The first Jewish basketball player to make the NBA All Star-Game was Dolph Schayes, in 1951. Schayes would go on to make the next eleven, his two-handed arcing jump shot and lightning-quick drives to the basket turning the 6′ 8″ forward into a superstar.

The most recent Jewish basketball player to make the NBA all-star game was Deni Avdija, an Israeli playing for the Portland Trailblazers who stands exactly as tall as Schayes did and drives just as fast. Avdija is having a breakout season, averaging 25 points, seven rebounds and seven assists per game, numbers that helped land him the fifth-most All-Star fan votes in 2026, ahead of Victor Wembanyama and Kevin Durant.

Avdija is no anomaly, at least not historically. Jews have deep roots in basketball, dominating the game in pre-War America, especially at the college level; one famous contest between undefeateds NYU and City College of New York in 1934 featured nine of ten Jewish starters and landed the nascent sport in Newsweek and The New York Times. As recent immigrants, Jews played the game in their dense urban neighborhoods and helped popularize it with traveling teams up and down the East Coast. That changed with migrations to the suburbs and as the game developed in new directions. But basketball has always been tied up with the Jewish-American experience.

Needless to say, then, Avdija’s appearance on the NBC telecast Sunday night — he notched five points and two assists in eight minutes for the World squad and caught the attention of LeBron James — was a source of pride for many Jews, who continue to play basketball in schools and recreationally perhaps more than any other sport. Among Jewish Americans this basketball season Avdija’s performance has been a talking point everywhere from rec-league pickup games to family WhatApp groups. “Can you believe what he threw down last night?”

It’s unlikely Spike Lee knew all of that, though as a student of basketball, it’s fair to assume he caught some of it. But he does know a thing or two about ethnic pride and identity, having made countless movies about the topic. And if none of that clocks, his longtime production office is a few blocks from the Barclays Center, home of the Brooklyn Nets, where two Israeli-backgrounded Jews, Danny Wolf and Ben Saraf, currently play.

Which is why when he showed up courtside at the Intuit Dome Sunday night wearing a keffiyeh-patterned hoodie, a shoulder bag with the colors of the Palestinian flag and what appeared to be the infamous upside-down red triangle used by Hamas to identify the presence of Israeli soldiers, all seemingly to be in the eyeline of both Avdija and the millions of Jews watching him, it felt like an affront.

Lee didn’t say anything in a quick red-carpet walk in to the arena, and if you asked him, he might say he wasn’t aiming it at Avdija and was just making a general political point. But he would be playing a fancy-footwork game worthy of Luka Dončić. The director gets to show up at the game and have the effect of provoking the Jewish player running up and down the court in front of him, even as he retains the ability to say he just happened to feel the need to get political that night.

Supporting the Palestinian cause is Lee’s right, of course, but no Palestinian was playing in the NBA All-Star Game. Protesting the Israeli government’s actions in Gaza or anywhere else is also very much Lee’s right, but no Israeli government officials or even national team was playing. The man who was playing was guilty of little more than being born in Israel, and for that he apparently deserved an ongoing in-game protest. Even the small Israel flag embossed on Avdija’s jersey was no different from the flag worn by any other of the international stars, including Nikola Jokić, who grew up in Slobodan Milošević’s Serbia, and Alperen Sengun, who was raised in Recep Erdoğan’s Turkey, and had those flags on their jerseys. If Lee wore an article of clothing protesting their involvement in the game, I somehow missed it.

A very different scene has been playing out for Jewish and Israeli athletes halfway around the world. In a record showing, Israel sent nine athletes to the Winter Olympics across five disciplines this year, up from six athletes at the Beijing Games. The country has exactly one mountain that regularly gets snow, but it has become a source for one of the feelgood stories of the Games courtesy of the Israeli bobsled team — led by AJ Edelman, brother of Alex Edelman, the Emmy-winning writer and performer of the HBO special and Broadway hit Just For Us.

AJ Edelman had taught himself how to skeleton and competed for Israel at the 2018 Games in Pyeongchang; now he had pivoted to another sport and made the Olympics again. He and his two-man-bob teammate Menachem Chen stood at 26th out of 26 sleds halfway through the competition (where they would finish) but were still pumping their fists after their runs like they’d landed on the podium. As an NBC news story noted, “AJ Edelman and Menachem Chen are in last place out of 26 sleds at the midway point of the Olympic two-man bobsled race at the Milan Cortina Games. And they’re thrilled.”

There has been very little visible Spike-like protests of the Israeli athletes. A commentator for the Swiss broadcaster RTS did say on-air that, because Edelman was pro-Israel, “one can therefore question his presence in Cortina during these Games,” but RTS had the good sense to take the comments down, even if they didn’t exactly denounce them.

