[This story contains major spoilers from No Other Choice.]

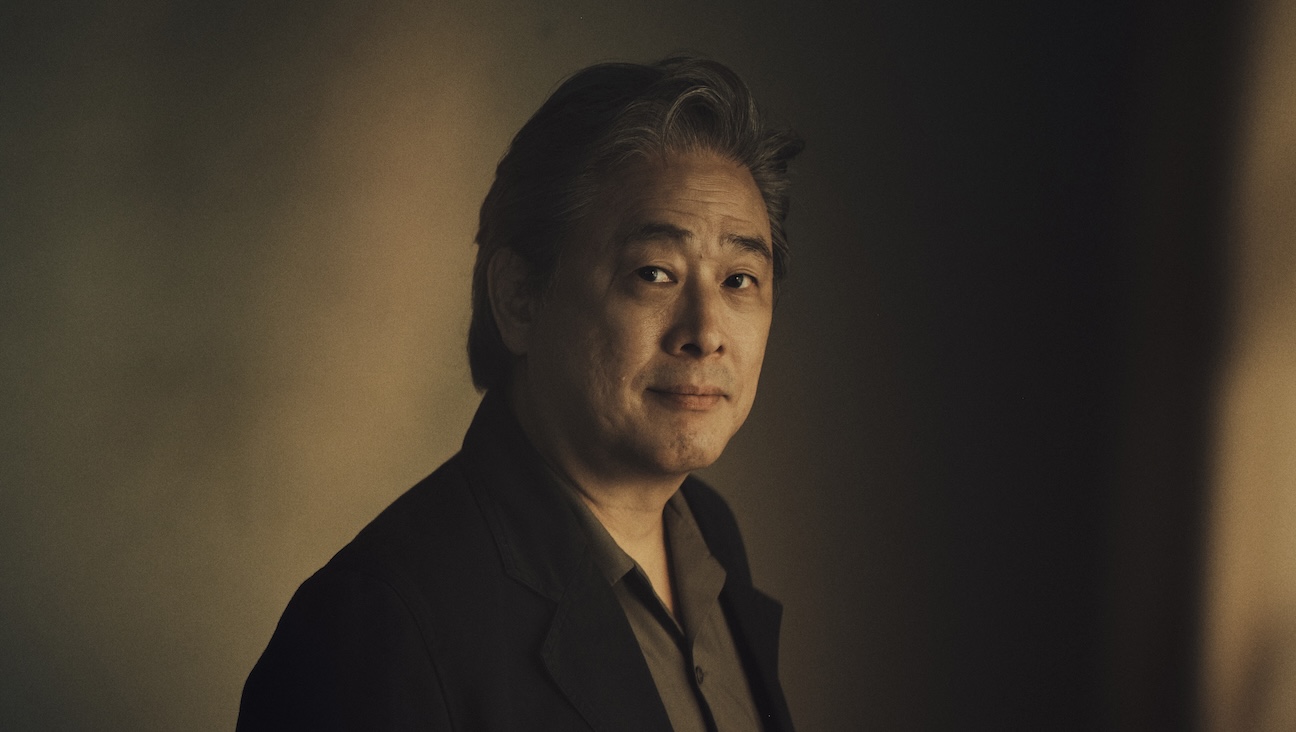

The great Korean auteur Park Chan-wook has produced several undisputed masterpieces over his three-decade career, but none so urgently of-the-moment as No Other Choice, his latest black comedy thriller.

A passion project more than 20 years in the making, No Other Choice is adapted from Donald Westlake’s 1997 novel The Ax. During its long gestation, the film was at one point set up at Netflix as an English-language thriller, before a tangle of development complications brought it home as a Korean feature starring two of the country’s most beloved screen icons: Squid Game star and perennial leading man Lee Byung-hun, and national sweetheart Son Ye-jin.

Park says he held onto No Other Choice through decades of development hell because he always believed its premise — absurd, tragic and painfully universal — had the potential to become a “defining work” within his filmography.

“Whenever I told people about the story, no matter the time period or country they came from, they would always say how relatable it was,” he recalls. Despite that, the year 2025 might just be the perfect moment for No Other Choice to meet a suitably anxious and economically pressed worldwide moviegoing public.

A jet-black social satire, No Other Choice follows Yoo Man-su (Lee Byung-hun), a devoted husband and father sent into an existential tailspin after he’s laid off from the paper mill where he’s toiled for decades. Threatened with obsolescence as the only industry he knows lurches toward AI-powered automation, Man-su moves through a series of humiliating interviews and rejections in a job market with too many applicants and too few openings. His loving, pragmatic wife, Mi-ri (Son Ye-jin), gamely downsizes their middle-class life to fit their new reality — but her resoluteness only exacerbates his despair. Soon, Man-su, twisted by self-pity, convinces himself that his “only choice” is to tip the job market back in his favor — by eliminating his rivals one by one.

