A mother-son road movie more laced with humor than laden with trauma, Hot Water marks a warm and sensitive, if not entirely satisfying, debut feature from Ramzi Bashour.

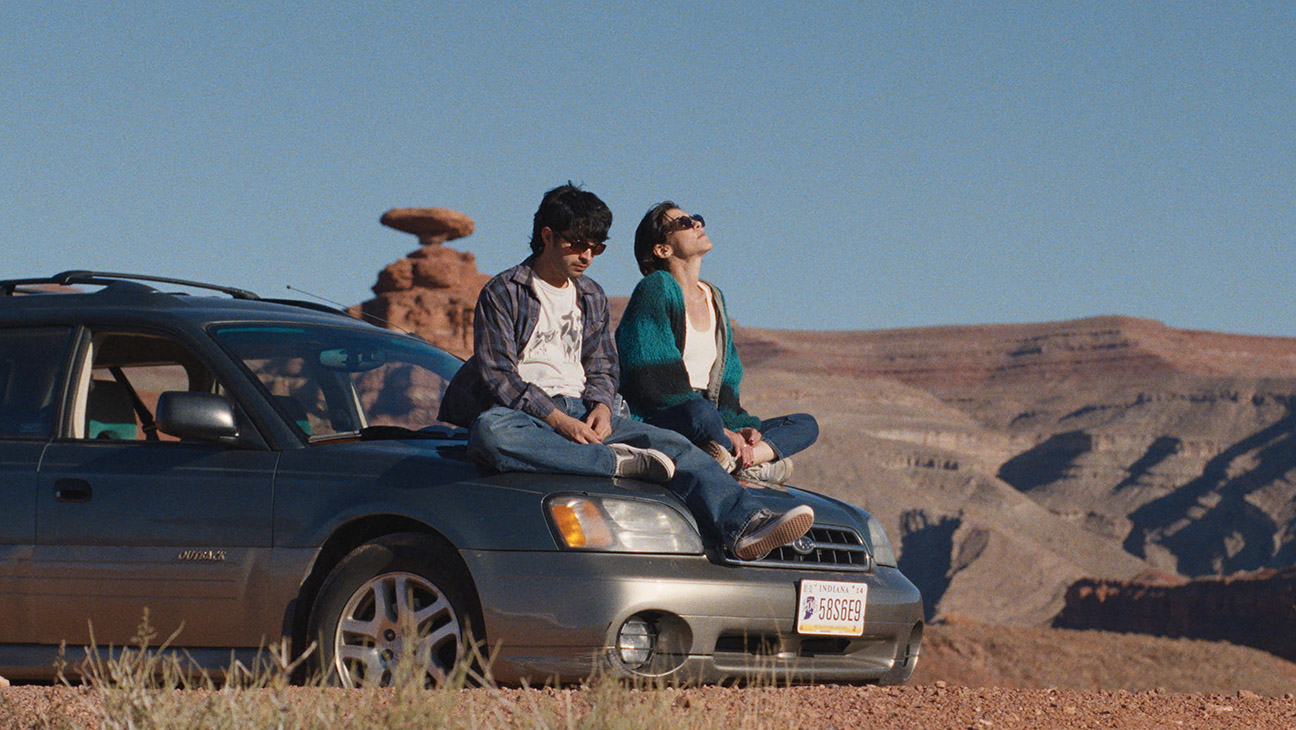

There’s an undeniable familiarity that nips at the heels (or wheels?) of the film as it traverses classic American landscapes alongside its protagonists, a tightly wound Lebanese woman (Lubna Azabal) and her turbulent, U.S.-raised teenager (Daniel Zolghadri). We’ve been here before — in this situation, with these types, against these backdrops. Every year at Sundance, to be exact.

Hot Water

Warm and sweet, if not entirely satisfying.

Luckily, the leads are good company, and there’s just enough in Hot Water that feels fresh and personal to lift it above dreaded indie staleness. Bashour has a light touch, an aversion to exposition, histrionics and overt sentimentality, that serves the material well.

If the film’s modesty, its glancing quality, is a strength, it’s also a limitation. There’s a nagging sense that the writer-director is just skimming the surface of his characters, their relationship to each other and to the country they live in. The Syrian-American Bashour knows these people and their story in his bones — the movie has several autobiographical elements — but he doesn’t always translate that depth of understanding to the screen.

The problem is an excess of tact — a reluctance to really dive into the ideas simmering here, to allow the central pair’s experience of forced proximity on the open American road to palpably complicate or illuminate their respective identities and points of view. As pleasant, and occasionally poignant, as Hot Water is, it never commits fully to either its comedy or the emotions that often feel assumed rather than earned. And Bashour is not yet a sophisticated enough filmmaker to conjure richness of meaning with the narrative and visual economy of a Debra Granik, a Kelly Reichardt or an Eliza Hittman, to name (perhaps unfairly) some American neo-realist touchstones to emerge from Sundance.

