As I write, the kidnapping of Nancy Guthrie, the 84-year-old mother of NBC’s Today host Savannah Guthrie, from her home in Tucson AZ, remains unsolved and unsettling. Little is known for sure other than that a beloved matriarch vanished in the dead of night and that recently released Nest Cam footage of a suspect may lead to a break in the case and, one hopes, the redemption (the Puritan word seems appropriate) of the captive.

What is known is that the Guthrie abduction has mesmerized the American public as no true crime case has since — what? The 16-month-long delirium that was the O.J. Simpson case in 1994-1995? Unlike the vulgar spectacles anent OJ-TV, however, the Guthrie case has engendered a heartening degree of public sympathy and sensitivity, perhaps because of the double dose of pain unique to the crime of kidnapping, which tortures two sets of victims: the captive and the family that wants her back.

Americans have been feeling that media-forged emotional bond since the first convergence of all the elements of electronic-age news coverage. It too was a kidnapping case, in fact the case that warrants the oft-used hyperbole, the crime of the century: the kidnap-murder of the twenty-month-old son of aviator Charles A. Lindbergh and his wife and copilot Anne Murrow Lindbergh.

In 1932, before snuggling up to the Nazis and serving as the most enthusiastic spokesman for the isolationist and antisemitic American First Committee, Lindbergh was the most admired — adored is not too strong a word — man in America. His non-stop solo flight from New York to Paris on May 20-21, 1927, inspired a wave of adulation that has never been equaled. “Grant after Appomattox? Dewey after Manilla Bay? The troops after World War I?,” recalled Fred Allen, looking back in 1956, still in thrall. “Lindbergh after Paris surpasses them all.” The Lone Eagle was 25 years old, slender, matinee idol handsome, and authentically heroic. No wonder the nation swooned.

In 1929, “America’s uncrowned prince” met his princess — the pretty, bookish, and brilliant Anne Morrow, who became his copilot and radio operator. On June 22, 1930, she gave birth to a son — Little Lindy, the Little Eaglet. On August 5, 1932, when newsreels screened the first pictures of the baby in his stroller, audiences cooed and applauded.

