Director Mahamat-Saleh Haroun is known for hard-hitting, evocative dramas set in his native Chad, a country that was embroiled in sectarian conflict for decades. Movies like Dry Season, A Screaming Man (which won Cannes’ Jury Prize in 2011) and Grigris followed men in various states of turmoil, beset by violence and other hardships in the Sub-Saharan desert. Along with his unflinching documentary on the humanitarian crimes committed by Chadian dictator Hissen Habre, Haroun’s films form an uncompromising body of work that’s definitely bleak, but can also be rather luminous.

His previous feature, Lingui, The Sacred Bonds, marked a change of direction for the auteur, who focused on female characters for the first time and offered a more hopeful vibe than before. He continues this streak with Soumsoum, the Night of the Stars (Soumsoum, la nuit des astres), a modern-day fable of adolescence and resilience that plays, at times, like a classic teen horror flick — minus the jump scares but with similar twists and motifs.

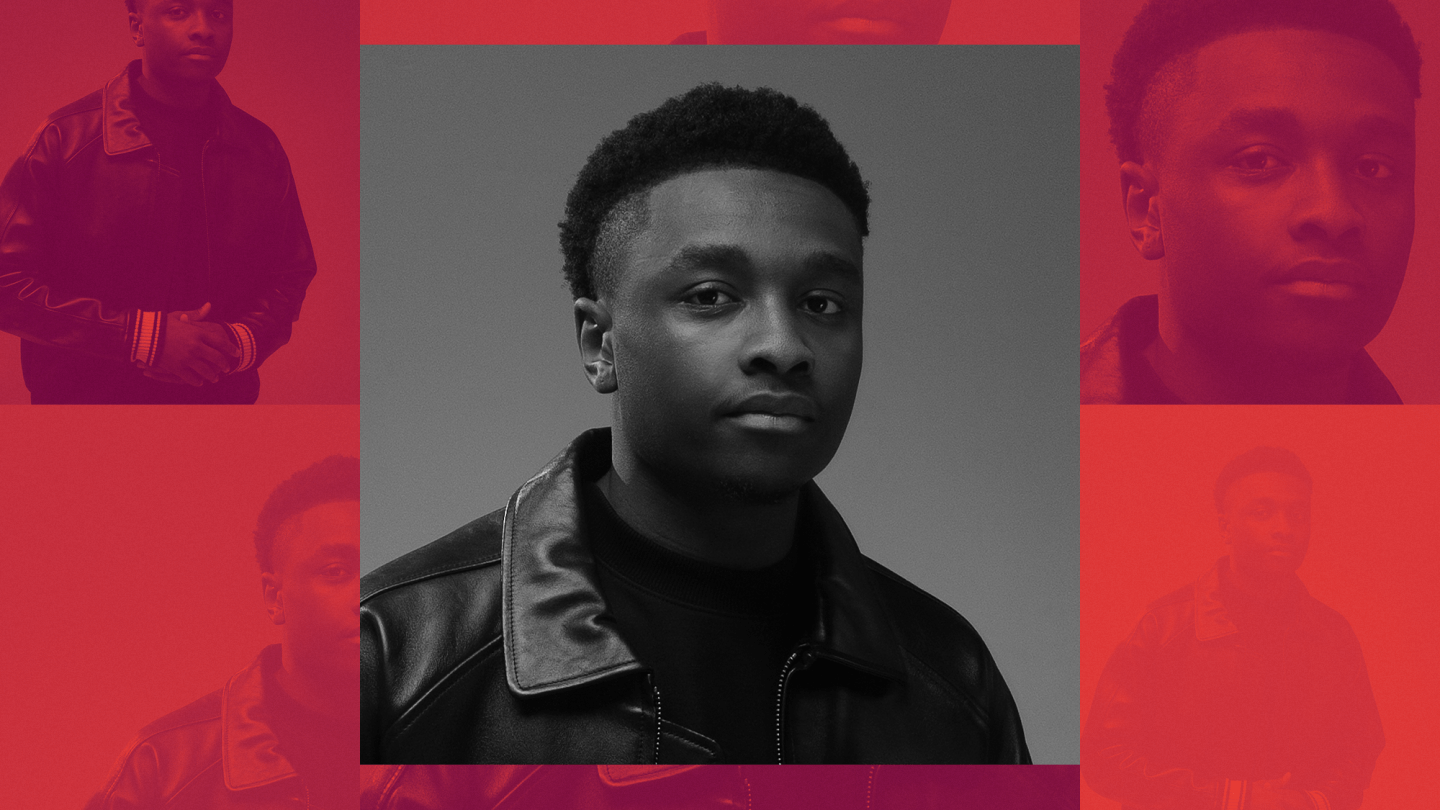

Soumsoum, the Night of the Stars

Languid, spooky and stunningly shot.

Not that this Berlin competition premiere will have viewers leaping from their seats. Haroun’s austere style and languid pacing are strictly for the art house. But there are some memorable moments in this rich and strange desert tale, many of them set against the breathtaking Ennedi Plateau in Northeast Chad where much of the film was lensed.

Indeed, the incredible landscapes in Soumsoum are nearly characters unto themselves, resembling a cross between the Monument Valley of Hollywood Westerns and planet Arrakis from Dune. They provide the perfect setting for the otherworldly happenings of Haroun’s slow-burn fantasy flick, which combines a tale of adolescent angst with fits of sorcery, blood and other freaky things.

Written with French novelist Laurent Gaudé (Dog 51), the story follows 17-year-old high school student Kellou (Maïmouna Maiwama), who lives in a village that was recently destroyed by floods (heard via sound effects over the opening credits). Rebellious and testy, Kellou shares a tiny home with her father (Ériq Ebouaney) and stepmother (Brigitte Tchanégué), but spends as much time as possible frolicking with her boyfriend (Christ Assidjim Mbaihornom) in the nearby canyons.