But Man-su is no slickly skilled killer, and nor should he be. Deploying his full arsenal of baroque visual inventiveness, Park highlights the tragicomic absurdity of this lost family man’s mission by infusing his death drive with Looney Tunes-like physical comedy. The result is Park’s most mordantly funny film in years — a work of furious timeliness that skewers the indignities of modern labor, the fragility of masculine pride, and the absurd moral contortions we all perform to preserve a scrap of dignity inside the late-capitalist, AI-encroached machine, where self-respect feels inseparable from self-delusion, and anything resembling class solidarity doesn’t even occur as a viable afterthought.

Beneath the film’s slapstick hysteria lies what the director describes as “the bitter capitalist reality” — “the capitalist system’s nature of making ordinary folks point knives at each other.”

No Other Choice released its first U.S. trailer on Thursday, the day before its North American premiere at the New York Film Festival. Specialty hitmaker Neon will release the film nationwide on Christmas Day and is expected to mount a major awards-season push.

Park, who has, incredibly, never received major awards recognition — despite a filmography that includes virtuoso works like Joint Security Area, Oldboy, The Handmaiden and Decision to Leave — will wear his usual gentlemanly good cheer throughout the campaign regardless. But expect more than a few awards pundits to declaim that the Academy, finally, has no other choice but to present Park Chan-wook with his first Oscar nomination.

The Hollywood Reporter recently sat down with Park to discuss a few aspects of No Other Choice‘s creation.

So I understand it took you over 20 years to bring this adaptation to the screen. What was it about the original story and its themes that captivated you for all these years?

When I read the book about two decades ago, I immediately knew I wanted to adapt it into a film. It’s a story that deals with the urgent inner world of an individual as well as the big societal issues that surround him. Adapting it would allow me to explore both of these dimensions in a totally seamless way — and that’s the kind of cinematic subject matter directors are always looking for.

I instantly had ideas for things I was excited to change or add in the adaptation process, too. The tragedy of the book was very compelling to me, but I felt there was potential for black comedy, which could make for a very fun movie. I also had the idea of adding a layer — that the protagonist’s wife and son would end up gaining some understanding of the terrible things he has done. Often, when people tell themselves, “I’m doing it for my family,” the very thing they are doing — or the pursuit of it — is what actually ends up damaging or dismantling their family. What a pitiful paradox. As soon as I had this thought, I never wanted to let go of the project.

Now I can’t resist jumping to the ending… When you say Man-su’s family ends up dismantled, do you mean because they are all morally compromised in the end? Or because Man-su has passed on his generational trauma? I ask because I think some viewers might finish the film thinking that Man-su actually got everything he wanted.

This uncertainty is exactly what I aimed for, and this question is what intrigued me. As the audience leaves the theater, how will they interpret the future of this family? For example, one of Man-su’s biggest motivators throughout the story is to avoid being forced into selling the family home. And toward the end, Mi-ri, his wife, finally says, “We’re not going to sell the house.” But she adds, “We can’t — we just planted that apple tree!” There are two ways of interpreting this. She could be saying, essentially, “We’ve built and nurtured this home together. We’ve done so much together, we can’t let that go.” Or she could be hinting that she knows there’s a dead body buried under that apple tree. In that case, she’s saying, “If we sell the house, the new owners might accidentally dig up a corpse. We can never let that happen, which means we can never leave. I know the things you’ve done, and we’ll never go back to the way things were.” There are similar hints and ambiguities about what the children know and how it has affected them.

Although the satire is pitch black, this film is a lot more overtly comedic than most of your films.

I would say that I always work with the same ingredients; I’ve just mixed them up differently for this recipe. I’ve always liked having dark humor in my stories, but with this film, the humor stands out much more. That was very important from the beginning. The book isn’t in-your-face comedic, but I thought that by exaggerating Man-su’s foolishness, I could deepen the message. I wanted to really highlight the tragic absurdity of his ideas and how he puts them into action.

As he says in the film, the gun should be pointed at the enemy, not at your friend. You have to take on the system. The solution to our problems can only be found by fighting the system. But very foolishly, before long, he’s targeting his fellow colleagues — the poor laborers who are in the same precarious position he is in. This leads him to commit terribly immoral acts, all the while telling himself he has no other choice — that he’s doing it all for his family. And the result, as we’ve discussed, is that he only degrades himself and his family in the process. So, it’s very likely that everything he has done is in vain. It’s tragic, but there’s also such absurdity to it.

Hitchcock is the filmmaker most often cited as a formative influence on you, and you’ve spoken about the profound impact of seeing classic American films as a kid via U.S. military broadcasts in Korea in the 1970s. This film, though, made me wonder whether vintage American cartoons might also have shaped you — because Man-su’s actions are explicitly Looney Tunes–like at times. There are a number of comedic moments that seem to reference classic cartoons, such as when he pulls multiple layers of gloves off his gun before shooting. Thinking back on your filmography — even some of the wildest moments of Oldboy — it suddenly feels like there are traces of this influence everywhere in your visual language.

