It began, as so many arguments do, at a kitchen table.

They were filming on a soundstage in Utah — Kevin Costner, Wes Bentley and Kelly Reilly — playing out another tense exchange in the Dutton family drama Yellowstone.

But between takes, tensions boiled over. Costner, both star and executive producer, was pushing Bentley to ditch Taylor Sheridan’s script and play the moment his way. Bentley refused. He told Costner that he had signed up for a Taylor Sheridan show, not a Kevin Costner production.

“Kevin didn’t like that, and he lunged at him,” says a source who was present. “No fists were thrown, but they were in each other’s faces, pushing and shoving and just getting hot until they had to be separated.” Reilly, according to one witness, was in tears. Production briefly shut down.

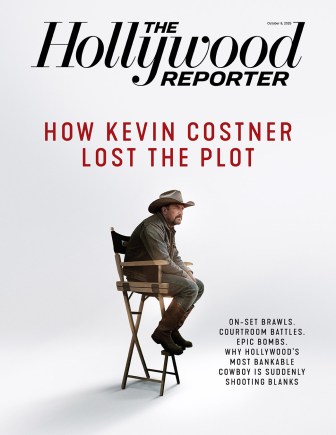

The dust-up — previously unreported — was a tipping point on a set already cracking from creative power struggles and bruised egos. But for Costner, it was merely the latest unfortunate incident in a long series of unfortunate incidents, a career marked by feuds, walkouts, lawsuits, financing fiascos and a growing reputation for being, as one former colleague put it, “impossible.”

There’s a long list of people in Hollywood who swear they’ll never work with Costner again. And they all have their reasons. He doesn’t always pay his bills on time — one since-settled lawsuit alleged hundreds of thousands in unpaid costume fees. He burns through relationships — like his longtime producing partner, whom he sued for $15 million. He ignores advice, even from folks like Steven Spielberg. He rewrites scripts without warning, overrules directors and on more than one occasion has clashed with his co-stars — including Clint Eastwood, Kurt Russell … and Wes Bentley.

All of which raises an obvious question, the one being whispered all across Hollywood right now, even among former allies: What’s going on with Kevin Costner?

The 70-year-old star has always swung for the fences — often literally, in pastoral baseball idylls like Bull Durham and Field of Dreams — with bold, risky choices. And Hollywood has counted him out before, only to be surprised by the resilience of his star power. But now, in the twilight of his career, the comebacks are getting harder to come by. The Oscar-winning director and actor with the most iconic American screen presence since Gary Cooper — the guy responsible for the line, “If you build it, they will come,” who once carried box office megahits like The Bodyguard — is now brawling with his castmates, getting sued by his crewmembers and, in recent months, giving paid keynote speeches at bakery and veterinarian conventions. And behind it all, according to several insiders, are power struggles playing out far from the spotlight — ones that some say have left even Costner himself in the dark.

“It’s sad, and that’s the only thing I can think of,” says a source who’s worked with Costner for over a decade. “I think he got lost in the ether and to this day, I just don’t get it.”