In other words, Kellou is an average teenage girl. Except, that is, for the fact that she sometimes has visions of death, zombies and other horrific things that may either be flashbacks to the past or prophecies of the future. “I don’t think I’m normal,” she tells her dad, who hardly listens to her. But when Kellou runs into a mysterious woman named Aya (Achouackh Abakar Souleymane), who’s shunned by the other villagers, things start to make sense. Not a lot of sense, but enough to mark a radical change in the girl’s life, allowing her to face up to a past that’s been weighing her down for some time.

It’s unclear if Haroun is a fan of movies like Carrie or The Exorcist, both of which come to mind while watching Soumsoum. Whatever his inspiration, the director is after something a little different here, using elements of the horror genre, along with African folklore, to explore Kellou’s trauma (we learn she was “born in blood,” meaning her mother died during childbirth) as well as that of her father, an immigrant outcast with a dark backstory of his own.

These plot points appear in an otherwise tepid narrative that doesn’t exactly grab you by the throat, even if some of Kellou’s visions are mildly spooky. They’re also visually imposing, especially when the director and regular DP Mathieu Giombini head out to the desert to frame the teenager against massive rock formations that look like giants from another planet — including one sequence in which Haroun employs CGI to bring the landscape to life. There’s always been a surreal side to the auteur’s work, but he chases after it more in Soumsoum than ever before.

This doesn’t necessarily make the film an easy watch, especially when the narrative tension gets hampered by a lethargic rhythm and performances keeping us emotionally at bay. Newcomer Maiwama is nonetheless convincing as a girl trying to make sense of what’s happening both around her and within her warped mind, turning Kellou’s pariah status into a weapon that could ultimately save her.

If Haroun manages to find a rather painless antidote to his heroine’s crazy predicament, subverting the genre’s usual blood-soaked finale for something simpler, he at least finds a meaningful one. His latest movie may feel like a detour from his previous work, but it’s yet another tale told in a land haunted by death.