There was a moment, back in 2012, when Diane Keaton and Robert Redford nearly shared the screen. Both were reported to be “eyeing” the leads in a holiday-themed ensemble comedy titled The Most Wonderful Time, pitched as a Love Actually-style pastiche involving multiple interwoven tales of family and romance, all set against a backdrop of Christmas lights and yuletide meltdowns.

Alas, that movie never got made — at least not in that form — and Keaton and Redford never again came so close to working together. But in their own ways, these two very different actors — she, the eccentric spirit of New Hollywood comedy; he, the golden-boy stoic of the American pastoral — were bound by something even more powerful than onscreen chemistry: generational gravity. They belonged to the same loose orbit of 1970s-era performers who upended the rules of stardom and helped reshape what American movies could be.

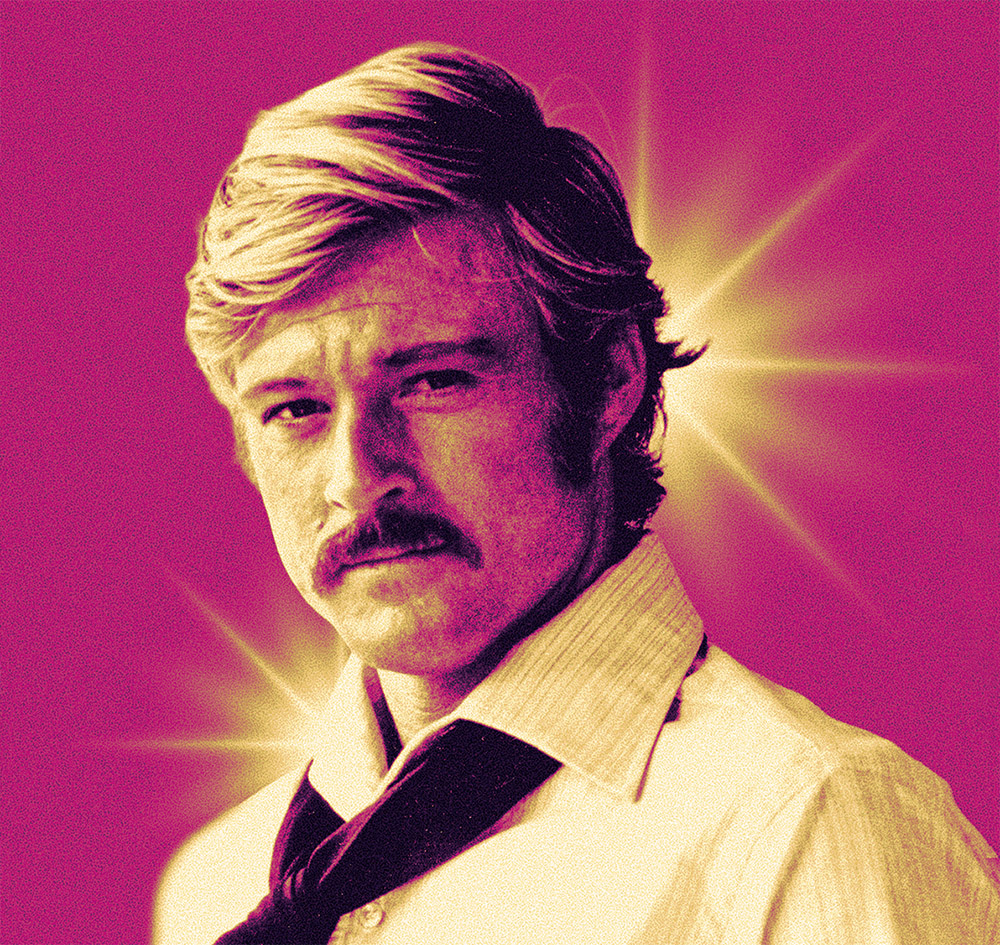

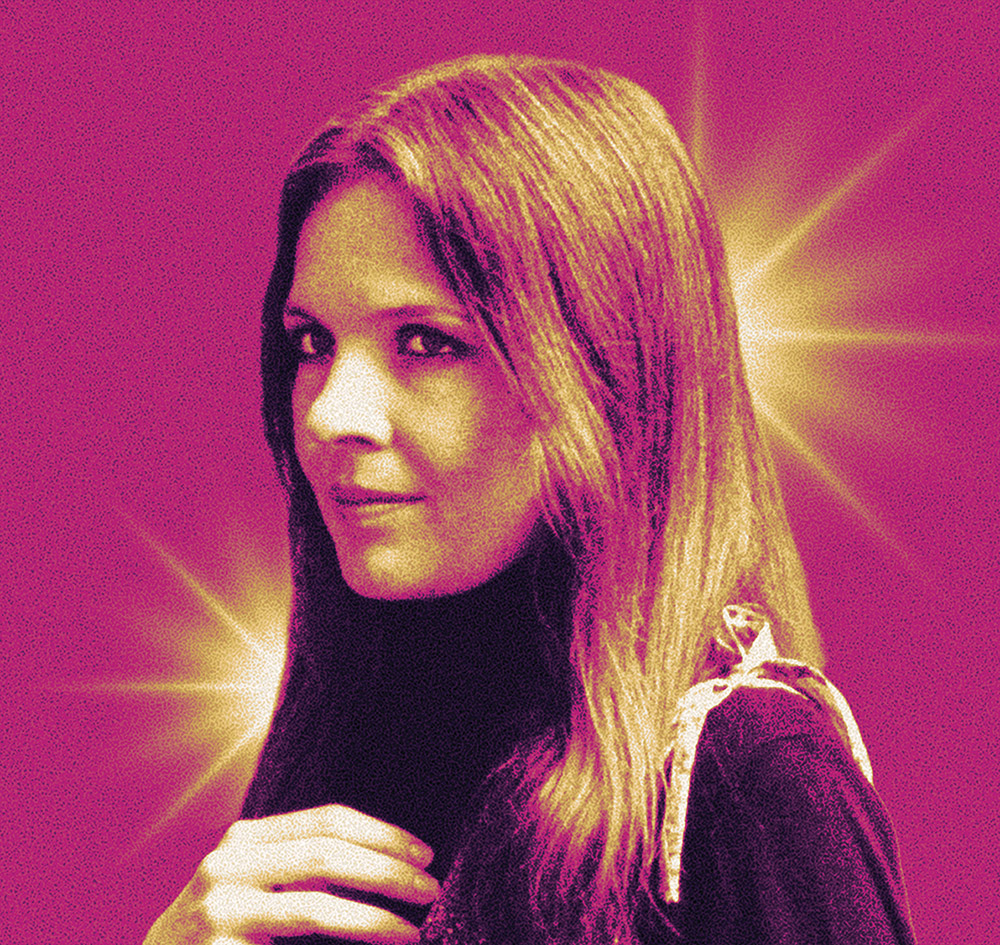

Keaton died Oct. 11 at age 79 after a shockingly quick battle with pneumonia. Redford died in his sleep, at 89, a little less than a month earlier, on Sept. 16. Some from their cohort had gone before — Paul Newman in 2008, Shelley Duvall in 2024, Gene Hackman in February — while others have simply drifted from view. Warren Beatty, Jack Nicholson, Dustin Hoffman, Faye Dunaway — all now in their 80s — have largely stepped away from the spotlight.

Of course, this is nothing new. All stars, even the brightest, eventually flicker out as new generations take their place. But there’s something different — something more poignant — about watching this particular circle begin to vanish.