***

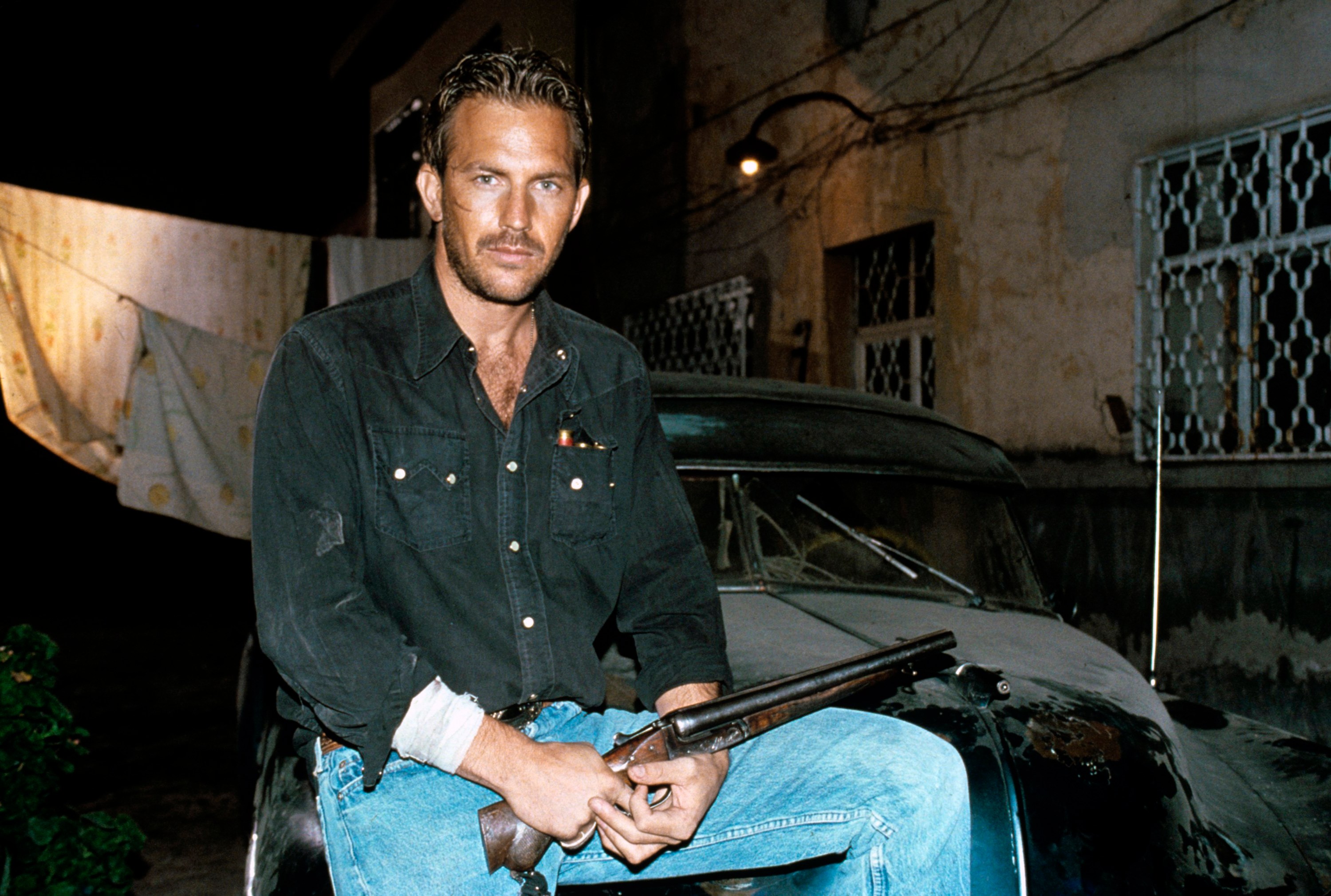

Dances With Wolves had all the makings of an epic disaster. For starters, it was a Western, considered box office poison at the time. But there were also budget overruns, dangerous working conditions and a first-time director in Costner — also producing and starring in the film — who seemed entirely over his head. Before it was released in 1990, Hollywood wags were dismissing it as “Kevin’s Gate,” a none-too-subtle nod to 1981’s Heaven’s Gate, one of the biggest bombs in box office history.

But, of course, the naysayers had it all wrong. After Costner cobbled together its $22 million budget without any major studio investment — Orion Pictures reportedly wrote a check for $11 million while Costner put in $2.5 million of his own money — Dances With Wolves became a decade-defining hit, grossing $424 million, ultimately going on to win seven Academy Awards, including best picture, best director and best adapted screenplay.

It was a cultural phenomenon that single-handedly revived Westerns as a genre and transformed Costner into one of Hollywood’s most bankable stars. Time magazine proclaimed him “The New American hero.” A year later, Rolling Stone put him on its cover under the headline: “An American Classic.”

Costner quickly capitalized on the moment, following up with a remarkable string of hits, starting with Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves, which came out six months after Wolves and grossed $390 million, making it the third-highest-grossing film of that year. That was followed up by Oliver Stone’s historical drama JFK, which grossed $205 million on a $40 million budget. Then came The Bodyguard, which co-starred Whitney Houston, and which grossed $411 million worldwide, making it the second-highest-grossing film of 1992. Suddenly, Costner was considered — alongside Tom Cruise, Arnold Schwarzenegger and Bruce Willis — one of the biggest movie stars in the world.

Then came Waterworld.

