In the mid-1980s, around the time The Goonies delighted moviegoers with its story of pirate treasure, the 39-year-old Cuban American archaeologist Roger Dooley was deep in a Byzantine Spanish archive, hunting for a treasure ship of his own. As an archaeologist, he didn’t particularly care about treasure. But his boss did: Dooley was working for a state-run Cuban company called Carisub, formed by Fidel Castro to extract riches from the sea, including from the many Spanish wrecks thought to lie around the island nation.

While under the archive’s vaulted ceiling, he chanced on long-hidden documents that contained clues to perhaps the greatest sunken treasure of all time: the legendary galleon San José, which sank in battle with a British squadron off Colombia in 1708, along with 600 men and a cargo of gold and silver estimated to be worth billions of dollars. It has been called the Holy Grail of Shipwrecks.

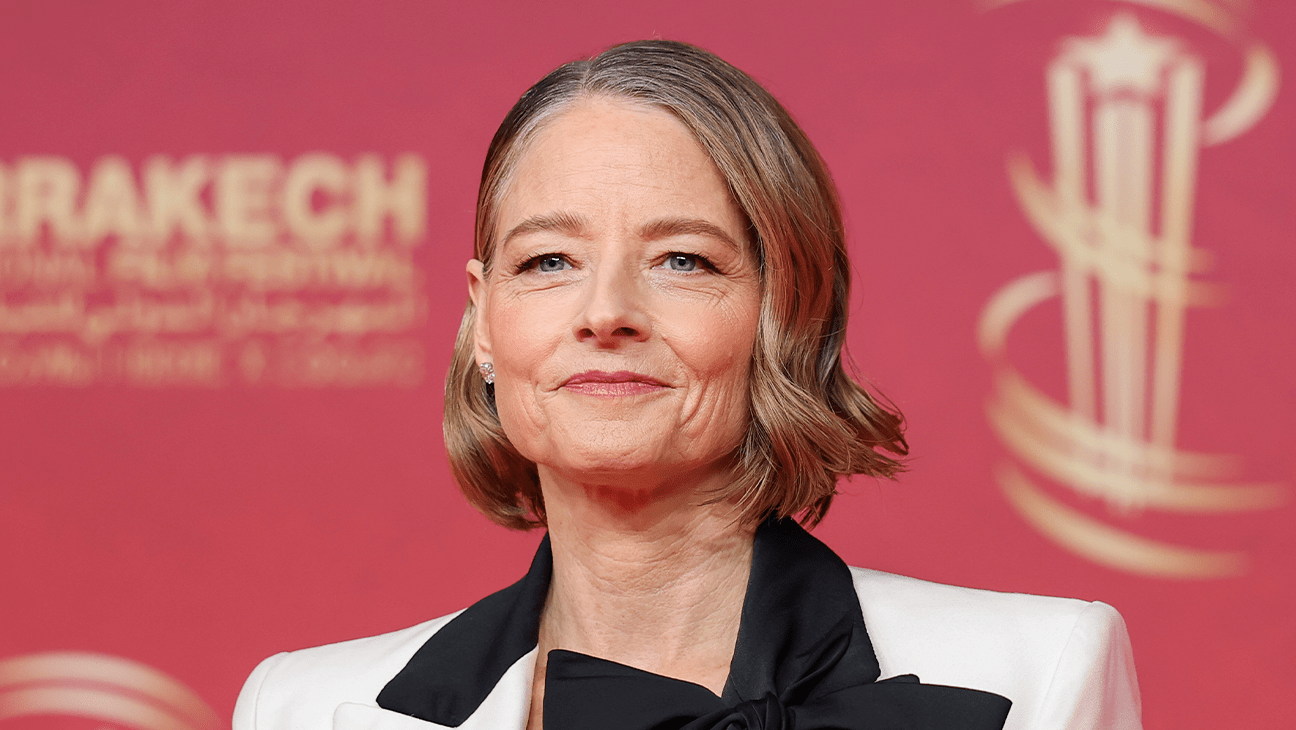

“That’s the day I fell in love,” Dooley told me in one of our many interviews for my new book on the galleon, Neptune’s Fortune (Jan. 27). Being outside Cuba’s waters, the San José would be of no use to Castro. But the notion formed in Dooley’s mind that he would one day find it.

