The Oscar-nominated film Hamnet was co-written, directed, co-edited and executive produced by Chloé Zhao, but it took a village — including five of the top producers in the business — to help the Chinese auteur bring to the screen her adaptation of Maggie O’Farrell’s acclaimed 2020 novel about the Shakespeare family and the tragedy that may have inspired Hamlet.

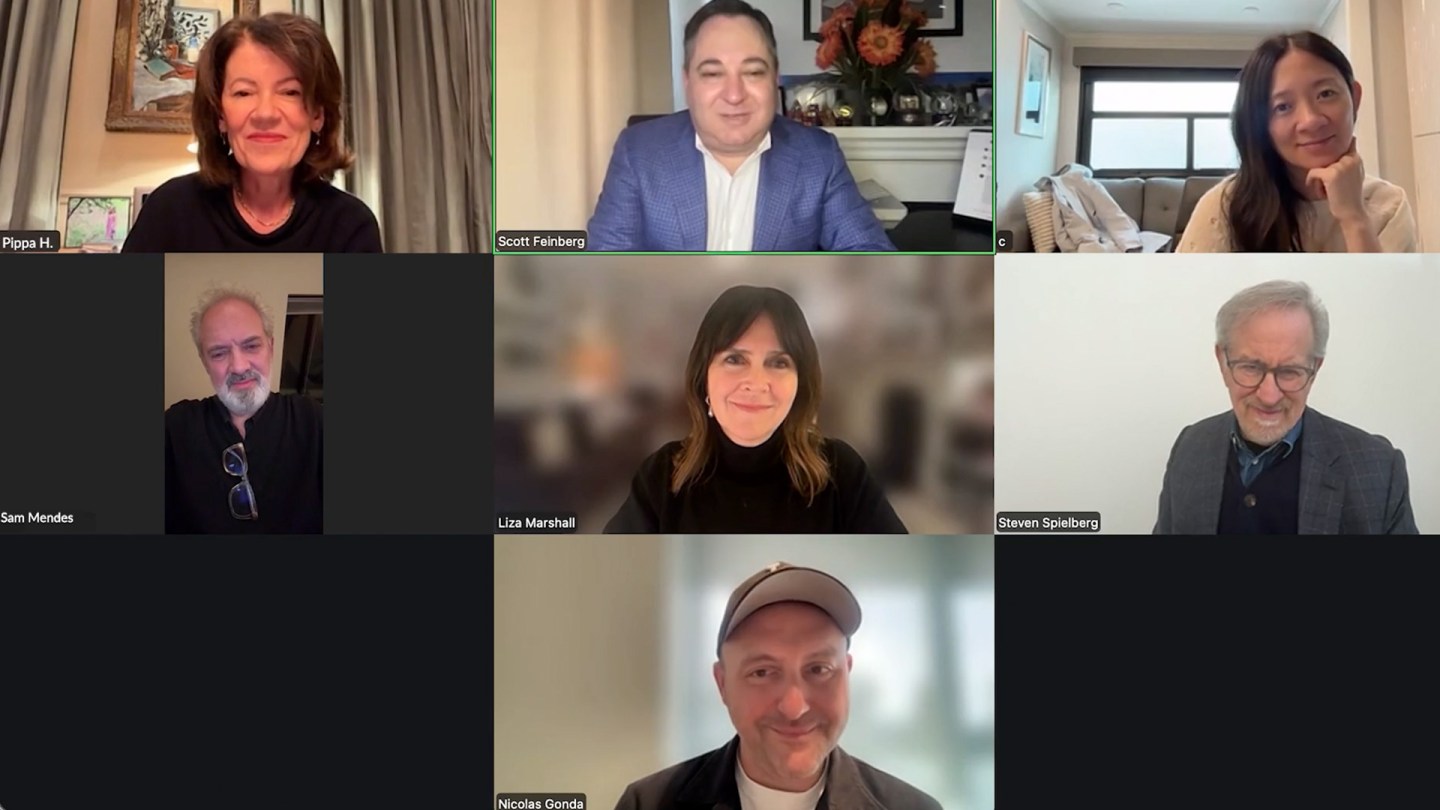

This week, as you can watch for yourself via the video below, The Hollywood Reporter exclusively spoke with Zhao, who is Oscar-nominated for best director and best adapted screenplay for Hamnet, and the producing quintet who share the film’s best picture nomination — Hera Pictures’ Liza Marshall, Neal Street Productions’ Pippa Harris and Sam Mendes, Amblin’s Steven Spielberg and Zhao’s partner at Book of Shadows, Nicolas Gonda — about their journey with the project.

Cracked Zhao at one point: “I just want to acknowledge these five producers for being the advocates for my madness!”

Marshall, a fan of O’Farrell’s prior books, was sent Hamnet in galley form by the author’s agent in 2019. “It just had such a profound effect on me,” she recalled, noting that she, like protagonist Agnes, is the mother of two boys. Marshall immediately felt that the book had cinematic possibilities, and after connecting with the agent and O’Farrell via Zoom, secured its rights.

Harris didn’t read the book until it was published, but once she did, and then learned that the rights had already been purchased, she reached out to Marshall, a former colleague and longtime friend, to ask if Marshall might want to team up with her and Mendes.

Marshall agreed, and Mendes contemplated putting forward himself as the director — but, despite his long association with Shakespeare-related works, Mendes ultimately decided he was not the right person for the job. “I felt like it needed someone who was going to make the familiar strange again,” he said. “It didn’t feel like me. But I felt it should be a movie, and I felt like it might be in Steven’s wheelhouse.”