In hindsight, it’s easy to see that the 1995 postapocalyptic action film in which Costner plays a mutated mariner living on the fringes of a water-soaked world was a debacle waiting to happen. In fact, at the time, Costner was being warned by no less an oracle than Steven Spielberg. The guy who shot Jaws had reportedly advised Costner and director Kevin Reynolds to avoid filming on the open sea at all costs.

But the warning went ignored and Waterworld — with a budget of $175 million, then the most expensive movie ever made — began shooting around the Big Island of Hawaii in 1994. The production was plagued by hurricanes, tsunami warnings, stinging jellyfish and several injuries — including Costner, who almost died while riding out a storm stranded atop a mast after his safety line had snapped. Things got even worse when the film finally opened on July 28, 1995; it became one of the biggest flops since … well, Heaven’s Gate.

Turns out, that was just the beginning of what would become a long, slow slide for Costner. Two years, later, he released yet another postapocalyptic adventure film, The Postman, which Costner directed, produced and starred in. That expensive film also flopped at the box office and was widely panned (it didn’t help that The Postman opened on the same day as Titanic).

Neither Waterworld nor Postman turned out to be a career killer, but the sheen was diminished. Costner was still a movie star, but he was no longer being offered blank checks and full creative control. He continued to work as an actor in dozens of films across multiple genres over the next several decades, in movies like Draft Day, The Guardian, Thirteen Days and Swing Vote. He even occasionally directed again — on much smaller-budget projects like the 2003 Western Open Range, in which he co-starred alongside Robert Duvall.

Still, what Costner couldn’t shake was a reputation for being difficult. He reportedly clashed with Clint Eastwood over creative differences on the set of the 1993 crime thriller A Perfect World, which Eastwood directed. He also reportedly clashed with Kurt Russell on the set of 3000 Miles to Graceland — yet again over creative differences. Even his friends would sometimes fall under his ire, including his longtime producing partner Jim Wilson, who’s credited on eight of his films, including Wyatt Earp, The Bodyguard, Message in a Bottle and Dances With Wolves. Costner sued him in L.A. Superior Court for $15 million in 2021 over a dispute involving Good Ones Production, the company he and Wilson formed in the 1990s.

“The word difficult gets used a lot,” says Rick Nicita, who represented Costner from 2002 to 2008 before Nicita retired from agenting as a partner at CAA (in the 1990s Costner was represented by Mike Ovitz). “It can mean someone who won’t come out of their trailer, or someone who doesn’t know their lines, or is rude. That’s not Kevin. He wanted what he wanted and knew what he wanted and if he didn’t get it … well, he was never a great compromiser. It’s a firm belief in himself and a confidence that to some can play as arrogance.”

Costner has never been an industry schmoozer. He’s lived mostly in a bluff-top oceanfront compound in Santa Barbara and at his 160-acre ranch in Aspen — by himself, since his divorce from second wife Christine Baumgartner (with whom he has three children; he has four others with two previous partners). Although he’s said to be something of a loner, he is known to be an adventuresome voyager, traveling the globe to dive for shipwrecks. He’s also a country music fan, with his own band, Kevin Costner & Modern West, made up mostly of session musicians he’s assembled over the years.

He’s said to take his counsel from a small, close-knit circle, including businessman Rod Lake, who’s dabbled in film production and still has faith in Costner’s vision (“He is certainly focused on finishing what he started with the Horizon series,” he tells THR). But his primary current consigliere is Howard Kaplan, a former Price Waterhouse accountant he met in 2009, around when Costner was making The Company Men with Ben Affleck, and who would resurface in Costner’s life years later — and who some of Costner’s friends believe wields a powerful influence over Costner’s professional life. But more about him later.

In 2010, Costner left CAA and signed with WME, where he’s currently represented, but Nicita has stayed in touch with him over the years. “Nothing that’s happened surprises me because Kevin firmly believes in himself,” he goes on. “He thinks he can will things into happening because he could, and he did. I don’t think that’s changed. What happened is the circumstances no longer allow for that. I’ve never known him to play the angles — it’s all fast balls down the middle. It’s just that the strike zone has gotten smaller. But I would never write him off.”

Indeed, shortly after the 2016 historical drama Hidden Figures — in which Costner played neither a cowboy nor a water-faring mutant but a NASA scientist — the actor landed that rarest of opportunities in Hollywood, a shot at redemption.

