The Vietnam War has been analyzed, litigated and relived in countless books, films and TV shows. Whether we’ve learned a single lesson from the decades-long debacle is another matter. J.M. Harper’s Soul Patrol, a nonfiction feature with scripted elements, doesn’t pretend to offer answers; its first-person exploration of the enlisted man’s experience resounds with big-picture questions about war in general and Vietnam in particular.

Weaving together eloquent visuals with energy and deep feeling, Harper’s second documentary feature, after As We Speak, delves into the memories of a half-dozen soldiers who formed a tight-knit unit tasked with some of the most dangerous missions of the conflict. They were young, some still in their teens, and they were Black soldiers at a time when the “real war,” as one of them calls it — the movement for Black Power and against U.S. militarism — was being waged back home.

Soul Patrol

Loving tribute and dynamic memory piece.

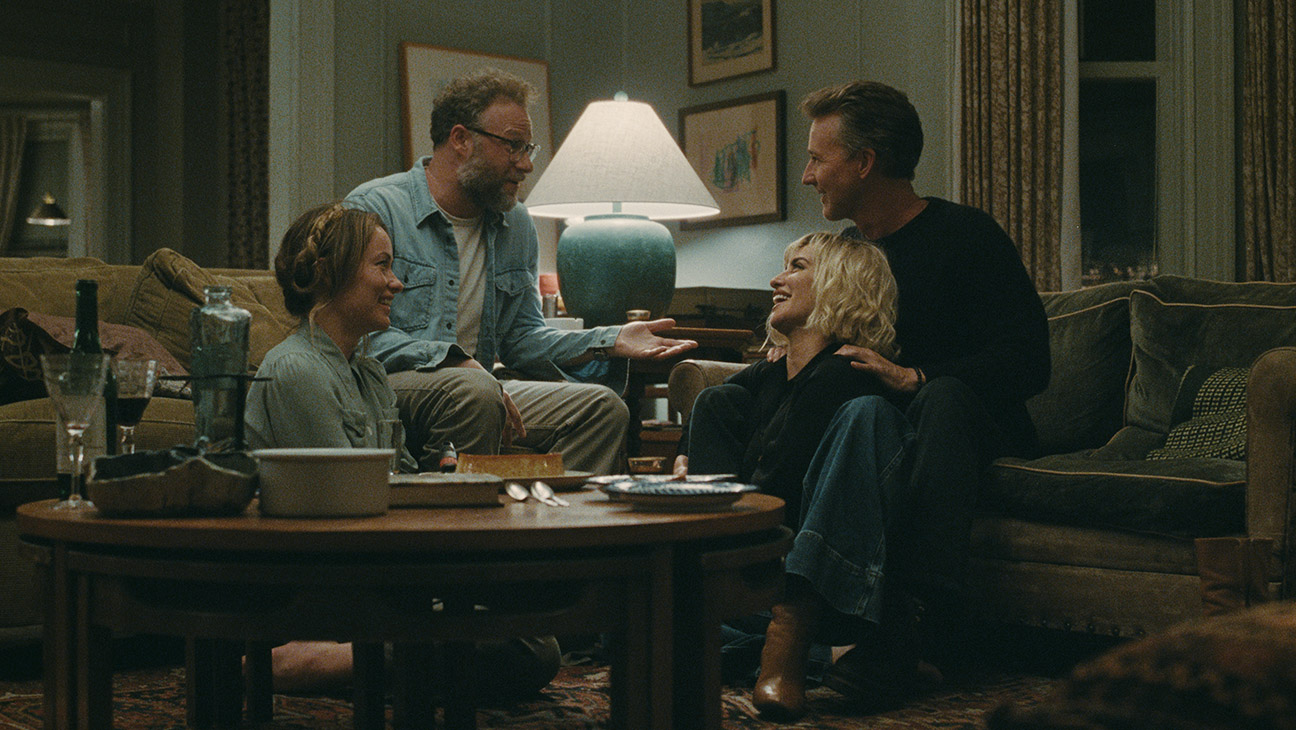

One of these men, Compton native Ed Emanuel, wrote a 2003 memoir from which Soul Patrol takes its name and its inspiration. Emanuel’s goal in writing it, he says, was to free himself from the “demons,” haunting memories of his year in Southeast Asia. He also hoped the book’s publication would help to bring together the tight-knit group he’d been a part of decades earlier — Team 2/6 of Company F, 51st Infantry. It did precisely that, and one of the elements of the film is a black-tie reunion of the surviving team members. Harper also includes a roundtable discussion, the men captured in close-ups in a black-and-white so exquisite it feels like a loving embrace (the cinematographer is Logan Triplett). Their wives receive similar treatment in a brief convo about the emotional fallout of the war.