That’s very accurate! And you’re right, people tend to point to the highbrow influences (laughs). But I used to watch loads of cartoons on TV growing up, and I’ve always been a huge fan of the kind of incongruent visual humor you find in those old animations. Animation certainly influenced me.

There are so many set pieces in the film that are almost overwhelmingly rich in their visual detail. Like Decision to Leave, it’s all immensely enjoyable on the first watch, but the film occasionally outpaces the viewer’s ability to process all of the visual information you’re deploying, basically requiring multiple viewings. So let’s zero in on one scene: the sequence where Man-su confronts his first victim at gunpoint in his living room. It’s a classic showdown sequence we’ve seen in so many action thrillers before, where the characters are going to confront one another face-to-face with a gun drawn. But you’ve found a completely original, hilariously expressive way to do it. The victim is an audiophile, and he happens to have the classic Korean rock song “Red Dragonfly” by Cho Yong-pil blasting on his living-room stereo throughout the confrontation. The song is playing so loudly that the characters can barely hear each other as they shout, but the song itself seems to be expressing — gloriously — all of the deeper nostalgic lamentation these two men actually share at this late stage in their lives. How did you conceive of this sequence?

So much can be said about this scene. As you mentioned, Man-su shows up wearing multiple gloves over his right hand. These are actually oven mitts, which we’ve shown earlier in the background of his family’s kitchen. He’s worn them to muffle the sound of his gun, but the music is so loud he realizes he doesn’t need them, so he dramatically removes them one by one. Underneath, we then see that he’s literally tied the gun to his hand with some vinyl cords — this shows his resolution and determination, that he will, no matter what happens, not drop the gun. He will be connected, almost fused, to the gun and become one with it. Of course, all of this also reveals what a clumsy, ridiculous killer he is. This isn’t a professional assassin.

And then he shouts those great lines. As we’ve seen, Man-su’s been observing his target, Beom-mo, for some time — and they have a lot in common besides both being laid-off paper-mill workers. They both have a hobby that’s also a passion. Man-su locks himself in his greenhouse all the time, working on bonsai trees and plants for his garden. Beom-mo is really into audio and vinyl records. So I wanted to utilize that commonality.

The idea being that these men do have “other choices”?

Right. So Man-su has been observing Beom-mo’s life carefully, and he’s frustrated by what he’s seen. So he shouts, “You won’t even listen to your wife’s reasonable suggestions! What’s wrong with opening a vinyl café as she told you?!” Of course, these are all the things he should be saying to himself. We’re revealing that some part of him knows this about his own situation, but he rejects it. He could just sell his house and move the family into something more modest, and possibly pursue gardening, which he loves — this would be so much better than killing people so that he can stay in the paper industry. But he rejects it. Beom-mo is an opportunity to yell at himself, in a sense. It’s almost as if he’s shouting into a mirror.

Of course, there’s a third party in the melee too — Beom-mo’s wife, who has been having an affair. Beom-mo assumes Man-su is his wife’s lover, so when Man-su attacks him and begins shouting these things, he doesn’t question why he knows this stuff about his life. Instead, he cries out, “She even tells you these things?!” — like, “I understand she’s having an affair, but she tells you about our personal life too?” That’s deeply hurtful to him — and Man-su actually feels bad for him in that moment, even as he’s attempting to kill him, and that’s another funny beat. Meanwhile, Beom-mo’s wife enters the scene. She tries to protect her husband by attacking Man-su, but at the same time, she agrees with the things he’s been shouting at Beom-mo, so she’s also screaming at her husband and attacking him with her words. So we have this ridiculous circular chaos. The funniest part to me is that amid this violence — as someone is literally trying to kill him — the thing that enrages Beom-mo the most is when his wife’s top starts to slip down. He’s about to be murdered, but the thing that makes him let out the most pitiful scream is the fact that his wife’s skin is showing.

Going back to Joint Security Area, your films have always had elements of social resonance — especially at home in South Korea — but you’ve arguably never addressed the concerns of the moment as directly as you have with this film. So, final question: Do you really believe that we have another choice — that there’s a viable way for ordinary people today to resist technological determinism and the capitalist meat grinder?

(Heavy sigh) Well, looking around at the state of things, we are definitely in a position where it’s hard to be optimistic. But I lack the courage, or the thick skin, to say it’s all over. The way technology is evolving and coming at us with such speed — and with the looming reality of climate change, which we’re not dealing with at all — I think we’re going to face crises that humanity has never experienced before. I am scared too. But it’s still too early for us to completely give up. Despite our many tragedies and mistakes, we have to believe that humankind has the potential to make progress.