Mendes reached out to Spielberg, whose studio DreamWorks had handled Mendes’ directorial debut, American Beauty, 27 years ago, and whose company Amblin had also backed Mendes’ film 1917 six years ago. On paper, Spielberg made sense for the job, having worked on prior films in a wide array of historical periods and with children.

But, Spielberg recalled, “When Sam sent me the book, I was very excited, I read it right away, and I called Sam back and said, ‘Can I have two weeks with this? Because it won’t be an easy yes and it won’t be an easy no.” He added, “I’m very realistic about subject matter that I am not as good for as other directors might be. And after wrestling this for about a week, I called Sam back and said, ‘I want to make this with you, but I’m not the right choice for this.’”

Spielberg suggested Zhao, whose earlier films — including Songs My Brothers Taught Me, The Rider and best picture Oscar winner Nomadland — had greatly impressed him. “Chloé has an uncanny rapport with mother nature and human nature, which is the essence of what Maggie O’Farrell wrote in her book. So Chloé came to mind instantaneously.”

For Zhao, though, it wasn’t an immediate yes. Since making Eternals for Marvel in 2021, she experienced a “mid-life crisis” and had not directed another film. And when Spielberg floated the idea of Hamnet, she had an “initial pause,” wondering, “Can I handle this?” Her prior films had either not included a mother character or had included a deeply flawed one, something that she attributed to her own “deep mother wound.”

What got her past the fear of “opening my own wound” and to agree to helm Hamnet? “A big part of it was to look at this team that you’re seeing on this Zoom call,” she emphasized. “They come from very different experiences… but they perfectly complement each other… and that started to give me more confidence.”

Gonda, who produced films for Terrence Malick before partnering with Zhao in 2023, echoed that sentiment: “The more that Chloé looked at Hamnet, it felt like this puzzle piece that we had been looking for.”

With Zhao on board, the producers prepped for a trip back to 17th century England. Harris, who has produced many period pieces, explained, “This is obviously a very difficult period, in terms of production, because so little exists still in the U.K., in terms of the buildings that Shakespeare would have seen. A lot of them got burnt down in the Great Fire of London. So this one presented particular challenges in terms of finding the architecture, but also because Chloé felt strongly — and rightly — that she wanted to film far away from London, that she wanted to find a forest which really felt like it was absolutely in the middle of nowhere.”

Once the locations were secured, Zhao and her team embarked on a 46-day shoot. Marshall was on set every day, but the other produced popped in and out, and Spielberg said that he had never seen anything like Zhao’s directing techniques, which included leading the cast and crew in guided meditations and literally crawling into the weeds to lay beside star Jessie Buckley ahead of a birthing scene.

“Chloé just wants everyone to be present, not just the people in front of the camera, but behind the scenes,” he explained. “She made everybody, including me, a producer and a visitor on her set, feel very safe, that there was nothing anyone could do on Hamnet that would fall into the category of having made a mistake. With Chloé, there are a lot of happy accidents, but there are no mistakes.” He added, “I had never quite seen anything like it before.”

Marshall concurred: “The set was unlike any I’ve ever been on. It was incredibly peaceful and nurturing. Even though it was incredibly sad at times, I think Chloé’s genius of doing dance takes at the end of every week with all the cast and crew just allowed everyone to shake off the heaviness of the emotion in such a brilliant way. Particularly for the children, what they could take away was the memory of dancing, not the memory of dealing with death.”

Contextualized Gonda, “Chloé always knew from the beginning that you can’t make a film about love in an environment that is harsh and transactional. The process had to reflect the story.”

Once the finished film began to be shared with the world, responses were effusive from critics, audiences and fellow filmmakers alike. It received rave reviews. It was chosen over hundreds of other options for the Toronto International Film Festival’s audience award, which is often a harbinger of Oscar success. And it was hailed by no less a legend than Jane Fonda, at the recent Palm Springs International Film Festival’s Awards Gala, as “a perfect film,” who added, “I feel so proud of being in the business of moviemaking when I see a film like Hamnet.”

Gonda passed along comparably high praise from someone whose default position is normally silence: his mentor, Malick, who had recently sent him an email reacting to the film, and told him that he had permission to share it with his colleagues, which he did for the first time during this interview: “Dear Nic, I watched Hamnet last night. My heart was in my throat the whole time. I felt shaken to the core. It was searing, wondrous. What a magnificent piece of work. Please tell Chloé and the whole filmmaking team what you all know so well: what a wonderful film you all have made, full of love, tenderness, humanity and compassion. Love, Terry.”

Added Gonda, “As long as I’ve known him, I’ve rarely seen him speak up like that.

The conversation closed with Spielberg emphasizing, as he did while accepting the best picture Golden Globe for Hamnet, the importance of seeing the film in a theater with others: “When you’re seeing a movie — especially a movie like Hamnet, which deals with love and loss and hope and happiness and deep grieving — when you put that out there in a theater, everyone becomes a community… all of us become brothers and sisters, and there are no differences between us because we are all in communion with the story that Chloé has told. And that’s why films like Hamnet deserve a theatrical release — not just releasing it into the world with clusters of five or six people sitting around a living room watching television, but altogether in the great unknown of a dark movie house. In that sense, Hamnet gives me a lot of hope.”