The stars who came before them had been shaped by the studio system — groomed, styled and slotted into types. They signed long-term contracts, wore what the wardrobe department handed them and gave interviews ghostwritten by studio publicists. Even the greats — Bogart, Hepburn, Gable, Davis — were often playing variations of a persona the system had helped construct. Their power came from polish, execution and consistency. Stardom was a product, and it was carefully managed.

By the time Redford, Keaton, Beatty and the others were coming of age as actors, the old studio scaffolding was already coming apart, with the contract system unraveling and the great moguls who once ruled the town with an iron fist fading from the scene. There was no longer a press-office puppeteer telling actors how to dress or what to say, no studio image to protect. They were free to define themselves — onscreen and off — and to let those two identities blur. Their personas could be withholding, eccentric, neurotic, ambiguous, strange. They could play characters the previous generation never got near: complicated people with unresolved feelings and messy inner lives.

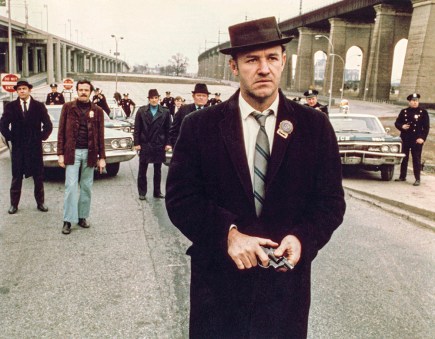

At the same time, a new kind of director had taken over the asylum — such mavericks as Mike Nichols, Robert Altman, Hal Ashby, Alan J. Pakula and Martin Scorsese — filmmakers who weren’t interested in preserving the system. They wanted to blow it up. Their films — Carnal Knowledge, McCabe & Mrs. Miller, Shampoo, Klute, Taxi Driver — didn’t just break the rules, they rewrote the language of cinema itself. And that reinvention gave this young, liberated generation of actors a canvas as unbound and unconventional as they were — a kind of free-spirited platform that hadn’t existed before and hasn’t really existed since.

