If you ever looked at the ageless face of Isabelle Huppert onscreen — the alabaster skin, the enigmatic smile, the eyes that seem to have a default setting of disdainful superiority — and thought all that was missing were a glistening pair of fangs and a tiny trickle of blood from the corner of her mouth, this is the movie for you. Likewise, if you ever wondered what kind of bizarro Mittel European mutant baby would result from the marriage of Robert Eggers’ Nosferatu and Wes Anderson’s The Grand Budapest Hotel. Perhaps it would look something like Ulrike Ottinger’s Viennese waltz of grotesquerie, The Blood Countess (Die Blutgräfin).

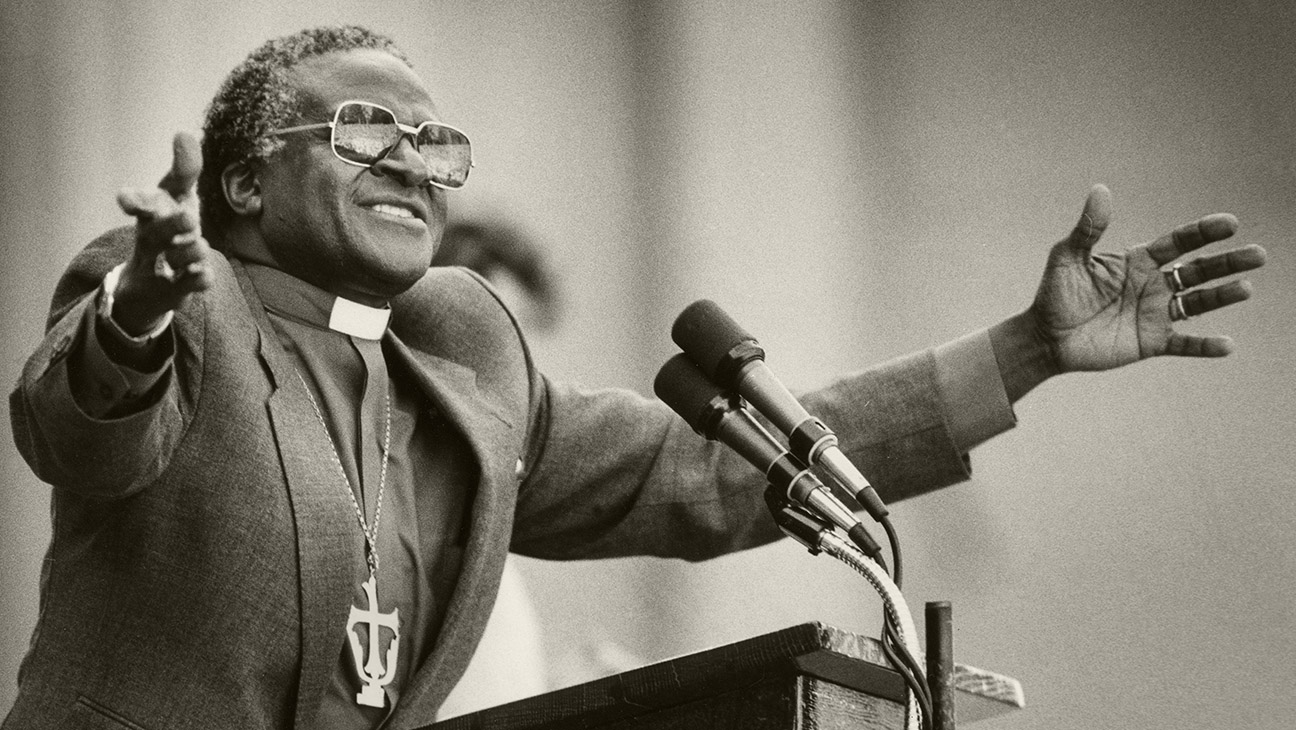

A painter and photographer as well as a cult filmmaker, Ottinger understands the power of a striking image. She opens with a mesmerizing sequence in which a barge upholstered in plush vermillion velvet cruises ever so slowly through an underground cave system and grotto in Vienna. Standing with regal stillness on the front of the boat, like a carved figurehead on a prow, is Huppert as Countess Elizabeth, a commanding vision in blood-red gown, gloves and jewels to match her copper-colored hair. She alights with a dramatic billowing cape behind her and steps out into the modern-day Austrian capital.