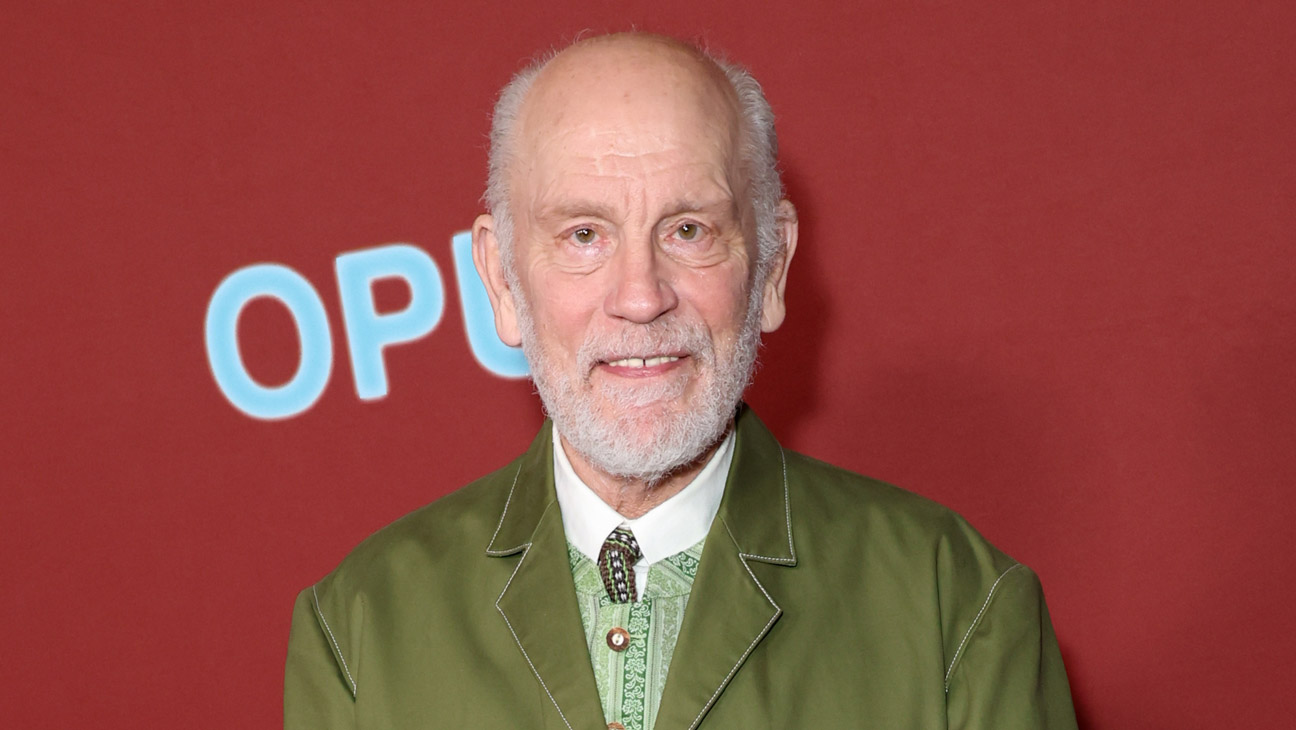

And then there’s Marty Supreme, which has been beaconing Jewish pride since Christmas Day, its title character competing not just with the Jewish stereotype of smarts but with stamina and skill, a ferocious athleticism. The scene has been striking: A Jewish actor playing a Jewish sports legend to millions of non-Jews who don’t bat an eye.

Jews excited about Jews in sports is a strange and, yes, sometimes funny beast. On one hand, the enthusiasm almost undermines its own point; if such an event were actually common it wouldn’t be celebrated with such gusto. (See under: the classic Airplane! bit “how about this leaflet, famous Jewish sports legends?”) On the other hand, for many Jews a genuinely deep, almost existential thrill comes from such a sight.

Partly that’s because any of us intramural or beer-league legends want to imagine that, but for a twist of fate, it could be us winning gold or draining the Game 7 winner, and how much more realistic if the athlete who does sits down at the same seder table. But it of course goes deeper than that, to the same issues of representation that echo through much of Hollywood — of seeing someone who looks like you excelling at something you’ve rarely seen them excel at, then taking that improbable inspiration into your own life on a smaller stage.

That’s why Edelman and Chen’s bobsled runs have been so miraculous. Ice and snow sports? Where you jet down a mountain at death-tempting F1 speeds? That requires a WASPish pedigree, not to mention a Jewish mother who has been medically induced into a coma. We never see Jews doing that. And yet here some were, under Olympic lights. When Alex Edelman took a good-natured dig at his brother in Just For Us at how good AJ was at a sport that only about 50 people in the world competed in, it got a laugh for the enjoyable snark but also a little nod of pride that AJ was doing something so rare in the first place. (Just for Us has been leaning in to the younger Edelman’s Italy competitions on social.)

But the sight of a Jew excelling in sports is even more than a bit of representational inspiration. So much of antisemitism, historic and resurgent, is bound up with demeaning Jews as genetically inferior — at the top line with Hitler and those infamous Olympics 90 years ago but also much more casually, in easy jokes and schoolyard assumptions, in the implication that genetic makeup makes Jews less athletic. (Funny how some of the same people trading in these stereotypes also paint Jewish soldiers as fierce goons; who says hate has to be consistent?) And so the sight of Jewish-Americans Aerin Frankel, the goalie on the unstoppable U.S women’s hockey team, pitching three shutouts and counting, or dominant speed skater Emery Lehman, who just won silver in the men’s team pursuit on Tuesday, resoundingly shuts down the argument. The U.S. men’s hockey team is anchored by the wizardry of star forward Jack Hughes and his brother Quinn Hughes back on the blue line. Both are Jewish, the sons of women’s hockey pioneer Ellen Weinberg.

Even the greatest slalom skier of all time, Mikaela Shiffrin who, OK, she’s a little harder to claim, but would’ve been Jewish enough to pass the old Nazi test.

And, of course, the Israeli bobsled team, aka “shul runnings.” The pun is great. The story is even better.

Taking in all these great sights on so many screens has the effect of marginalizing a Spike Lee and his apparent belief that a Jewish athlete exists only as a vessel for his virtue-signal fashions; the director deserves no more emotional energy than a whatever eye-roll for his performative narcissism. Lee can’t kill the mood of anyone excited about Jewish sports swagger. He can just remind us why it’s needed.