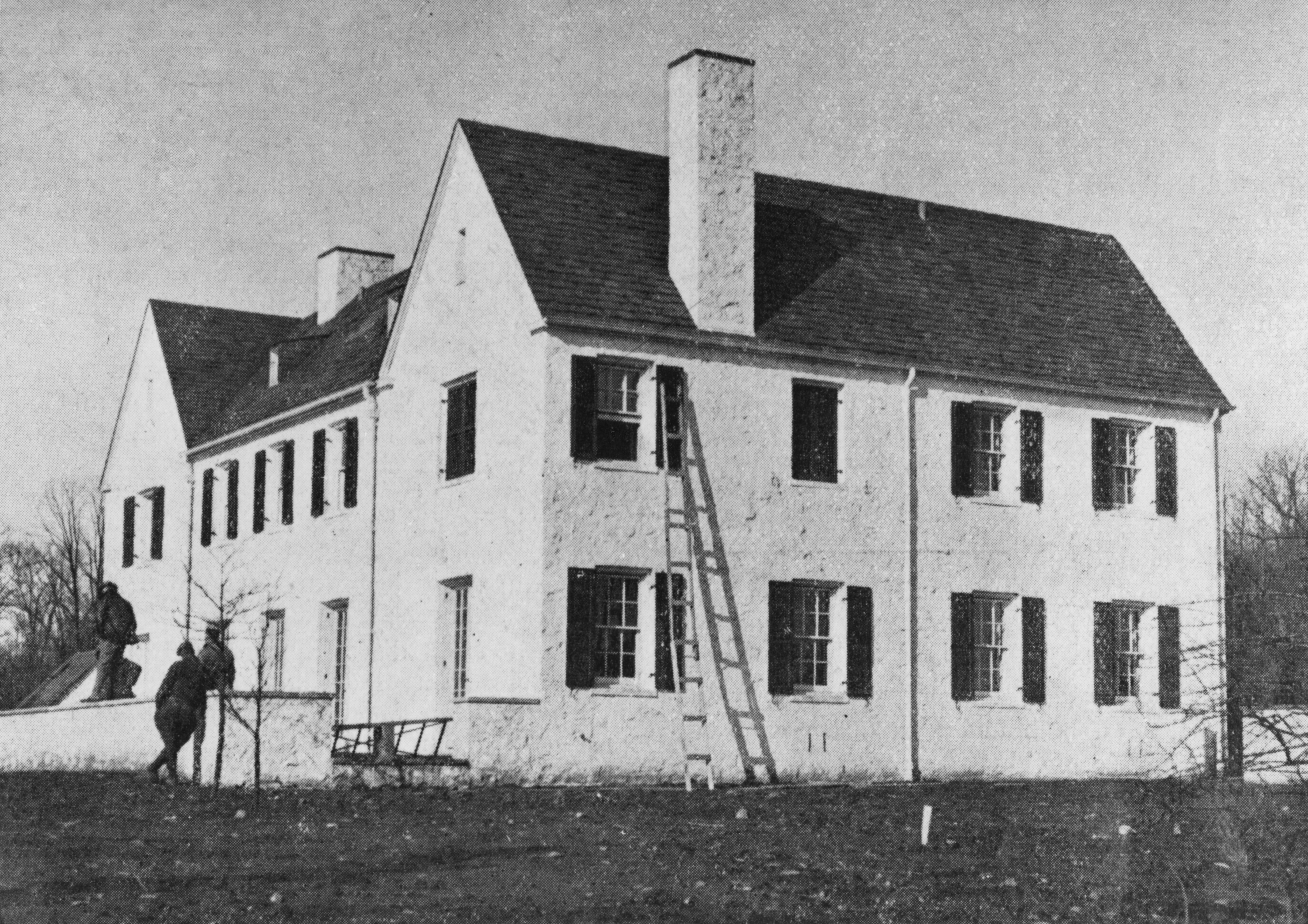

On the chilly night of March 1, 1932, the unimaginable happened. The baby was kidnapped from his crib in the second-floor nursery of the Lindbergh home in Hopewell, NJ. The kidnapper had climbed to the nursery with a homemade ladder, later found on the grounds with a broken rung. He (no one for a minute thought the perpetrator was a woman, though many assumed a female accomplice would be necessary to care for the baby) left a handwritten ransom note demanding $50,000. The note was signed with a strange symbol at the bottom to verify the kidnapper’s identity in future communications.

At 10:46 p.m. that night the New Jersey State Police sent out a teletype: “Colonel Lindbergh’s baby [has been] kidnapped.” The three branches of the mainstream media of the day sprung into action. Newspapers, heretofore the go-to source for news and information, scrambled to put out extras “hot of the presses,” but no matter how hot typeset print could compete with the speed of electricity. By 1932, roughly 40 percent of American households owned a radio (higher in urban, lower in rural areas). The public appetite for news about the Lindbergh baby was so ravenous that Americans would not wait for the next day’s newspaper.

Radio broadcast hourly bulletins on the case and interrupted entertainment with urgent developments. To get the latest news, Americans now “reached for the dial” and stayed “glued to the set.” Both phrases survived into the television age before becoming anachronisms in the age of digital media. However, the instinct first acquired in 1932 has remained with us ever since: when we are hungry for information and want it now, we turn on an electronic device and stay plugged in.

The third pillar of the media triad was also newly arrived: the sound newsreels, which in 1930 had acquired the gift of speech — for voiceover commentary and eyewitness interviews. Cameramen rushed to Hopewell, arrived in the dark, set up their equipment, and waited for daylight. Along with the newspapermen (and women: one of the first on the scene was Laura Vitray, a hardened beat reporter for the New York Evening Journal) and radio journalists (they were no longer mere announcers), they trampled on the grounds and pawed the evidence. There was no yellow police tape.

Despite pleas from the newsreel cameramen, the Lindberghs refused to make an on-camera appeal to the kidnapper, but Anne released to the press a heartbreaking note with the baby’s special diet and medicines: “One half cup of prune juice after his afternoon nap,” she instructed. The contents were printed in the newspapers and read on radio.

When the cameramen asked Lindbergh if he had any home movies of the baby, he recalled that a relative had taken some of the baby’s first birthday party. The footage was turned over to the newsreel outfits and copied and distributed with unprecedented speed. The all-points bulletin was playing in New York and New Jersey theaters that very night, March 2, 1932, the first time the newsreels had incorporated home movies into their issues — it was basically the first Amber Alert. “I’d like to have that kidnapper alone for just about four minutes,” growled Universal Newsreel announcer Graham McNamee. When the pictures of the boy in his crib unspooled in theaters, many women quietly wept.