The search would take him more than 30 years, during which he led a parallel career as a filmmaker. His two passions, it turns out, would complement one another: Both shipwreck hunting and moviemaking are fundamentally romantic pursuits with low odds of success.

Dooley’s love of movies dated to his all-American childhood in Brooklyn and his excursions with his mother to Times Square picture houses in the 1950s. His family moved to Cuba in 1957, when his stepfather got a job as a manager of the Havana Hilton, the hottest new hotel in the gleaming, mob-run Caribbean city.

Cuban TV, before Castro’s New Year’s coup of 1959, was American TV. Young Roger Dooley was particularly enamored with the new hit series Sea Hunt, starring Lloyd Bridges as a former Navy frogman who solves undersea crimes. The show triggered a yearning for underwater adventure in Dooley, who would go on to become the country’s first maritime archaeologist.

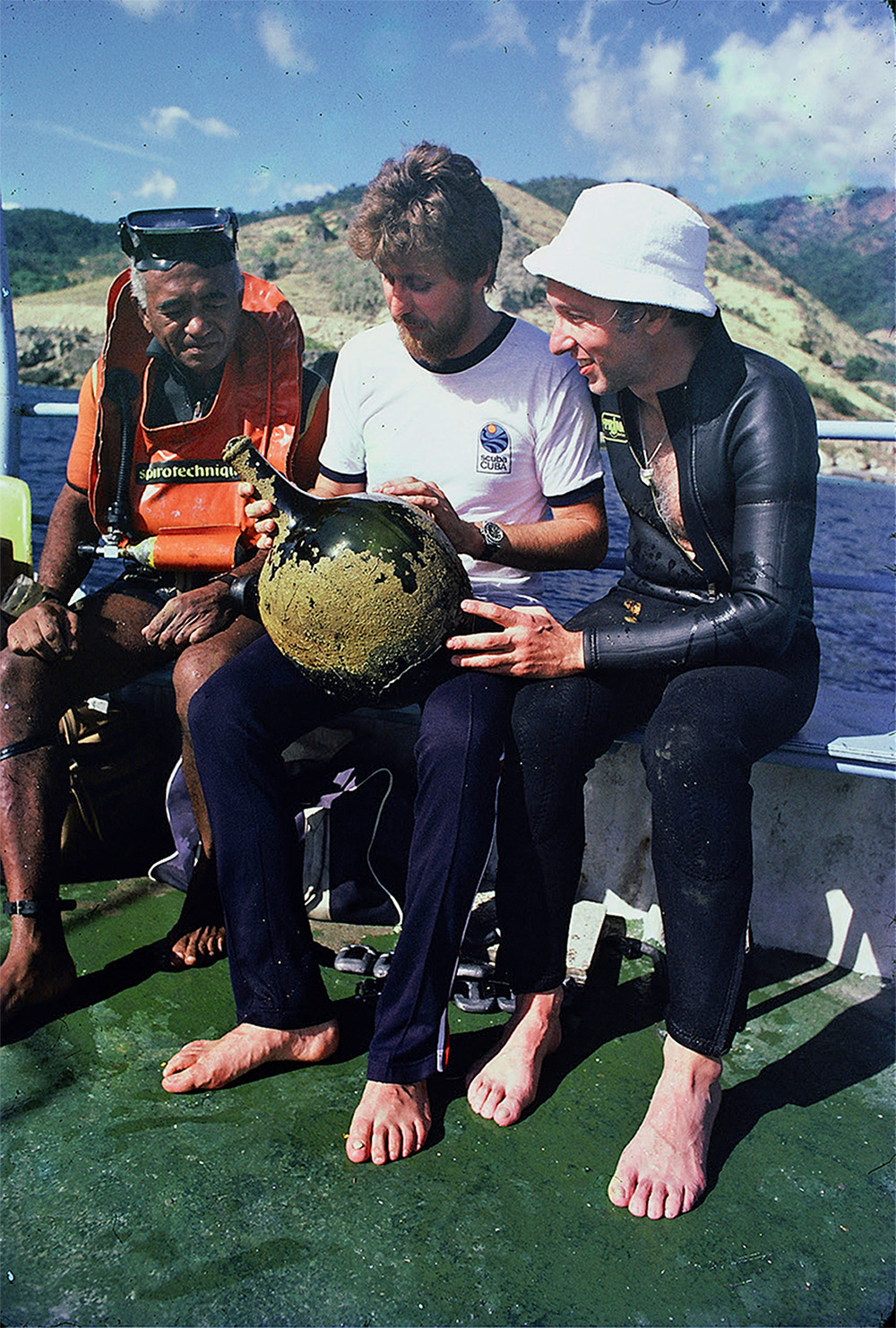

In the late 1970s, he befriended Hollywood cinematographer Al Giddings, who had made a name for himself as a DP on the hit 1977 Nick Nolte treasure-hunting film The Deep and would shoot the 1981 Bond movie For Your Eyes Only, 1989’s The Abyss and 1997’s Titanic for James Cameron. Giddings was looking to shoot a movie about the shipwrecks in Cuba’s forbidden depths, and nobody knew those better than Dooley. The archaeologist was Giddings’ guide to Cuba’s underworld.

“During my first deep dive, I discovered a huge unbroken wine bottle, a fine museum candidate, thanks to Roger,” Giddings, 89, tells THR. “It sits in my living room today, a treasured memory of Roger and our special adventures.”

All the while, Dooley peppered Giddings with questions about filmmaking. Giddings’ lessons would prove invaluable when, in the mid-’80s, Castro called on Dooley — his man underwater — to co-direct a documentary showcasing Cuba’s reefs.

Dooley’s film, Island of the Blue Treasure, was a success, earning a top prize at the San Sebastian Underwater film festival. Even as he continued his obsessive personal research into the San José, he decided to reinvent himself as a filmmaker. He put his newly acquired cinematic skills to use as a coordinator of underwater photography on The Summer of Miss Forbes, a 1988 TV movie written by the great Colombian novelist Gabriel García Márquez.

But Dooley wasn’t satisfied remaining in the cinematic backwater that was 1980s Cuba. It’s a testament to his irrepressible optimism that despite being stuck on the island, under totalitarian rule, he dreamed of making it in Hollywood. In the ’90s, he met in Havana with several prominent producers, among them Sony Pictures CEO Peter Guber and Gary Foster (Sleepless in Seattle), who worked with Dooley on an underwater adventure film about Cuban smugglers. Dooley inevitably had his own ideas to pitch them, most notably the true story of a sunken Nazi U-boat he was searching for off the Cuban coast. “He oozes charisma,” recalls Foster. “He’s a salesman, a hustler, a passionate guy who spoke really fast. We loved him immediately.”

