There’s nothing sweet about Saccharine, but just as it should be gaining traction, nothing terribly coherent about it either. Natalie Erika James throws a bunch of great ideas into her fem-horror riff on body dysmorphia, shame and the tireless quest for physical perfection in a culture obsessed with youthful hotness — following in the path of The Substance and Ryan Murphy’s latest dollop of high-gloss trash, The Beauty. But the storytelling goes haywire, to the point where you’re unsure what the Australian writer-director wants to say, though her game lead, Midori Francis, keeps you watching.

James’ visually stylish film, acquired by IFC and Shudder ahead of its Midnight bow at Sundance, has some originality thanks to a subtle grounding in the Buddhist/Taoist folk tradition of the hungry ghost. But James never commits fully enough to the spiritual/supernatural side to add much dimension to the confused narrative. While the protagonist is Japanese Australian, the movie has a feel closer to Thai horror in atmosphere, if not in intensity or dread.

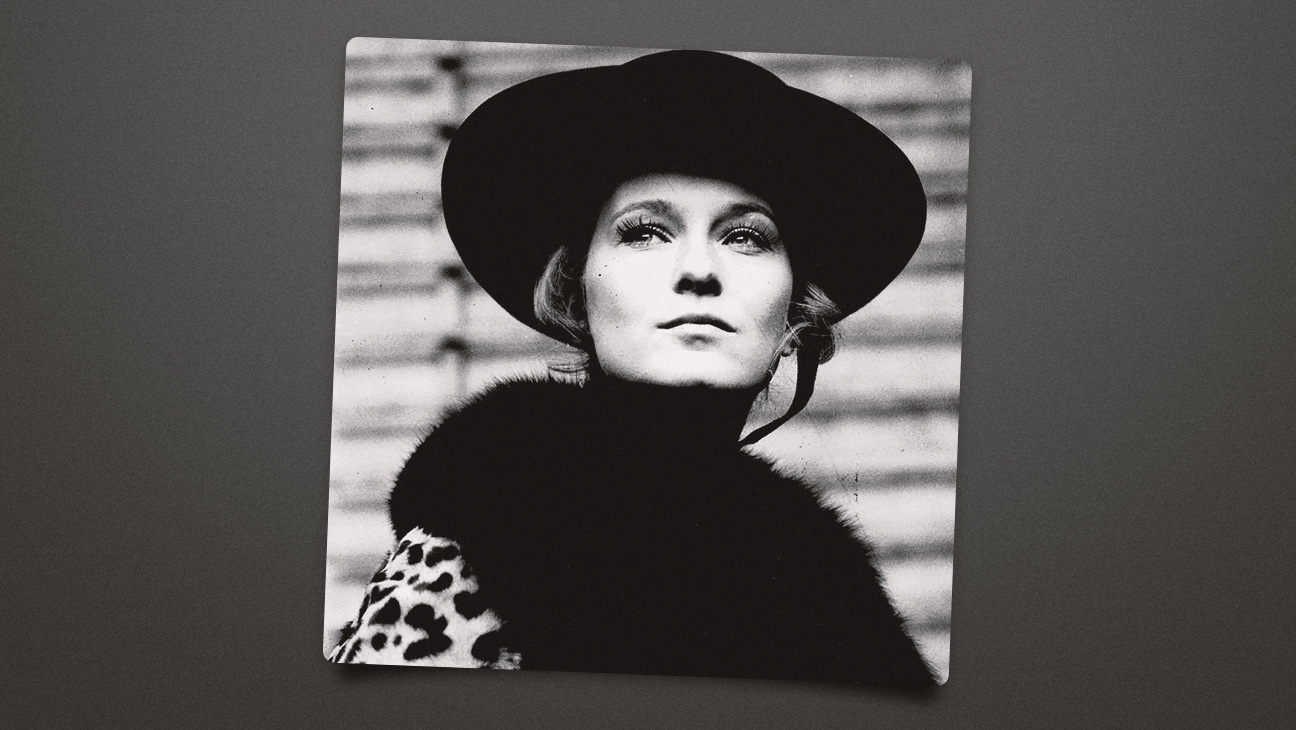

Saccharine

Let them eat cake.

Obsessively recording her observations in a journal and charting her progress on a graph, Melbourne med student Hana (Francis) is determined to get down to her goal weight of 60 kilograms (132 pounds). Her unspoken attraction to toned and confident gym trainer Alanya (Madeleine Madden) might be part of the incentive, given that Hana is queer more in theory than practice. She signs up to be Alanya’s guinea pig in a 12-week fitness program.