The Blood Countess

If only everyone else were on Huppert’s level.

Elizabeth has barely hit town when she exchanges a come-hither glance with a pretty young woman whose creamy neck is soon punctured by teeth marks. The life drains from her body on the floor of a ladies’ restroom. But the glamorous noblewoman has not emerged from decades of slumber in a glass coffin at the Kremlin just to feast. She is troubled by talk of a legendary book that can turn vampires back into mortals should they shed tears on its pages.

That’s probably the first clue that the screenplay by Ottinger — with additional dialogue by Nobel laureate Elfriede Jelinek, no less — will not be overly worried about the finer points of plot logic. Weeping vampires are relatively rare and yet Elizabeth and the devoted servant with whom she’s reunited, Hermione (Birgit Minichmayr, looking like a demonic Louise Brooks), seem to think this ancient volume poses a major threat to the existence of their kind.

Mostly, the book serves to set them on a daffy quest through Vienna’s historical sites and libraries in order to find and destroy it. But before they get started on that there’s a vampire ball to attend, at which the Countess makes her grand entrance while being exalted as “a woman untouched by virtue.” (Love that for Huppert.) There’s a buffet of human corpses, a vampire string quartet and a soprano celebrating the qualities of Viennese blood. Then there’s the real entertainment. A row of handsome young men in formalwear is ushered onto the stage and seated, followed by the same number of women who are blindfolded and given straight razors to shave the gentlemen before slitting their throats. “Dinner is served!”

This probably sounds a lot more entertaining than it is. I could watch Huppert queening it up until the cows come home, and it’s likely she hasn’t had this much self-satirizing fun since her hilarious Call My Agent! episode. But Ottinger doesn’t do much with her beyond putting her in a series of bejeweled outfits (designer Jorge Jara Guarda did the fabulous costumes), untethering her and letting her float majestically above a whole bunch of increasingly tiresome people on her tail, all of them mugging up a storm.