Meanwhile, off screen, off the airwaves, and not reported in the press (journalists were terrified that a careless word might endanger the baby), negotiations were being conducted with the kidnapper by an oddball emissary who had injected himself into the case. Out of nowhere, an eccentric 71-year-old retired Bronx school teacher named John F. Condon had offered himself as an intermediary — and the kidnapper took him up on the offer. Condon — under the moniker “Jafsie,” from his initials JFC — posted ads in a Bronx newspaper to communicate with the kidnapper. He met the alleged kidnapper — here the details sound like B movie — in two different Bronx cemeteries, at night. The man, whom he called “Cemetery John,” had prominent cheekbones and a German accent. In the second meeting, Condon gave the kidnapper $50,000. Over Lindbergh’s objections, agents from the Department of the Treasury, not the FBI, had recorded the serial numbers of the ransom bills. The bills were in “gold certificates,” a currency soon to be taken out of circulation.

No proof of life had been demanded — or, logically, could it have been. A phone call would be meaningless and a photograph could be traced. Proof of abduction would have to suffice. The kidnapper mailed Condon the baby’s gray night suit, worn the night of the kidnapping. “I wonder why they went to the trouble of having it cleaned?” puzzled Lindbergh.

While the public waited anxiously, and this may be hard to credit in retrospect, no one seems to have imagined that the worst-case scenario was a possibility. In The Snatch Racket, published as the case unfolded, journalist Edward Dean Sullivan warned that “only too often the victim is dead when the ransom demand is made.” But the death of Little Lindy was too awful to contemplate — certainly to write about in print or utter on the radio. Towns in New Jersey made preparations for civic celebrations for when the baby was redeemed: fireworks, a parade, church bells tolling.

On May 12, 1932, in the late afternoon, New Jersey State Police Chief Colonel Norman Schwarzkopf gathered journalists in a garage at the Lindbergh home and shared the news no one wanted to hear. The baby’s body had been found less than five miles from the Hopewell estate. Radio bulletins broke into entertainment programming and within thirty minutes the New York Daily News had an extra edition on the street. “Baby Dead” was the blunt headline. In Times Square, stricken crowds stared up at the electric banner on the New York Times building. Some motion picture exhibitors pulled the newsreel reports from their programs: it was too upsetting for their patrons. In 1939, looking back on the moment, the cultural historian Frederick Lewis Allen observed, “A great many Americans whose memories of other events of the decade are vague can recall where and under what circumstances they first heard that piece of news.” Will Rogers, normally a humorist, captured the mood. “One hundred million people lost a baby,” he wrote. “One hundred twenty million people cry one minute and demand vengeance the next.”

Vengeance was a long time coming. For the next two and half years, the case was cold, but emotions were still raw. On November 26, 1933, in the last public lynching in California history, a mob took two kidnap-murderers from the San Jose jailhouse and strung them up in St. James Park. California governor James Rolph Jr. said they had it coming.

Across the country, every banker and cash register operator kept a list of the serial numbers at hand in case a ransom bill turned up. Finally, on September 15, 1934, an alert gas station attendant in Harlem got suspicious when a German-accented driver paid for his gas with a $10 gold certificate. He wrote the license plate number on the back of the bill and, when he deposited the money at the bank, the manager got a hit with the serial number.

The vehicle was owned by thirty-four-year-old Bruno Richard Hauptmann of the Bronx, an illegal German immigrant with no obvious income stream. $13,750 in ransom money was found hidden in his garage. At a press conference filmed by the newsreels, New York Police Commissioner John F. O’Ryan, FBI director J. Edgar Hoover, and Colonel Schwarzkopf announced the long manhunt was finally over. “The mystery of the Lindbergh kidnapping has been solved,” said O’Ryan.

