In June 2019, Baltimore’s Conviction Integrity Unit received long-suppressed material from a notorious murder case, exculpatory evidence so clear that the unit’s director made the matter a priority, and the men who’d been convicted of the crime were released from prison in time for Thanksgiving. They were known as the Harlem Park Three, after the junior high where the fatal shooting took place, and they’d been behind bars for 36 years, sentenced to life as teenagers for something they had nothing to do with.

Dawn Porter’s gripping documentary takes a measured, multipronged approach as it examines the nightmarish miscarriage of justice, the longed-for and extraordinary resolution, and the possibly unhealable wounds for almost everyone involved: the exonerated, the witnesses who were pressured by police to corroborate a concocted story, and the community where they all felt safe and protected until the day in November 1983 when a ninth-grader was killed for his jacket.

When a Witness Recants

Wrenching, illuminating and full of heart.

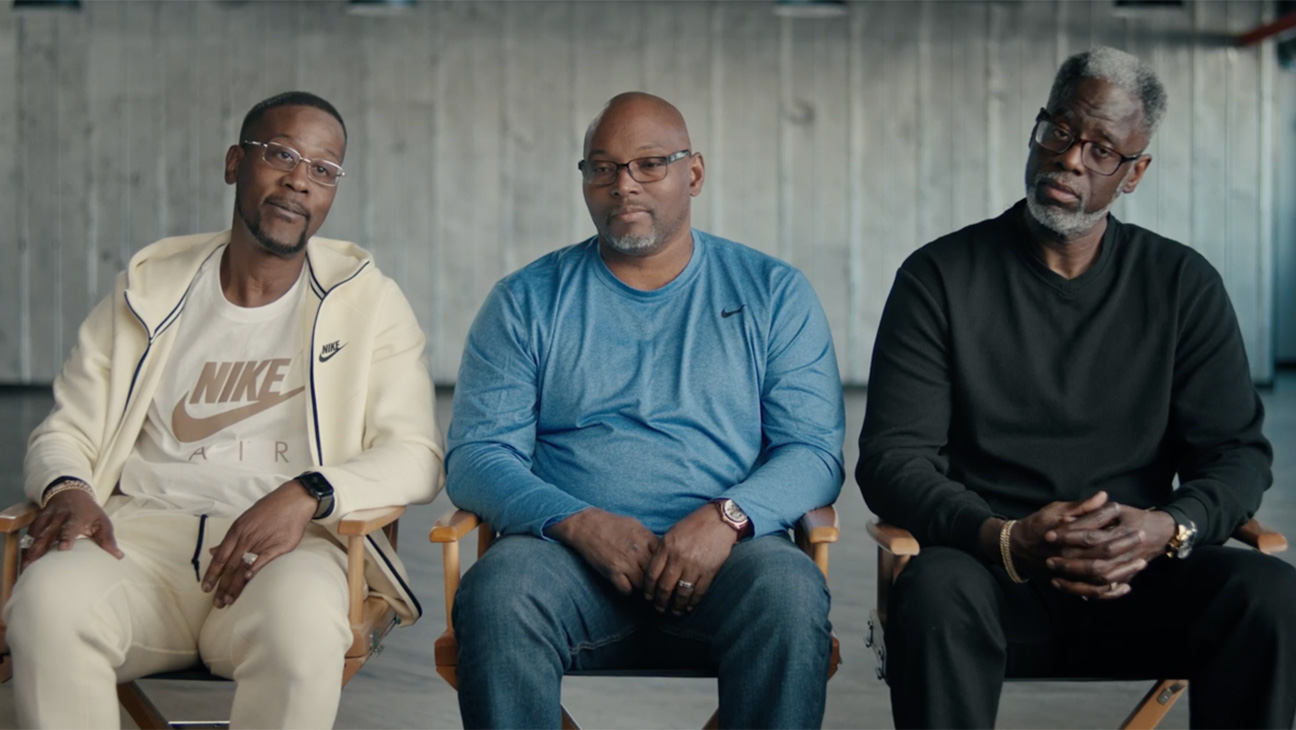

Based on a New Yorker article by Jennifer Gonnerman, When a Witness Recants interweaves new interviews, deposition videos and TV news reports to examine an infamous case of wrongful conviction. Ransom Watkins, Andrew Stewart and Alfred Chestnut, the lifelong friends who survived the unspeakable ordeal, are compelling participants in the film, as is Ron Bishop, the slightly younger neighbor who was long haunted by the false testimony he provided against them under duress. Author Ta-Nehisi Coates, an 8-year-old in West Baltimore at the time of the murder, offers piercing commentary on the impact of both the initial crime and the succeeding one, the grievously unjust trial that put three kids in the penitentiary.

To depict some of the events described by interviewees, Porter (The Lady Bird Diaries) employs expressive black-and-white illustrations by comic book artist Dawud Anyabwile (Brotherman) that capture a kid’s-eye-view of the unfolding horror. They also impart a fitting sense of heroism in the face of the ungodly.