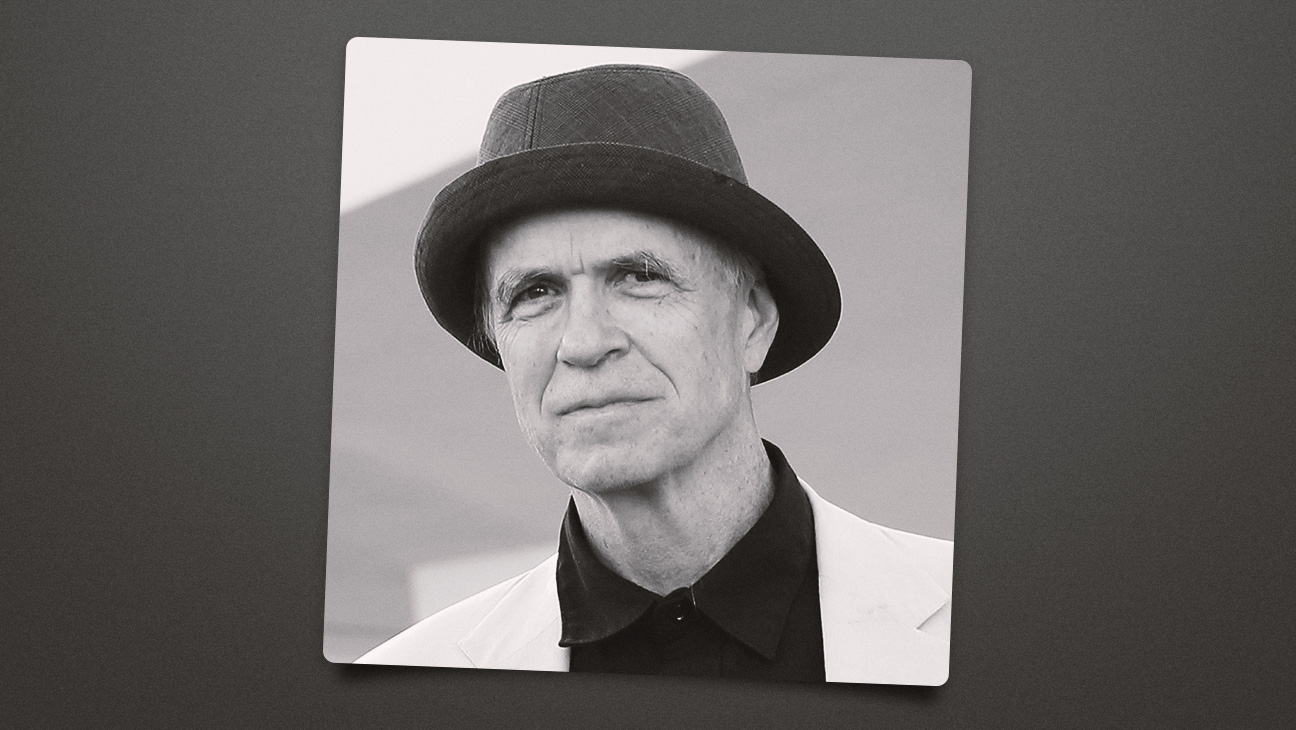

They include one of the neo-Báthorys from Transylvania, Baron Rudi Bubi (Thomas Schubert, so good in Christian Petzold’s Afire), a dandy in green who has shamed the family by going vegetarian; his psychotherapist Theobold Tandem (Lars Eidinger); dithering vampirologists Theobastus Bombastus (André Jung) and Nepomuk Afterbite (Marco Lorenzini); and two cops, Chief Inspector Unbelief (Karl Markovics) and Assistant Guido Doppler (Felix Oitzinger). The names alone should give an accurate indication of the unrelenting level of quirk, with everyone dialing up the eccentricities to 11.

It all becomes too self-consciously arch to be clever. There’s an additional quest element in Elizabeth seeking documents about her family lineage to fight her erasure from the history books. But that doesn’t add much beyond three crusty Báthory ancestors carousing drunkenly in their coffins. Super-annoying.

There are stops at a monastery in Leipzig, its catacombs decorated with human skulls and bones, policed by a Mother Superior who’s handy with a crucifix; a Funeral Museum with a Café Mortuary; a queer cabaret, where Austria’s Conchita Wurst (Tom Neuwirth) performs “Rise Like a Phoenix,” the power ballad that won the Eurovision Song Contest; and a final act back in Vienna at the Prater, with scenes on the historic Wiener Riesenrad, the giant Ferris wheel that inevitably brings up associations with noir classic The Third Man.

Queer feminist filmmaker Ottinger’s work is known for its rejection of conventional linear narratives, but would a little coherence be too much to ask? The Blood Countess devolves into such haphazard, nonsensical plotting (with a resolution far more rushed than satisfying) that it’s a challenge to stay with it for the protracted two-hour duration.

At least there’s Huppert in gloriously aloof form, plus the overripe lusciousness of Martin Gschlacht’s cinematography; with an edible and/or a cocktail or three, that might be enough.

There have been numerous films made about Elizabeth Báthory, who was convicted of torturing and murdering hundreds of women between 1590 and 1610; according to legend, she bathed in their blood to maintain her youthful looks. As sublime as Huppert is, if I’m in the mood for a campy retelling of the Báthory story, I’ll stick with the trashtastic 1971 Hammer horror production with Ingrid Pitt as the busty bloodsucker, Countess Dracula.