The projects went the way of most in Hollywood — nowhere. But with the help of well-connected American friends, Dooley managed in 1997 to flee Cuba for the U.S. Able to travel freely once again, he continued his pursuit of the San José, collecting clues in archive after archive. By the 2010s, he was pretty sure he knew where the elusive galleon lay, at a depth of about 600 meters.

He would need to convince powerful people to grant him the authorization, financing and technology to search for it. And if his cinematic education had taught him anything, it was how to tell a good story.

“I know about narrative,” Dooley tells me. “I know how to put together what people love. Intrigue. Mystery. Treasure and all that shit.” When pitching backers, he made sure to emphasize the amount of gold and silver they stood to gain. By contrast, when pitching the Colombian government for a search permit, he emphasized the historical importance and the glory such a discovery would bring the country. In every case, he kept his audience rapt.

In November 2015 — financed by a British hedge fund titan and armed with marine robotics from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute — Dooley and his team found the remains of the fabled San José. A scattering of gold coins gleamed on the seabed, hinting at the vast riches below. Ever the filmmaker, Dooley made sure cameras were rolling.

But for all the triumph Dooley felt in the moment, his name appeared nowhere when the discovery of the San José made international headlines. The Colombian government declared his involvement a national secret, essentially writing him out of his own story.

A year later, as a parting gesture, outgoing Colombian president Juan Manuel Santos at last publicly credited Dooley. But since then, so many factions have been fighting over ownership of the wreck — from the backer to Spain to Colombia to the descendants of the Indigenous tribes in Bolivia whose ancestors had been forced to mine the silver from their own lands — that the galleon and its treasure have been locked in limbo, with the first few artifacts having been raised only late last year.

In the decade since his discovery, Dooley has tried to fight his way back into the saga of the San José. As he waits, he has a movie to pitch, about a Nazi U-boat off Cuba: “I hope Tom Hanks reads your article.”

This story appeared in the Jan. 15 issue of The Hollywood Reporter magazine. Click here to subscribe.