It’s been 26 long years since The Blair Witch Project popularized the found-footage horror genre (which arguably began with 1980’s Cannibal Holocaust). Many other films in the nearly three decades since have claimed their stake in the territory, some successfully, others less so. The latest is Shelby Oaks, a new film that seeks to incorporate found-footage frights with mockumentary trappings and, eventually, regular old narrative filmmaking.

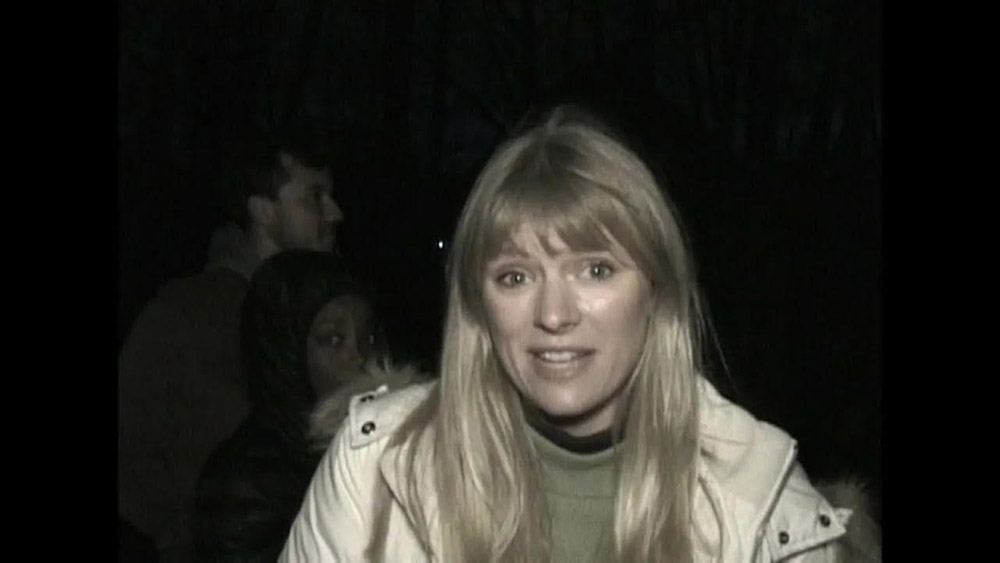

In its opening stretch, Shelby Oaks — written and directed by YouTube movie critic Chris Stuckmann — positions itself as an unsolved-mystery documentary, of the sort that has grown massively popular on streaming services in recent years. A YouTuber who makes supernatural investigation videos, Riley (Sarah Durn), has gone missing while investigating the titular abandoned town, a wooded ruin in rural Ohio. Over a decade later, a documentary crew interviews Riley’s sister, Mia (Camille Sullivan), who is determined to keep up the search.

Shelby Oaks

More horror-movie fancam than something worth stanning.

The details of the case are chilling: The rest of Riley’s ghost-hunter crew was found brutally murdered in a remote cabin; mysterious forms appear fuzzy in the background of the last known footage of Riley. It’s an effectively eerie and intriguing set-up, and Stuckmann does a competent job of simulating the style and cadence of a real documentary. One doesn’t get the impression that anything terribly novel will be shown to us, but Shelby Oaks does, as it begins, promise something sturdy and entertaining, a ghost story cleverly told in modern vernacular — executive produced by revered horror auteur Mike Flanagan, no less.

But then, alas, a gnarly incident occurs while the documentary cameras are rolling and Stuckmann violently shifts gears. The doc conceit falls away, replaced by a shallow attempt at the eerily elegant, off-kilter horror style codified by 2018’s Hereditary. A newly traumatized Mia embarks on a solo quest for answers, delving into the mysterious past of Shelby Oaks and the area surrounding it, which Stuckmann has dubbed Darke County.

One cringes at that name, as it perhaps suggests some ambition to lay the groundwork for a cinematic universe, much as Universal tried to kickstart a Dark Universe franchise with 2017’s dreadful The Mummy. Stuckmann has stated no such plans, but given his long YouTube history as something of a franchise-movie geek, it wouldn’t be all that surprising if there was a hope to further explore the world of Darke County in the future.

Why an audience member would want to return, though, would be an even more vexing mystery than whatever happened to Riley Brennan. As Shelby Oaks moves further away from its original conceit, it grows ever clunkier, ever more derivative. Stuckmann’s dialogue is stilted and generic; his storytelling and world-building even more so. There are some neat little stylistic flourishes that one can appreciate — a gliding camera here, a sudden switch from day to night there — until one realizes that, wait a second, those are things that happened in other recent horror movies. It is increasingly apparent that Shelby Oaks is less the realization of an original vision and more the result of a dedicated film nerd clumsily stitching together things he enjoyed watching in the past.

The influences are obvious, from the contemporary to the more classic. There’s a witchy older woman, played gamely by the great Robin Bartlett, who brings to mind Ann Dowd in Hereditary and Ruth Gordon in Rosemary’s Baby. (And, no fault of Stuckmann’s, Amy Madigan in Weapons.) A creepy prison clanks and moans in the strains of Session 9, the MTV show Fear and myriad video games. Paranormal Activity-style jump scares abound, so much so that they become repetitive, expected, devoid of shock. (It doesn’t help that Stuckmann does way too much indicating of when they will arrive.)

There is a fine line between reverent homage and cheap pastiche; Shelby Oaks largely exists on the latter side. As the film hurries toward its muddled yet turgid conclusion, it becomes glumly apparent that there really wasn’t much of an idea here to begin with. At least, not an idea that at all distinguishes itself amid the film’s onslaught of tropes. The most frightening aspect of Shelby Oaks is the way it suggests what a fully AI movie might one day feel like: a mass of clichés molded into something resembling cinema but falling uncannily short.

It’s been reported that Stuckmann was at least partly inspired by matters from his own life, particularly his sister’s excommunication from the Jehovah’s Witnesses. But whatever personal motivation might lie behind the film is impossible to see in the final product — not in its boilerplate depiction of grief, not in its trite evocations of the occult. The many creaky, half-baked aspects of Shelby Oaks are all the more frustrating when one remembers the film’s solid start, the specific point of view that gradually gives way to Stuckmann’s plodding recitation of hoary horror-movie staples.

Far be it from this critic to suggest that our lowly, sniping cohort dare not transcend to the realm of creative expression. Stuckmann should be applauded for the effort. But he might have more sharply applied some of his critical faculties to his own work. Had he taken that time, he may have found ways to make his film distinct from the many he’s reviewed. Instead, there is Shelby Oaks as it is, a lumbering golem of hyped-up pull quotes about other people’s stuff.