Few actors made better use of that freedom than Redford and Keaton. In such films as The Candidate, Three Days of the Condor and The Way We Were, Redford turned the clean-cut leading man into something more introspective and morally uncertain — a figure torn between idealism and self-interest. Keaton took the same open, idiosyncratic presence that made Annie Hall so engaging and revealed its darker shades in The Godfather and Looking for Mr. Goodbar, proving she could be fearless, complex, even unsettling. Both found truth in contradiction. They made uncertainty look thrilling.

But by the early 1980s, as the counterculture spirit of the previous decade gave way to something more box office-driven and less tolerant of creative chaos, a different model of movie star started taking over. Actors weren’t seeking to challenge the system anymore; they were the system, powering tentpoles, sequels and high-concept hits that could sell in every corner of the world. This was the era of the Event Movie, when opening-weekend grosses became the new measure of stardom. The actors who began appearing on marquees — Schwarzenegger, Stallone, Willis, Gibson, Cruise — weren’t celebrated for subtlety or transformation or their onscreen bravery, but for their box office clout.

Sure, by the 1990s, there was a parallel indie movement where some of these stars could unfurl their dramatic range, ’70s-style — Cruise in Magnolia, Stallone in Cop Land — but for all the critical acclaim and Oscar attention those roles might attract, what defined success in 1980s and ’90s Hollywood were the ticket sales for such tentpoles as Top Gun, Die Hard, the Rambo movies and The Terminator. Actors had become commodities of scale, defined largely by their ability to summon $100 million grosses.

When the new millennium arrived, that equation shifted yet again, even if the focus on money hadn’t. Hollywood’s center of gravity moved from stars to franchises. The IP became the real draw — superheroes, wizards, Jedi and other branded worlds. The costume, often spandex, mattered more than the actor inside it (even Redford got in on the act, playing a Marvel villain in Captain America: The Winter Soldier). Stardom no longer was the engine of the movie business; it was just another interchangeable part of the business.

Then, in the 2010s and ’20s, stardom started moving from the big screen to a much smaller stage — the phone. Hollywood was still turning out superhero sagas, prestige dramas and cozy seasonal fare (like that Christmas movie, The Most Wonderful Time, eventually rewritten and released in 2015 as the forgettable Love the Coopers, with Keaton still starring and Redford’s role taken by, of all people, John Goodman). But the real competition for attention was moving elsewhere — to feeds and timelines, where fame was measured not by box office totals but by followers.

a horror film reinventened for the 1970s.Sunset Boulevard/Corbis/Getty Images

Stars used to vanish between films. Today, they’re required to stay perpetually present — posting skin care routines, political endorsements, personal podcasts. The carefully curated distance that once made icons feel larger-than-life has been replaced by the algorithmic closeness of TikTok confessionals. Even the indie-minded actors who might’ve inherited the Keaton/Redford mantle — your Ethan Hawkes, Michelle Williamses, Adam Drivers — have had to negotiate this attention economy. They’re still serious actors, but they exist in a culture that prizes access over aura. The art of elusiveness — that quality of unknowable magnetism — has almost vanished.

Every now and then, you catch a glimmer of that older magic — the awkward honesty and unvarnished humanity that defined the 1970s generation. Films like The Holdovers, Licorice Pizza, even Once Upon a Time in Hollywood evoke that mood again, though now it plays like nostalgia for the era when stars like Keaton and Redford ruled the screen. What was once rebellion now reads as retro — authenticity repackaged for an audience yearning for the very messiness that once made those earlier actors feel so real.

The irony, of course, is that this new generation has more tools than ever to control their image, yet less actual control over how they’re perceived. Every red carpet misstep, every viral sound bite, is instantly flattened into content. Stardom, once about transcendence, has become a form of relentless participation.

As for the next generation of stars — if there’s even to be one — it’s hard to imagine it resembling the actors who came before, least of all the unruly brood who took over the screen during the 1970s. The conditions that once created icons have splintered. Theaters are shrinking, audiences scattered, and the machinery that once turned actors into household names has gone digital. Stardom used to depend on scarcity; the future will run on replication.

When a Dutch creator recently introduced Tilly Norwood, a fully AI-generated “actress,” it wasn’t her performance that felt uncanny — it was the idea behind it. A star with no past, no flesh-and-blood body, no human connection at all. Just a simulation of emotion, programmed to deliver the illusion of depth. Ironically, it’s the exact inverse of what defined the 1970s generation: actors whose power came from being recognizably, sometimes painfully, real.

Stars like Keaton and Redford were messy, mercurial, alive — and that was the point. They and the other ’70s actors reminded audiences that being human was the story. Tilly, and the technologies that will follow her, promise something cleaner, faster, cheaper and more controllable — but infinitely less relatable. Maybe that’s progress. Or maybe it’s the final act in a long process of polishing the humanity out of movie stars altogether.

This story appeared in the Oct. 22 issue of The Hollywood Reporter magazine. Click here to subscribe.