My earliest Sundance memory isn’t a party or a deal — it’s a film. I was in my 20s when I first traveled to Park City with friends, not yet knowing how much that trip would shape my life. We happened upon a screening of Sex, Lies, and Videotape, andI was riveted. That film, now recognized as a watershed moment, helped revolutionize the independent film business. Watching something so raw and quietly radical unfold on screen was jaw-dropping for a young woman beginning her career in the industry and witnessing something so personal and revelatory marked the beginning of what would become both a lifelong career and an annual pilgrimage to the Sundance Film Festival.

I was living in New York at the time, and I remember the feeling of being dropped into this little snow globe of a town that felt like the center of the universe. There were fewer distractions in those early days — no constant buzzing in your pocket. I flew into Salt Lake City, made my way to Park City, camped out with friends and hopped on the shuttle to get from one theater to the next. If you were lucky, someone had a car, and you’d pile in together. But truth be told, I loved the shuttle, standing shoulder-to-shoulder with strangers and talking about films like it was the only thing in the world that mattered. Because for a week, it kind of was.

Pretty quickly, Sundance became a significant part of my life — not just professionally, but personally. I attended the festival while seven months pregnant with a film I produced, Twin Falls Idaho. That year marked a turning point: I left the international sales world to become an independent film agent at the former William Morris Agency alongside Cassian Elwes, where we built a global packaging and finance department — an approach many agencies soon followed and one I brought to help build UTA’s Independent Film Group a decade later.

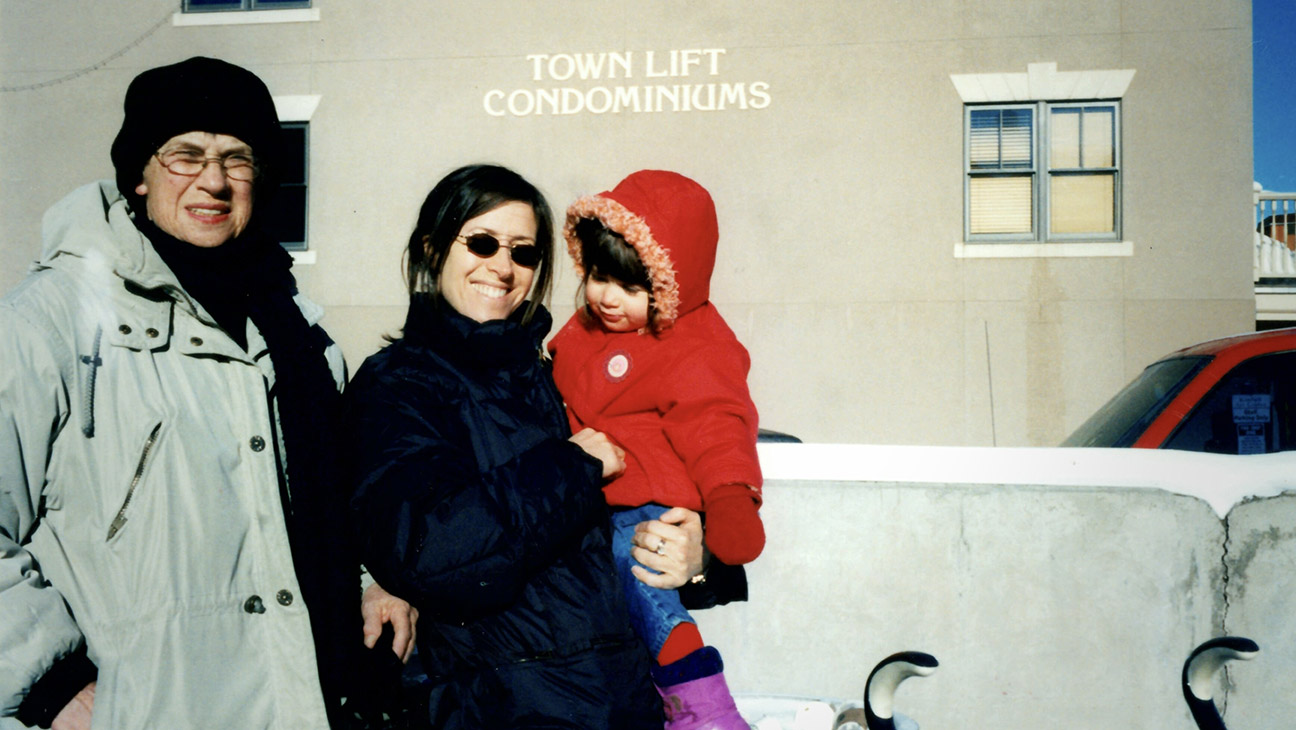

Not long after, my Sundance became even bigger. Once my daughter was born, she came with me to Sundance every year for the first decade of her life, along with my parents. Park City became our yearly family ritual. My parents, New Yorkers and devoted moviegoers, fell into its rhythm, while my daughter, Bella, had her own version of Sundance, like her first time skiing at Deer Valley at four years old, and days spent with producer Julie Yorn’s daughter, like it was winter camp. It was work, but it was also this small, special world for the people I loved most — like the year my father bumped into the late film critic, Roger Ebert, and proudly told him his daughter had produced Twin Falls Idaho, as if he were in the know, even though it premiered the year before!