While she’s out at a club with her student pals Josie (Danielle Macdonald) and Georgie (Emily Milledge), Hana runs into an old friend, Melissa (Annie Shapero). Hana doesn’t recognize her at first, until it clicks that Melissa is the svelte transformation of the heavy, bullied girl she knew in high school. Telling Hana that the girl from back then is dead, Melissa puts her astonishing weight loss down to a miracle drug she calls “the gray,” giving Hana a few tablets and urging her to try them.

Melissa’s insistence is somewhat questionable since Hana looks like a normal-size young woman by non-Hollywood standards, even with some prosthetic enhancement. But perhaps that’s part of James’ point — that body expectations for women are so unrealistic that many, like Hana, are driven to starvation and self-loathing. Except that with “the gray,” Melissa swears she can eat as much as she wants and not gain weight.

Which appears to be the case when Hana wakes up after a heavy night of clubbing with the messy debris of a large takeout assortment on her bedroom floor and yet somehow feels different. She’s sufficiently intrigued to analyze the pills in the university medical lab, discovering a compound of phosphates and … human ashes. Luckily, she has a cadaver handy, one of several people who donated their bodies to science and are getting cut up in class.

The body assigned to Hana, Josie and their lab teammates is a corpulent woman cruelly nicknamed “Big Bertha.” Hana starts taking home a rib cage here, a few bones there, grinding them up with a mortar and pestle to make her own DIY version of the gray. The compound works, and while her gluttonous binges become increasingly uncontrolled — filmed by James and DP Charlie Sarroff like woozy Francis Bacon images — her weight keeps plummeting. That gets her an admiring comment, an Instagram post and perhaps a flicker of sexual attraction from Alanya.

But homemade meds can come with unexpected side effects — in this case, ghoulish visitations from the hangry Bertha, looking like a cross between Eric Cartman and Nosferatu. Visible only to Hana at first, in convex reflective surfaces like a kettle or the back of a spoon, Bertha does not take kindly to Hana’s attempts to kick the pill habit and start policing her food intake the old-fashioned way.

In one of the funnier episodes, the spectral presence shoots candy bars from Hana’s rucksack across the room at her until she shovels them in her mouth in a rattled semi-trance state. It’s unclear whether Bertha is also enraged by Hana’s weight continuing to drop — she gets down to 45 kilograms (99 pounds) at one point — but girl, we’ve all been there with the body envy.

James’ 2020 debut feature, Relic — a slow-burn chiller about three generations of women tormented by a presence in the family home — worked because the director never allowed her control of the material to slacken, even when the narrative was stretched a bit thin. But Saccharine slips off the rails, especially once Hana convinces Josie that Bertha’s spirit has latched onto her in malevolent ways, growing bigger and stronger all the time.

The always terrific Macdonald (If I Had Legs I’d Kick You) is under-used, and the rebuke of confident, plus-size Josie to Hana for letting fatphobia curb her self-acceptance is a point made too hurriedly to register.

Scenes with Hana’s parents seem intended to shed more light than they actually do, with some psych 101 subtext suggested by the fussing of her birdlike Japanese mother (Showko Showfukutei) and the remoteness of her mostly immobile Australian dad (Robert Taylor), who is steadily eating himself to death. But the parental elements just end up seeming like narrative clutter, with nothing gained by the teasing delayed reveal of Hana’s plus-sized father.

The climactic scenes toy with the blurred lines between hallucination and reality, but the logic falls apart; threads like Hana’s rash decision to undertake a dangerous surgical fix virtually evaporate without much payoff. And at just under two hours, the movie could seriously benefit from cutting some flab.

Saccharine is more polished in its technical aspects than in its storytelling, from the queasy visuals (Sarroff shot Relic, as well as both Smile movies) and sickly lighting to composer Hannah Peel’s eerie synths to some impressively gnarly gore. Ultimately, however, the biggest plus is Francis, whose commitment to the central role is so unfaltering that she makes the script’s rough patches less of a deal-breaker.

James has no lack of talent, but fans of Relic who were hoping this might be a return to form after the mixed-bag Rosemary’s Baby prequel Apartment 7A — either as a juicy serve of Cronenbergian feminism or a movie with something to say about accessible weight-loss meds — will likely be disappointed.