Of course, at the time, nobody knew what a phenomenon Yellowstone would become. But when it was announced that Costner had signed on to play the role of John Dutton, it set the stage for his return to superstardom, on an epic Western no less. (Sheridan had originally envisioned Robert Redford for the role, but when the show jumped from HBO to Paramount, the role went to Costner.) The pairing of Costner with Sheridan — who was 15 years younger — was immediately intriguing.

Sheridan had burst on the scene with Sicario, a gritty crime thriller about drug cartels set on the U.S.-Mexico border, which was followed up by the well-received Western crime drama Hell or High Water. It’s not hard to see parallels between Sheridan and Costner. Both started out as actors before finding their ways toward writing, directing and producing (in Sheridan’s case, that was out of necessity, as he never found success as an actor). Both are ruggedly handsome, gruff and not short on ego. Most of all, both have a deep and abiding affinity for frontier life and Westerns.

The first season of Yellowstone went smoothly enough. Other than Costner, the show was largely populated with relatively unknown actors — Costner was clearly the big fish in this smallish pond. But the extraordinary success of the first two seasons shifted the power dynamics on the set in Sheridan’s favor. The cast, most of whom owed their newly buzzing careers to the showrunner, were extremely loyal to Sheridan and 101 Studios, while Paramount executives were desperate to have Sheridan’s content for Paramount+, their new streaming app. As the seasons wore on, Costner became an increasingly polarizing figure, and certain castmembers were growing fed up with what several sources described as Costner’s “diva-like” imperiousness.

“The incident with Wes was the line in the sand. Everything was different after that,” says another source who was also present for the fight with Bentley. “Everyone loved Wes and so that really made Taylor upset. Kevin and Taylor butted heads from there on out. It got very awkward.” (A spokesperson for Bentley confirmed the altercation, calling it a “work related argument during an emotional and physically tough scene,” which was “discussed and resolved.” Costner’s spokesperson declined to comment on the near fisticuffs.)

Others say things got awkward when 1883, a Yellowstone spinoff that tells the origin story of the Dutton family, was announced and went into production. Around the same time, Costner had been circulating the script for the first installment for his own ambitious Horizon vision, a project he had been pitching around town since way back in 1988. This was Costner’s white whale, a $200 million Western that made Dances With Wolves look like a Sundance indie. Costner’s epic would be not one, not two, but four films set in the post-Civil War American West, spanning a 12-year period.

The problem was that no one wanted it. “Nobody was jumping to buy [Costner’s] odyssey and after 1883, he wanted to prove everyone wrong,” says a source. “He was obsessively pursuing it and as a result his world on Yellowstone starts unravelling.”

Dueling allegations started making their way into the press. It was reported that Costner, who had scrounged up some seed financing to start making his Horizon films, wanted to spend no more than a week on the Yellowstone set for the final episodes. Costner’s camp disputes that claim, alleging instead that Sheridan was the problem because he was late delivering scripts. Regardless, it would all soon come to an end. According to a source, Costner presented Paramount and the show’s producers with a list of demands required for his return to season five, including a $10 million upfront payment and script approval. Those conditions were rejected, and it was agreed that John Dutton’s character would be killed off in the first episode of the second half of season five.

At his peak, Costner was being paid around $1.5 million an episode, with a potential seasonal payday of over $10 million. Yellowstone was originally envisioned to run for six seasons, but a source on the show says, based on its success, it could have potentially stretched to eight seasons, meaning Costner might have pocketed something like $45 million if he’d continued playing John Dutton III.

Several sources believe that Kaplan, the former Price Waterhouse accountant, who by now had become Costner’s business partner and at times, his attorney (he represented Costner in that lawsuit against his former business partner Jim Wilson) played a part in Costner’s decision to leave Yellowstone and pursue Horizon instead. Kaplan flatly denies that assertion: “Whoever said that is either not in a position to know or is misrepresenting the facts,” he tells THR in an email, denying he has any undue influence over Costner. “Anyone who knows Kevin at all knows that he is his own man who makes his own decisions.”

In any case, Kaplan acknowledges that he was the one in Costner’s orbit most responsible for overseeing Horizon’s finances — and, sources say, he was the one Costner trusted the most.

