writing about Billy Wilder, who was my hero, when I wrote the book Conversations With Wilder. I saw how a guy in his 80s and early 90s still remained curious. I tried to get him a job directing the Soundgarden video for “Black Hole Sun.” I just thought that would have been amazing.

That would have been incredible!

I know! Like, the last thing Billy Wilder directed was a Soundgarden video, that was my dream. The gift that he gave me is knowing that filmmaking is a lifetime craft, and hallelujah for that. I have put a lot in my creative back pocket, and I’m really excited to pull it out and put it on the table for the next movie I make.

This story appeared in the Oct. 22 issue of The Hollywood Reporter magazine. Click here to subscribe.