It was Sgt. Jerry Brock, the team leader who turned out to be someone Emanuel knew from Compton, who put together the first all-Black special ops team in Vietnam. (Brock died before the group’s reunion.) The team was a long-range reconnaissance patrol, or LRRP (pronounced “lurp”), a six-man unit trained for five-day jungle forays deep behind enemy lines — “more than a SEAL, more than a Green Beret,” Emanuel says. They were dubbed Soul Patrol by a colonel — not a problem for some, but offensive to Emanuel (“I wasn’t a soul brother, I was a soldier”).

Beyond Emanuel’s authorship and another man’s mental-health struggles, the only biographical details in the doc concern the men’s youth. Thad Givens came from a military family. Lawton Mackey Jr. was a fieldworker in South Carolina earning $3 a day and the youngest of the crew; he’d enlisted at 17, and regretted it upon arriving in the quagmire of Vietnam: “I forged my mama’s signature to get in this damn mess.” Norman Reid, from the Bronx, had crossed a drug dealer and saw the Army as a relatively safe alternative to facing the consequences, while Emerson Branch, in trouble with the law, took the military option rather than be transferred from jail to the penitentiary.

At the heart of the documentary is the conflict between the men’s pride in their skill, bravery and devotion and their doubts over the purported reasons for the war. Their tours began around the time of Martin Luther King’s murder, and one recalls learning of Robert Kennedy’s assassination on the jet to Vietnam. The growing fervor of the antiwar and Black Power movements is encapsulated here in footage of leaders including Stokely Carmichael, Harry Belafonte and Bobby Seale, and searing audio of King: “As I ponder the madness of Vietnam …”

Against this passionate backdrop, it’s jolting to hear one of the former soldiers use the phrase “give back to America” and speak of the possibility of changing the system from within. Jolting and heartbreaking, given that Black soldiers’ numbers and casualty rates were disproportionately high compared with their stateside population, yet they were barely mentioned in the constant media coverage of the war.