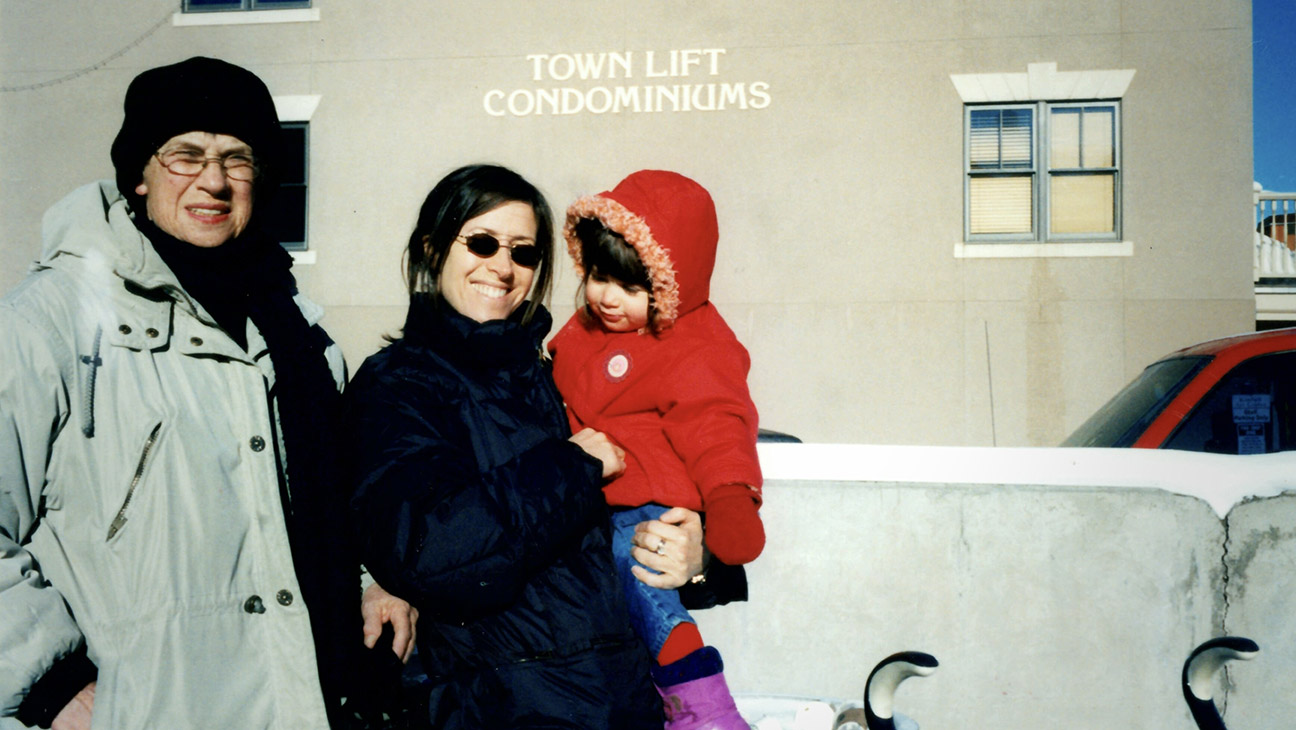

Watkins, Stewart and Chestnut were 16-year-old graduates of Harlem Park Junior High who happened to have visited their old school on the Friday when 14-year-old DeWitt Duckett was shot dead for his blue satin Georgetown jacket. They knew Duckett, and also his classmates Bishop and Edward Capers, who were with him when he was attacked by an older boy. Everyone knew everyone in West Baltimore, a tight-knit, predominantly Black neighborhood. “It was the village raising us and loving us,” Stewart says, recalling a lively and idyllic childhood and a strong sense of community. Coates concurs. “This case,” he says of Duckett’s murder, “is the break.”

Community spirit gave way to suspicion and fear. A couple of excerpted newscasts quote a chilling statistic about Harlem Park Junior High: It was an “87-door school,” and none of those doors was kept locked during the day. Kids were scared, parents were worried, and the shocking crime instantly became a high-profile case, meaning, of course, that there was high pressure to convict.

In the fast-moving investigation, teens were questioned without their parents or an attorney present. Moving beyond the scope of Gonnerman’s 2021 article, Porter’s film includes excerpts from 2022 depositions for the exonerated men’s federal lawsuit against the Baltimore Police Department, which resulted in a landmark settlement. The deposition videos reveal mind-boggling nonanswers by the BPD’s lead investigator on the case, Donald Kincaid. Neither he nor the trial judge, Robert Bell, spoke with the filmmaker, and prosecutor Jonathan Shoup, who insisted on sealing documents that even the judge didn’t read, died in 2016.

How Kincaid became convinced that Watkins, Stewart and Chestnut were responsible for Duckett’s death is a mystery. But Bishop and Capers (seen in a deposition interview from jail, where he’s serving a 28-year sentence for unrelated crimes) both recall his threats of physical violence and imprisonment if they didn’t get on board with the official story. They insisted there was one shooter, and it wasn’t any of the three boys they were pressured to identify. “The more truth I bring out,” Capers says, “the worse it got. So I just shut down.”

“They put a lot of effort into hiding the evidence.” Chestnut’s attorney, Barry Diamond, says of the prosecution team. Despite the witnesses’ vague and contradictory testimony, the jury convicted the defendants after less than three hours of deliberation. But the incarcerated trio never gave up. They refused to play the probation game and express remorse for a crime they didn’t commit. After three and a half decades, Chestnut’s dogged pursuit of the case’s police reports paid off. And Bishop’s formal recantation helped to fast-track the overturning of the convictions.

The New Yorker article ends with the Harlem Park Three receiving a letter of apology from Bishop and accepting his words with wholehearted gratitude and respect. The idea of an in-person meeting is suggested, and several years later, Porter arranges it. Perhaps it’s the passage of time, the pointedly neutral setting or the presence of cameras, but nerves seem to get the better of Bishop, and, in response, the pent-up hurt and anger of Watkins, Stewart and Chestnut find urgent expression. What transpires is no kumbaya moment. But who could expect such a neat and simple thing, Porter’s film asks, after all this?