We stayed in the same place year after year — the Town Lift Condos at the base of Main Street. It was practical, as you could walk to and from Main Street, and it later became our home base for the UTA Indie Film Group. We’d take over a floor and have meetings all day. People coming in and out. Agents camped out. Filmmakers dropping by. It was our little hive.

That’s one of the things that made Sundance so special, all the behind-the-scenes frenzy that only happens when trapped together in a tiny mountain town. Many of us remember the late-night bids and negotiations that stretched into the next morning. No email chains, but in-person negotiations. It was equal parts strategy session and endurance sport. And years later, when cell phones became a given, deals happened in the most Sundance way possible — at the top of a ski resort where, ironically, the reception was best.

And then there are the stories that sound made up until you remember, “No, it really was like that.”Like hiding from distributors to avoid being pressured to close or a bidding that turned so contentious it eventually spiraled into a physical confrontation in front of a restaurant on Main Street.

Sundance back then was high-stakes, high-emotion and fueled by a kind of cabin-fever energy. Put a group of ambitious people in a small town, running on no sleep and a ticking clock and things occasionally got dramatic.

It sounds insane, and it was, but that intensity was oddly part of the magic. Sundance has always had a way of compressing time. One screening can flip everything overnight. There is nothing like a screening filled with reverberating laughter, when you smile to yourself thinking, “They get this film.”

In my 30-plus years of going to Sundance, I’ve seen careers break in ways that are undeniable, and I was fortunate to be involved with some truly memorable films along the way. Early discoveries like David Slade’s Hard Candy (2005) and critically acclaimed films like The Woodsman (2004), Half Nelson (2006), Frozen River (2007), Blue Valentine (2010) and Margin Call (2011) along with Lee Toland Krieger’s debut Celeste and Jesse Forever (2012), written by Rashida Jones and Will McCormack, and Michael Showalter’s The Big Sick (2017), written by Kumail Nanjiani and Emily V. Gordon. Other highlights were Palm Springs (2020), which we sold for a record-breaking number, and Marielle Heller’s The Diary of a Teenage Girl (2015), where we witnessed a filmmaker’s voice landing fully formed and the unmistakable sense that you’re watching the start of a real career.

Documentaries have also been central to my Sundance experience. Films like Hoop Dreams, Murderball and March of the Penguins sparked a lasting passion for the form, which led me to work on films like The Cove (2009) and Bryan Fogel’s Icarus (2017), both of which went on to win the Academy Award. And then Jeff Orlowski’s The Social Dilemma (2020), Maite Alberdi’s Oscar-nominated The Eternal Memory (2023) and Josh Greenbaum’s Will & Harper (2024), each a reminder that documentaries can move the world in real time and being part of that impact is deeply personal.

What distinguishes Sundance from other festivals is that it’s always been a true discovery engine. That’s Robert Redford’s legacy. The festival, as we know it, was designed to nurture emerging voices, and Park City, with its small-town intimacy, made that mission feel tangible.

The festival, like the business itself, has been in constant flux. And as Sundance expanded, Park City inevitably began to outgrow its small-town footprint.

Which brings us to Boulder.

Many people have asked me what I think about Sundance in Boulder. To me, it will be more of a Sundance 2.0, not Sundance “moving”. It’s a new chapter, and it’s time to embrace the change as the world evolves. Park City will always be the Egyptian, Eccles, Main Street, The Eating Establishment, Grappa, the Library and even the Holiday and Yarrow. That mythology belongs to that town. But the spirit of Sundance is something we all hope and believe can be portable. Ideally, Boulder holds it in a new way, reaching a new and vibrant younger audience at the same time.

If Sundance gets this next chapter right, five years from now we’ll still be talking about what has always mattered: discovery, new voices, films that break through and careers that get launched. That’s the hope and the challenge.

Boulder won’t replace Park City, but it can create its own kind of magic. The festival’s heart can thrive anywhere it’s nurtured. If we carry that purpose forward, Sundance won’t just be a new location — it will be a continuation of a story that has always been about seeing films, discovering voices and witnessing careers take root in real time.

My parents are no longer here. My daughter is grown. But Park City holds so much of them for me, from the photos, the rituals, the memories, the bear statue on Main Street and the condo that became our home away from home. Sundance hasn’t just been a festival where I worked; it’s a place my family has lived alongside me.

As this transition happens, this is what I hope never changes: The feeling that, for at least one week at the start of the year, the movies come first, discovery is still alive and the future of independent film can still begin in a theater as the lights go down.

Rena Ronson is partner and head of UTA Independent Film Group and a 30-year Sundance Film Festival veteran.