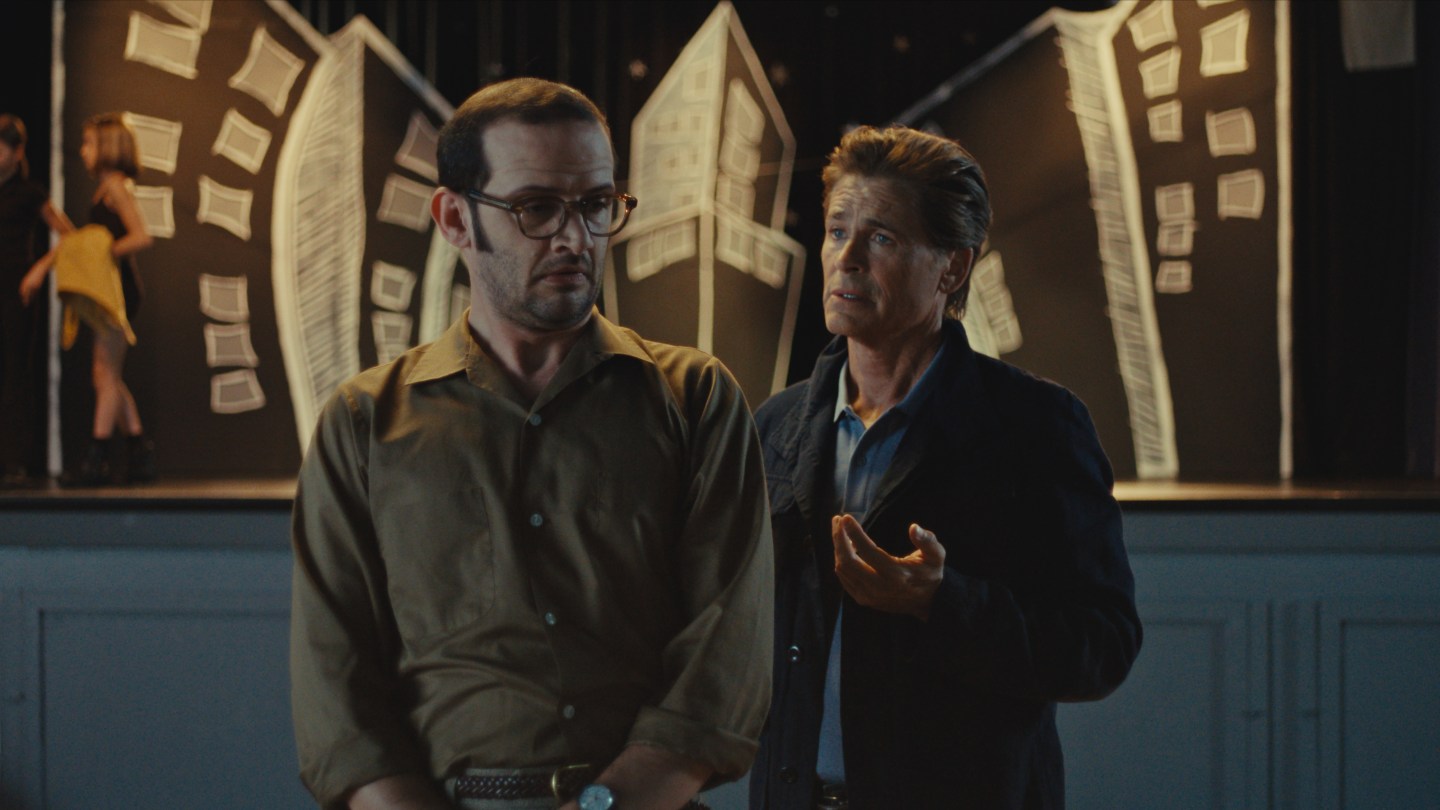

Actors portray the LRRP team in sequences that Harper calls “adaptations.” These include wartime reenactments that are notable for the way they capture the boredom, confusion, chaos and terror of the men’s missions, some of which they were sent into knowing they weren’t expected to survive. But the writer-director takes the doc to another level with adaptations that place the young soldiers, in battle fatigues and brandishing arms, in the aisles of a contemporary supermarket, speaking lines from Nietzsche.

At first this conceit, entwining the otherworldly intensity of war with the everyday, feels self-conscious. But the poetic leaps gather emotional force as the film proceeds. And they’re a thoughtful, affecting complement to the Super 8 footage that Harper incorporates, shot by American soldiers in their off-hours on base: evocative images of young friends hanging out between impossible assignments. Working with the editing team of Byron Leon, Niles Howard and Gabriela Tessitore, Harper, who began his career as an editor, moves among the disparate elements of his film with fluency.

Soul Patrol offers an essential historical chronicle, and one that reverberates now, when there’s not even a pretense that compassion and nonviolence are political ideals. It gives voice to Emanuel and his comrades, who reveal that they didn’t talk about Vietnam for years. Given the mood of the country, it was hardly a heroes’ welcome that they received upon returning home. They speak of the ensuing isolation, silence, rage and mistrust. “We don’t allow ourselves to release the pain,” Givens says, half a century later, of the combat experience.

But some of them vividly recall letting off steam during R&R in Bangkok. Emanuel, whose cousin had recently been killed in combat and who was bent on revenge against the “enemy,” had a revelation during those days away from the front. He was meeting working-class people “just like me,” he says, and revenge suddenly felt hollow. In this film about war, told by those who survived it, it’s war’s futility that rings loud and clear.