On January 2, 1935, the Crime of the Century gave way to the Trial of the Century. Held in Flemington, NJ, the proceedings were presided over by the fair-minded, no nonsense Judge Thomas W. Trenchard. The ambitious New Jersey State District Attorney David T. Wilentz was the prosecutor; he was determined to put Hauptmann in the electric chair. The defense attorney was the colorful Edward J. “Big Ed” Reilly, his fee paid for by media mogul William Randolph Hearst in exchange for exclusive access to his client. Namebrand reporters came to Flemington for a syndicated byline, including Walter Winchell, Ring Lardner, and Hearst’s favorite “girl reporter,” forty-year-old Adela Rogers St Johns. A veteran crime reporter and self-described “sob sister,” St. Johns filed the best coverage of the 32-day day trial: 1500-2000 words a day on deadline; city editors would wait by the teletype machine for her copy to roll in. At one point, she looked over at Hauptmann, concluded he was stone guilty, and confided she’d go to the Trenton State Prison and pull the switch herself.

Radio was not permitted to wire the courtroom for live broadcasts, but the testimony was reenacted on the air at night and lawyers offered expert commentary (most notably Samuel Leibowitz, famed defender of the Scottsboro Boys). Surprisingly, Judge Trenchard permitted the newsreels to install a low-noise camera in the courtroom balcony, but only on the condition no filming was done during actual testimony when the court was in session. However, when Lindbergh, Anne, Condon, and Hauptmann took the stand, the cameramen could not resist surreptitiously turning on the camera and betraying the judge.

The sensational trial footage was released into newsreel theaters on February 1: the first time that live sound-on-film courtroom testimony was widely beheld, the original Court TV. At the Embassy Newsreel Theater in New York, the footage played on the hour to standing room only crowds from 10 a.m. to midnight.

Hearing of the double cross, Judge Trenchard and DA Wilentz went ballistic: they demanded the newsreels be taken off the screen immediately. Three of the newsreel outfits — Fox, Paramount, and MGM — sheepishly complied. Pathé and Universal News however told the judge to stuff it: their defiance marked a major assumption of First Amendment protection for motion picture journalism. “I don’t see how anyone could withdraw the subject and still have respect for their medium,” said Pathé editor Courtland Smith.

Offering a curriculum today’s web sleuths would appreciate, the Lindbergh trial also had readers and listeners doing deep dives into forensic science — handwriting analysis, banking records, and testimony from experts in exotic fields such as dendrology, the study of wood (an expert testified that the wood used in the incriminating ladder came from floorboards in Hauptmann’s attic).

Though evidence against Hauptman was overwhelming, he steadfastly maintained his innocence. He was not persuasive. On February 13, 1935, as crowds outside the courthouse shouted “Kill the German! Kill Hauptmann!” the jury rendered a unanimous verdict of guilty with no recommendation for mercy — an automatic death sentence.

On April 3, 1936, at 8:47:30 p.m., Hauptmann died in the electric chair at Trenton State Prison. Of course, neither radio nor the newsreels were permitted inside the death chamber, but from their studios, radio commentators maintained a live vigil until they got final word to announce the execution. “Was Hauptmann `game’?” a reporter asked the warden afterwards. The press always wanted to know whether the condemned man was stoic or had “died yellow.” “He seemed to be very game,” replied the warden.

The Lindbergh kidnap-murder and the Hauptmann trial left a profound legacy on American law, on police procedure, and on the media. In June 1932, Congress passed legislation making kidnapping a federal crime and the next year made it a capital crime; many states followed with similar statutes. The handling of the case by the New Jersey State police was considered so incompetent, even by the investigatory protocols of the day, that J. Edgar Hoover and the FBI would henceforth be given presumptive jurisdiction over kidnapping cases. Radio journalism came of age, hiring its own commentators and beat reporters to cover breaking news, no longer relying on newspaper copy. The newsreels also realized that motion picture journalism could do more than issue weekly updates on the progress of the Dionne Quintuplets.

Yet the saturation media coverage of the case so distressed the American Bar Association that the group adopted a bylaw, Canon 35, forbidding cameras in the courtroom, a ban that remained in effect until the 1970s (which is why the criminal and political trials of the 1960s are visually remembered in courtroom sketches). In Hollywood too there was blowback: the Hays office ordered a total ban on any motion picture scenario built around child kidnapping, an edict rigorously enforced after 1934 (Not until Ransom! in 1955 would the ban be lifted.)

Every true crime story that has attracted the emotional engagement of the American public since, including the one today, has followed the media playbook from the Lindbergh case.

Thomas Doherty is a professor of American Studies at Brandeis University and the author of Little Lindy Is Kidnapped: How the Media Covered the Crime of the Century.