“Howard made enemies out of everyone,” says Marc Weinstein, who was hired as the unit production manager for Horizon: An American Saga in February of 2022. Weinstein spent weeks scouting locations with Costner and was tasked with reviewing the budget for the first installment. After reading the script, he was floored when he learned that Kaplan and Costner thought they could make the film for $70 million. Weinstein thought it would cost closer to $130 million.

“I love Kevin Costner,” he tells THR. “But it got to a point where Howard alienated anyone who tried to get close to Kevin for the good of the project, including myself.” Kaplan fired Weinstein on Father’s Day in 2022. “The problem is no one knew what was going on with the money, not even Kevin. Kevin let Howard do anything. He let him make decisions, but he wasn’t informed. [Costner] never realized what all of this was going to cost him. It breaks my heart.”

Kaplan shoots back: “Marc Weinstein was terminated based on his performance more than eight weeks before the start of photography on Horizon,” he says. “Mr. Weinstein was not one of Kevin’s representatives and he would have absolutely no knowledge of what Kevin was or wasn’t aware of.”

Of course, even without Costner, Yellowstone would ultimately become a billion-dollar asset for Paramount, spawning seven different spinoffs. Sheridan, who declined to comment for this story, is now one of the most bankable names in town, with Paramount Skydance CEO David Ellison recently calling him a “singular genius with a perfect track record.”

Still, there’s clearly some lingering bad blood between the two old cowboys. According to one well-placed source, Costner had a hard time finding horses and cows to rent during his Horizon shoot in Utah. The rumor on the set was that most of the livestock had already been rented … by Taylor Sheridan.

***

When people close to Costner read the original script for Horizon, which clocked in at well over 180 pages, many urged him to drastically cut it and revise it. The script includes a sprawling cast of characters with disparate story lines that all converge on a fictional Western settlement. “I couldn’t get through it. It was bananas-ville,” says a source who read an early draft.

Costner, who declined to comment for this story, admitted as much in a 2024 GQ magazine profile: “If my psychiatrist looked at me and they said, ‘Kevin, let me get this straight. Nobody wanted to make one, right? At least at that point when you stopped, they didn’t want to make it?’ I said, ‘Yeah.’ And she goes, ‘Why do you then go out and write four more? Why do you go and do that?’ And I guess the answer is: Because I believe.”

Securing the necessary financing was an uphill battle, but Costner had done this before on Dances With Wolves, and that is what he repeatedly brought up in pitch meetings with investors. He was able to secure an early key ally, Danny Peykoff, heir to a bottled water fortune, who put in a low-eight-figure investment and use of his private jet. He found other investors: Tanner Beard of Silver Sail Entertainment, and even a few million in grant money from the state of Utah, where he promised to shoot the four films. Foreign presales, which he secured at Cannes in 2023, would provide a financial backstop, and as he did with Wolves, Costner put some of his own skin into the game, this time a whopping $38 million.

At the time, he had the money — or at least the collateral. Costner owns several trophy properties, including a 10-acre empty oceanfront parcel in Carpinteria, which was once listed for $60 million. Like a gambler in an old timey saloon, Costner dropped keys to that estate into the poker pot that was becoming Horizon’s financing.

By spring of 2022, he had pulled together enough money — and assembled a cast including Luke Wilson and Sienna Miller — to start shooting the first and second of the four films. That’s around when Warner Bros. signed on as the film’s domestic distributor.

In the spring of 2024, shortly after production wrapped, Costner took the first Horizon movie to the Cannes Film Festival. There were, sources say, concerns the movie wasn’t ready for exhibition and needed more time for testing. But Costner, true to form, took the film — and some of its cast — to France anyway, screening it out of competition, where it failed to wow many critics (at the time, Rotten Tomatoes gave it only a 27 percent rating based on the early reviews). It did, however, receive a 10-minute standing ovation, which reportedly brought Costner to tears.

A month later, on June 28, 2024, Horizon: An American Saga — Chapter 1 was released in theaters and pulled in just $11 million during its opening domestic weekend, a box office disaster nearly as horrific as Waterworld and Heaven’s Gate. It ultimately grossed just $38.7 million on a $100 million budget — although, as Costner’s spokesperson points out, it was HBO’s top film on the platform when it streamed in August 2024. The second installment, Horizon 2, was supposed to be released just a few months after the first, but WB pulled it after the first film’s disappointing results. There’s currently no release date.