Hot Water is Bashour’s third collaboration with writer-director Max Walker-Silverman: The latter is a producer here, while Bashour composed the music for Walker-Silverman’s quiet soul-stirrer A Love Song and edited his more ambitious but less affecting follow-up, Rebuilding. Theirs is a softer, fuzzier regional cinema than the aforementioned auteurs’ work, infused with a wistful belief in the redemptive promise of American community, as well as a reverence for the natural beauty we take for granted.

In A Love Song and Rebuilding, the protagonists are rooted to the land in a way that Hot Water’s Layal (Azabal), a foreign-born professor of Arabic at an Indiana college, is not. Layal’s ambivalence toward her adopted home is a note of discordancy that the film never taps for its full dramatic potential — an example of how Bashour’s gentle approach veers toward a sort of frictionless amiability. The movie is full of fleeting interpersonal clashes, but deeper social and political undercurrents are left largely unexamined.

The catalyst in Hot Water comes when Layal’s son Daniel (Zolghadri) attacks another student with a hockey stick, getting himself expelled from the high school that’s already held him back twice. Out of options and patience, Layal decides to drive Daniel out to Santa Cruz to live with his father and finish out his senior year. Cue the procession of sunbaked cornfields, plains dotted with wind turbines, snow-capped mountains, craggy red rock, and the neon pageantry of the Vegas Strip. The expected stops at motels, diners and gas stations are punctuated by Layal’s fraught phone calls back to Beirut, where her sister reports on their mother’s declining health.

Hot Water ambles along agreeably, buoyed by the believably fluid dynamic between Layal and Daniel. The filmmaker and his performers don’t overplay the fractiousness; there’s tension in their relationship, but also teasing affection, respect and a push-pull of aggravation and amusement that is the near-universal dance of parents and teenagers. Daniel gets a kick out of winding his mom up and watching her go off; she chastises him for bad choices and ribs him for not speaking better Arabic. Bashour and DP Alfonso Herrera Salcedo favor straightforward two-shots to showcase that interplay, rather than close-ups capturing instances of individual reflection or realization.

“Why are you so tense and bummed all the time?” Daniel asks Layal, a question that hints at the gulf that separates this middle-class American kid and his immigrant single mom. He has enjoyed the privilege of nonchalance, of messing up, while she has endured the stress of providing a good life for her son while navigating cultural bewilderments like “chicken-fried steak” and students demanding do-overs on botched oral presentations.

I could have happily watched a whole film about Layal’s on-campus life teaching Arabic to mostly white students. A priceless, too-brief scene of her coaching a smiling, square-jawed bro through some challenging pronunciation indeed suggests Bashour doesn’t necessarily recognize what his most distinctive material is. Ditto a glimpse of Daniel, shirtless, rehearsing pick-up lines in the mirror — a seemingly throwaway moment that’s slyer and more intimate than much of the rest of the movie.

Tossing Layal and Daniel into a car and onto the road is perhaps the least interesting, and certainly easiest, way into this story, allowing the filmmaker to push them into confrontation with each other, and with America, rather than coaxing out conflict organically. To his credit, and in keeping with the spirit of the film, Bashour exercises restraint. Layal and Daniel do more bickering than blowing up, and Hot Water doesn’t over-indulge in fish-out-of-water shtick or ambush them with rednecks and racists.

Rather, their journey is textured with odd little encounters, some more compelling than others. Dale Dickey shows up as a benevolent, aphorism-dispensing hippie in an interlude that plays like filler. I preferred the unusually composed kid working the front desk of a motel (“I don’t know, I don’t eat meat,” he notes after referring a hungry Layal and Daniel to a nearby Jack in the Box). Or the run-in with a ripe-smelling hitchhiker, which at first appears to reveal a generational divide between mother and son before uniting them in revulsion.

Azabal (Incendies, The Blue Caftan), alternating among English, Arabic and French with regal impatience, is the kind of performer who can convey fierce love and pride with a mere glance, through sunglasses no less. Layal is perpetually harried — her exasperated “Oh, Daniel!” when he sneezes with a mouth full of carrot cake is perfection — but there’s also a sincere wonderment in the way she looks at her son. Zolghadri, so terrific in Owen Kline’s Funny Pages, flaunts the same gift for note-perfect line delivery here, pivoting seamlessly from sarcasm to authentic feeling and back again.

The leads are so strong that the movie’s reliance on cutesy shorthand — Layal’s constant hand sanitizing and her compulsive clementine-eating as a replacement for smoking, Daniel and Layal exiting their motel room in a slow-mo strut (have mercy, filmmakers: no more slow-mo struts) — registers as an unnecessary distraction. These actors don’t need things in boldface to build out their characters.

The final section, with its minor twist and succession of heart-to-hearts, seems calculated to surprise and stir, but underwhelms. It’s the offhanded bits of Hot Water that land most potently — the ones that hint at aches and yearnings beyond the immediate needs of the plot. “Did you say bye to the house?” Layal asks Daniel as they prepare to pull out of their driveway and hit the road. “The house has no ears, mom,” he mocks. Then, when she gets out of the car to grab something, he gazes up at the home he’s about to leave behind, and whispers: “Bye, house.” That kind of moment, tiny but casually heart-piercing, makes you impatient to see what Bashour does next.