***

“I need some more money — I do. I need some of these big billionaires, with fucking boats ‘from here to here’ who are fond of telling people they’re billionaires, to come with me and make a movie,” Costner told THR one year ago in Cannes. “I don’t have the money they have, and I’ve already made two of ’em. Where are you rich guys?”

Last year, Costner made a trek to Riyadh looking for those rich guys — and to accept a lifetime achievement award at Saudi Arabia’s Joy Awards. “Saudi Arabia deserves its place on the world stage, and I urge you to tell your own stories,” he said during his acceptance speech. “Invest in the emotional, and the universal and the historical that you know them to be — you will never regret it.”

While in Riyadh Costner met with top Saudi officials and pitched them to help finance the third and fourth installments of Horizon. According to two sources, the Saudis were open to investing a certain amount in the franchise, but not the sum that Costner was seeking. He ultimately walked away with nothing. Costner’s spokesman confirmed but downplayed those talks saying that he had “cursory” discussions with Saudi officials about financing Horizon.

Since then, he’s been dealing with the fallout from the Horizon disaster, like a lien on that vacant $60 million Carpinteria property he leveraged for financing. In March, a discovery hearing is scheduled for arbitration pitting Costner’s company against Horizon’s bondholder, City National Bank, and its distributor, New Line Cinema, both of which have financial disputes over the film (as COO of Costner’s production company, Kaplan will almost certainly play a central role in that hearing).

In just a few weeks, he’ll be in L.A. Superior Court for a pretrial hearing regarding a female stunt performer who in June filed a suit against Costner alleging that she was forced to perform an unscripted rape scene without proper safety protocols. (Costner has called the claim a “bald-faced lie.”) And there may be other conflicts looming — investor Tanner Beard, who put in $3 million in the form of a bridge loan, tells THR in a statement that his “attorneys are reviewing what has transpired here in order to advise on the best course of action.”

Costner has a few projects in the pipeline but hasn’t acted onscreen since Horizon. It was recently announced that he’ll co-star in a dramedy with Jake Gyllenhaal for Amazon MGM and he’s attached to a surf thriller called Headhunters (Disclosure: the writer of this story was once developing a television series with one of the Headhunters’ producers based on an article he wrote in 2021. That project is no longer active). Where he has been busy is on the celebrity speaker circuit. This year alone, he gave paid speeches at the International Dairy Deli Bakery Association; Impact Bucharest, which is a conference for entrepreneurs; and a keynote address at VMX 2025, the world’s largest veterinary conference. (“Kevin’s always done speaking engagements,” notes his spokesperson.) He’s also discussed starting his own rum brand, à la George Clooney’s Casamigos tequila.

But despite the legal headaches, the continuing costs and the reputational harm the Horizon debacle has caused him, he has shown no indication that he plans to cut and run from his vision of producing four epic Western films. He continues to pound the pavement looking for financing to finish the third and fourth installment.

Indeed, there was a flurry of news stories earlier this year that construction was underway on a $100 million film studio in St. George, Utah, that Costner and his Territory Pictures were spearheading with a local developer named Brett Burgess. The project includes a 39,000-square-foot multipurpose warehouse and a 20,000-square-foot soundstage with an additional 10,000 square feet of office space.

“He sees a future here for filming,” says Joyce Kelly, who heads up the film commission in Greater Zion, Utah. “I’m confident that they will release Horizon 2 and that three and four will get done. I saw Horizon 2 and I thought it was amazing. We’ve invested in this and I’m rooting for him.”

Costner’s spokesperson insists the project is indeed moving forward and Burgess, the other developer building the studio, didn’t respond to THR’s inquiries. But another source who works closely with Burgess and who has recently driven by the site had a very different take. “It was guns a blazing,” he says of the initial plan for the studio. “They built a first structure that’s about 80 percent complete. But right now, there’s really nothing happening. After Costner’s movie didn’t do so good, things changed, and Kevin’s been unavailable ever since. Could it still happen?” he ponders. “Possibly.”

Possibly, indeed. Like an old Western gunslinger, Costner has been counted out before — only to gallop back onto the screen, battered and bruised, riding toward the next horizon.